Recovery or Renewal? Time for an economic rethink

A recent study of long-term fluctuations in economic growth published in Nature Scientific Reports suggests both danger and opportunity in the emerging debate about post Covid-19 economic recovery. In this blog, Craig D. Rye and Tim Jackson outline their findings.

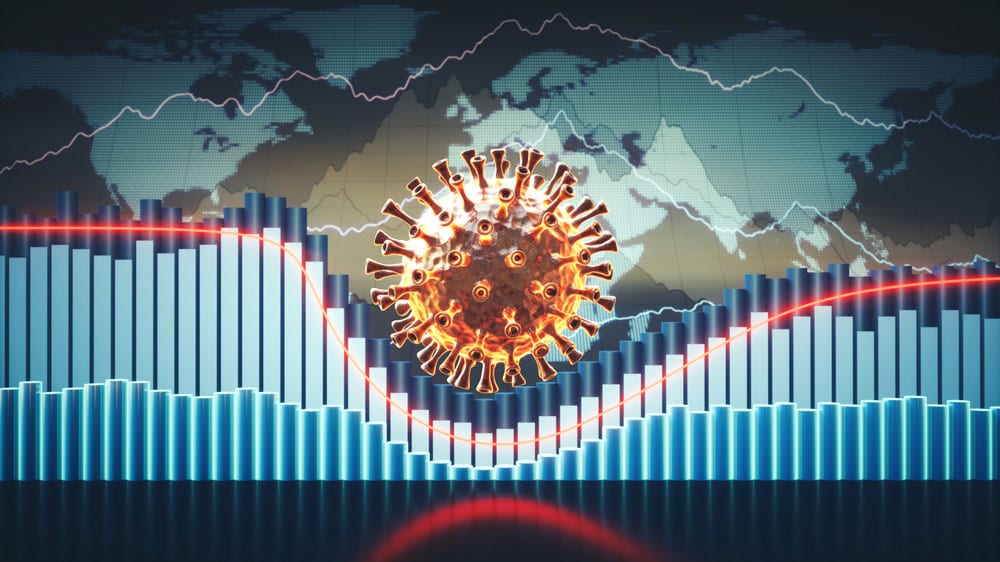

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects the global economy to contract by 5% this year alone, making it the largest downturn since the Great Depression in the 1930s. Advanced economies are likely to see a 10% decline in output and even the emerging economies of south-east Asia are unlikely to escape a recession.

Unprecedented though this is in the modern era, its real impact lies in the wider tapestry within which this uncomfortable economic portrait is drawn. Rates of economic growth across the OECD have been in decline since the 1970s, a phenomenon known as ‘secular stagnation’. The average growth in GDP per capita across the rich economies fell from over 4% in the mid-1960s to little more than 1% in the pre-pandemic years. The decline is related to an underlying stagnation in labour productivity growth.

In a recent study, published in Nature Scientific Reports, we’ve been exploring an even longer story about the ups and downs of economic growth and recession. Critical Slowing Down (CSD) theory is most commonly used to understand the oscillations (waves) in physical systems. In our study, we used the same techniques to analyse long-term trends in the gross domestic product (GDP) in datasets from as far back as the 1820s.

Imagine a pendulum or swing which is held in its equilibrium position by gravity. A push or a shove in one direction or another will shift the pendulum away from the central position or a random gust of wind might move the swing, but gravity pulls it back again. The stronger the force of gravity, the harder it is for the pendulum to swing, so the oscillations around the equilibrium are tightly constrained. If gravity were to get weaker and weaker—or the pendulum were taken into space, for example—the swings would be wilder and less easily constrained.

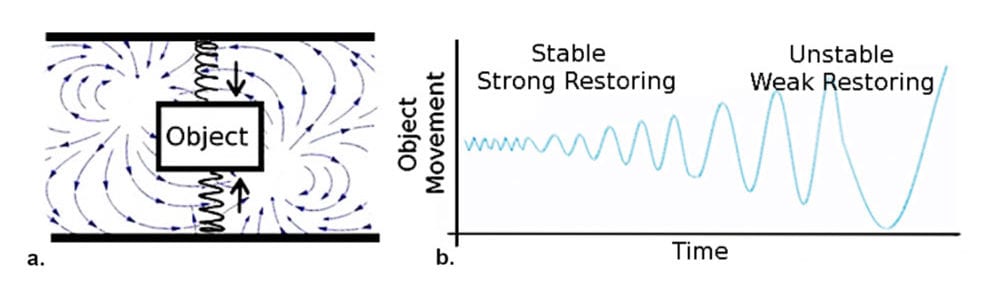

A similar story can be told about the oscillations in an object tethered between two springs (Figure 1). As the springs weaken the oscillations get slower and larger. That’s Critical Slowing Down.

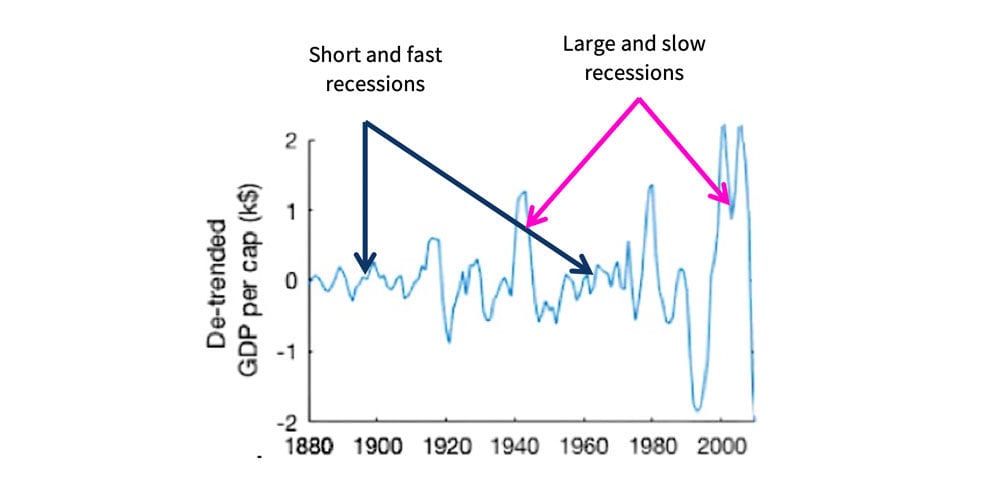

Our recent study has applied the same ideas to the oscillations (waves) in economic output, also known as recession cycles (or business cycles). Put simply, our analysis suggests that the ‘restoring forces’ in economic cycles have changed over time. There are periods in history where recessions are frequent but small with fast recoveries to the equilibrium growth rate (Figure 2). But there are also periods in history where recessions are less frequent, but large and with much slow recoveries. The broad pattern is consistent amongst the high GDP nations over the past 100 years. We are currently in a period of high ‘instability’ with large but less frequent recessions.

This is the backdrop against which the Covid-19 pandemic is playing out. The impact of a large deep shock to the economic system will be profound. The word ‘critical’ in CSD theory suggests that at a certain point the system will become unstable. When a constrained, dynamic system is close to breaking point, its ability to recover decreases. Fluctuations around the system equilibrium become deeper and more pronounced because its internal stabilisation forces have weakened.

There is no easy way back to equilibrium growth because the restoring forces in the economy were already weakened, for reasons that we don’t entirely understand. Shifts in economic structure, unstable financial markets, unsustainable debt: all these things have been suggested as possible reasons for the ‘secular stagnation’ of advanced economies. The one-off burst of high labour productivity growth may only have been possible at all because of the unsustainable use of fossil fuels.

But none of these conditions make the prospects for economic recovery from the pandemic straightforward. A short sharp return to high economic growth is very unlikely, if the statistical analysis from the long-term trends is correct. Placing the economy on hold to prevent unfathomable human tragedy from the Covid-19 pandemic was the right decision. Trying to force our way back to economic growth now would be the wrong one. A post-growth world is now even more likely to be the ‘new normal’. At least for the advanced economies.

On the other hand, there is a curious corollary to this lesson from physics. A system with weak restoring forces is more easily guided into a new equilibrium. With appropriate policy, we have a unique opportunity to refashion and reshape the economic models that have been failing us for decades. The challenge is enormous. But so is the prize. Our analysis suggests that we are better placed than ever to make the transition to a resilient, sustainable economic system which protects the health of people and planet.

Links

- Rye, C and T Jackson 2020. Using critical slowing down indicators to understand economic growth rate variability and secular stagnation. Nature Scientific Reports. Online at: www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-66996-6

- Global economic stability could be difficult to recover in the wake of the Covid-19 | University of Surrey Press Release, 26 June 2020

About the authors

Craig Rye is a systems analysis researcher, currently based at Columbia University (New York). He is holding a Ph.D in Ocean Physics and a BSc in Environmental Sciences. He is working within our systems analysis theme.

Tim Jackson is the Director of CUSP. His vision for CUSP builds on thirty years of multi-disciplinary research on sustainability and decades of policy experience, in particular his work as Economics Commissioner on the UK Sustainable Development Commission. Tim is the author of Prosperity Without Growth, recently published in a substantially revised and updated 2nd edition.