Situated Understandings of the Good Life

Our pursuit of prosperity is shaped by material circumstances and situated within social and physical environments. As part of our work programme, we have been speaking to people in different places and neighbourhoods to explore how visions of the ‘good life’ and ‘good work’ emerge in the context of their everyday lives. In this blog, Sue Venn, Kate Burningham and Tim Jackson are summarising the early findings.

Blog by SUE VENN, KATE BURNINGHAM and TIM JACKSON

Would someone living in a small market town in a national park have the same perception of a good life as someone living in a busy commuter town or a post-industrial city? This was the question we considered in our study “Situated Understandings of the Good Life”, that is what do people of different ages, ethnicities, backgrounds and socio-economic circumstances consider necessary for a ‘good life’ where they live. We wanted to see where visions of a good life may diverge, but also where there may be elements of consensus, and to see the potential in this for securing ‘a good life’ which is socially just.

The reality was that a ‘good life’ is less about the need for material possessions and aspirations for having more than about feeling a part of where people live and their community. It was also about having enough – whether that be work, decent housing, green spaces, or prospects for future generations. “I have always thought, you know, [a good life is] about family, about where I live and things like that. Just little things”

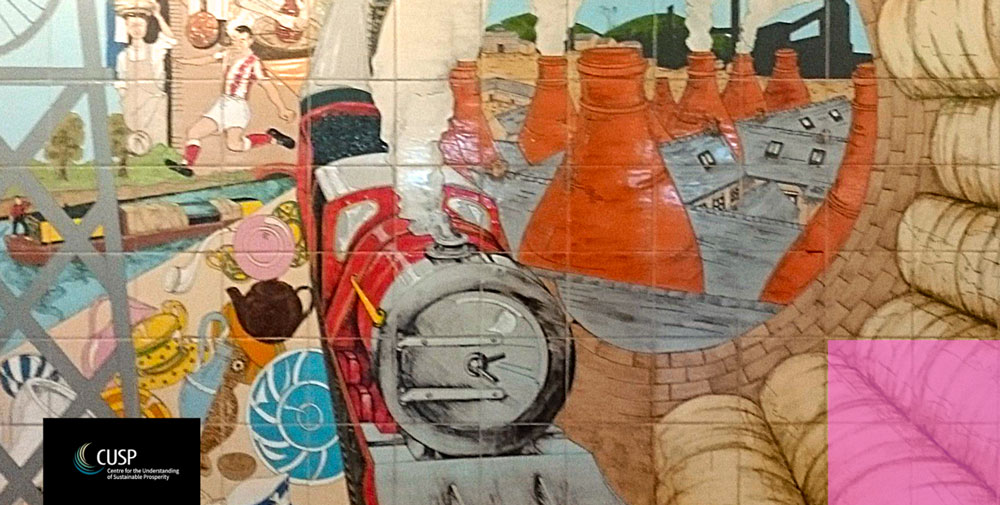

The three locations we chose were Stoke-on-Trent, Woking and Hay-on-Wye. Stoke-on-Trent is regarded as a post-industrial city with areas of disadvantage, but a rich cultural heritage; Hay-on-Wye is known for being a small market town on the Welsh/English border with a strong local history, but is also known as a destination for people wishing to find the good life; and Woking is seen as an affluent commuter town, which also has areas of social disadvantage.

We spent time getting to know these places and the people who live there, asking them to tell us about their everyday lives including where they work or study, how they get around, the local environment, leisure time and ways of consuming, and asked them to reflect on where they live, what they like about it and what they would change. The final question we asked was “what for you is a good life?”.

Our approach was always to place the people and their accounts at the heart of our research, and to share our work with them, so we concluded our study of each place by running workshops where we invited local people to hear a summary of our findings and comment on how they relate to their own experiences. We also asked them to consider how these findings and their own knowledge of where they live could be used to positively shape their town’s future. A report of each workshop was produced and shared widely.

There are clear differences in each of these locations which of course have their own unique historical context, geographical setting, economic capabilities, and social milieu. The high cost of living, and housing in Woking was a concern for all residents; unemployment was a major issue in Stoke, particularly for young people, and public transport in and out of Hay-on-Wye was thought to be both expensive and lacking. Yet there were also shared ideas of what it means to live well which hold promise when considering how inclusive visions of a good life may be achieved.

1. Identity and Belonging: “I’m proud to be from …”

From the industrial heritage of the potteries in Stoke on Trent, (“we are the Potters”), to the eclectic mix of residents of Hay (“there’s a broad range of people that live here”), and the vibrancy of Woking (“the town has been rejuvenated”), local people were keen to share the good things about where they live and their strong sense of local identity. These shared positive aspects of a place were important for residents, not only in creating mutual feelings of place attachment but also in defending the reputation of their towns from ‘outsiders’ who may see it differently. The challenge was how to retain a sense of a shared identity as places undergo constant change. In Stoke-on-Trent and Woking ongoing regeneration is changing both the look and feel of the town centres and surrounding urban areas. Residents in Woking were unsure about their town’s future identity, how it would change, who would benefit from those changes, and even who those changes are actually for.

Our time in Stoke-on-Trent coincided with the Brexit vote, and Stoke became the brunt of negative media interest, even being called “The Brexit Capital of Britain” (Domokos 2018). Yet in so doing, the media failed to take account of how harmful representations actually strengthened local identity – “we call it a shithole, but nobody else can”. Residents of Hay-on-Wye have had to adjust from being a market town with a strong agricultural heritage and economy to also being a tourist attraction which hosts regular festivals. The regular influx of tourists was challenging for long term local residents whose way of life both depends on seasonal and transitory visitors for a living, but is also disrupted by them.

2. Community

Our participants shared numerous narratives and definitions of ‘community’. From the importance of established community groups with places for meeting up, to the broader concept of ‘community spirit’ people talked of how their own communities are invaluable for supporting each other, bringing people together, bridging gaps in services, and providing sources of historical and local knowledge. Supporting and maintaining local communities was regarded as an essential component of a good life, and residents in each site noted the loss of accessible meeting spaces through austerity cuts which particularly impacted on young people.

Yet there were also recognised divisions in communities across all three of our sites – in Hay-on-Wye residents were conscious of the circulating narratives of possible dissension between long term residents, and newcomers. Several of our conversations in Hay included mention of ‘incomers’ or ‘blow-ins’, and ‘locals’, although actually defining what makes for a long term local resident was sketchy, “Someone said on Facebook it’s whether you’ve got six generations in the graveyard”.

Similarly in Woking there were comments on whether those new to the town would become active residents, or use the town as a base for a life in nearby London. In Stoke-on-Trent lines of dissension were more political than social in light of the Brexit vote and shifts in political allegiances. Across all three sites, however, concerns were also expressed for marginalised individuals, communities and groups of people, and how they could be made more visible when making plans within the community.

3. Green spaces

Communities do not only need designated rooms or buildings to flourish, accessible, pleasant green spaces were also identified as an important component of a ‘good life’. For Hay residents, easy access to hills, rivers and natural areas were not taken for granted – rather they were the main reason people returned to live there from elsewhere “Well, I couldn’t imagine living anywhere that was flat.There’s a lot of hills and mountains around here and that’s what feels like home”; Woking residents equally valued the canal, and parks, and its proximity to countryside (“It’s this town that pops up at the end of a green archway”), as did those living in Stoke-on-Trent (“It’s fantastic, we are within ten minutes of countryside”). Residents were united in all three places in the necessity of retaining these spaces in and around where they live and recognising the possibilities they offer for the future of their towns (“I have a vision of Stoke, it will be a green city because we have loads of green spaces”).

4. Good work, good homes

“Employment, that’s the main worry really, because they [young people] can’t really build on anything for savings, for a house, or anything, you know, getting a deposit and all that. They can’t plan for the future”.

Whilst the social and environmental aspects of where people live were identified as important components of living well, economic concerns underpinned possibilities for a good life. Enjoying green spaces, and a strong sense of community were clearly valuable for local people, but they also needed the security of knowing that jobs and careers were available, and that housing and homes were accessible and affordable.

In Hay-on-Wye and Woking house prices were inflated beyond the reach of many local people – by tourism in Hay and by accessibility to London in Woking. Whilst the cost of housing in Stoke-on-Trent was lower, high employment, limited job prospects and low wages left many unable to buy their own homes or prevented them from being able to move even a short distance outside of the city where house prices were much higher “If you think about properties in London, how they’ve gone up in price, you know, it’s not really spread to us. We’re still this like I don’t know, blot on the landscape, aren’t we?”

The young were felt to be most affected by uncertain job and career prospects and unaffordable housing. In Hay-on-Wye and Stoke-on-Trent there were real concerns that young people were not only losing out on employment, but also in opportunities to develop careers “there are a lot of young people here [Hay-on-Wye] with dead-end jobs who could be doing something. [They should] have careers and be able to earn and have a job they love rather than just living outside their jobs.” Although the regeneration and changes taking place in Woking should offer more prospects for young people to secure local jobs, there was a real concern that these would only be in the retail or hospitality industry, and even these prospects were in doubt because of the pandemic.

Conclusion – looking back and moving forward

Memories of the way things were in the past and experiences of living in the present came together to influence ideas about prospects for the future in each of the three locations we visited, ranging from a nostalgic longing for the way things used to be, to an acceptance of the need for change in order to move forward. Most saliently there was an acknowledgement that challenges to everyday living also offer opportunities for change and improvement. Our work in Stoke took place before the pandemic, but the city was facing its own challenges to its reputation as its population voted for Brexit, uncertainty over its future. Nevertheless, participants’ narratives were of aspirations for the future, of finding ways forward which drew on their cultural heritage and strong identity as ‘Stokies’. In Woking and Hay-on-Wye, the pandemic afforded an opportunity for re-appraising what is most important to people. Many of our participants expressed hopes that newly formed relationships, community support networks and the practices of simply remaining ‘local’ for shopping and leisure activities would continue. By appreciating what is good about where they live, learning from what works well and, most importantly, having an awareness of those in the community who need support, there were aspirations that the future would be brighter in their towns as the pandemic itself fades into memory.

The answer to the question of what constitutes a good life has often been presented in terms of an individual’s aspirations to live well, to acquire more, to provide food and shelter for themselves and their families, and to participate effectively in the life of society. Yet, as we found in our own places, this approach neglects the broader realities and challenges of everyday life, where material circumstances and context shape possibilities for living well.