Economic growth—our modern day religion?

“Every society clings to a myth by which it lives,” Tim Jackson wrote in 2004, and “ours is the myth of economic progress.” For many economists, those who call for an end to the growth paradigm are utopian fantasists. But, as CUSP researcher Richard McNeill Douglas writes in this blog, the idea of eternal growth is itself deeply fantastical.— (This blog is an edited version of a talk given for Promoting Economic Pluralism in Dec 2018, and also appeared on the Renewal Website.)

Economic growth is the religion of the modern world, the elixir that eases the pain of social conflicts, the promise of indefinite progress. It offers a solution to the everyday drama of human life, to wanting what we don’t have. Sadly, at least in the West, growth is now fleeting, intermittent.

These are the words that open The Infinite Desire for Growth, a book published this year by Daniel Cohen, professor of economics at the École normale supérieure in Paris. I begin with Cohen’s remarks because they raise a number of questions I would like to explore. Is economic growth our modern-day religion? What do we mean by ‘religion’ in this context? Is faith in this religion, if it is one, fading—‘at least in the West’? And is this a good or a bad thing?

The decline of growth: a tragic story

As Cohen presents it, growth is a good thing, not just for its material benefits taken on their own—although these should not be downplayed, nor should the hopes of billions of people around the globe for a more equitable distribution of them. But for Cohen, growth is good not so much for its material as for its social and psychological benefits. It gives us something to focus on, to strive for. And it needs to do this, Cohen says, keying into a mainstream current of economic thought going back at least as far as the ‘marginal revolution’, because no matter what level of material wealth we enjoy, it will never be enough to truly fulfil us. Cohen writes:

Like a walker who never reaches the horizon, the modern individual wants to grow ever richer, not understanding that such wealth, once it has been achieved, will become the normal state of affairs, from which she will again want to distance herself. […. H]uman desire is profoundly malleable, influenced by the social circumstances in which it finds expression. That makes it insatiable, infinite.

Economic growth, then—or rather the civilisation which makes a religion of it—is presented here in a quite tragic form. Albeit, while growth holds good, this is a kind of suspended tragedy. What brings this tragic quality home to us is when growth starts to give out. For, if growth is a religion, as Cohen suggests, then it is one whose god has become remote, unreliable—and perhaps soon to be declared dead in any case?

Cohen discusses a range of reasons as to why this modern faith is becoming harder to maintain, but—in common with the analysis presented in this country by Tim Jackson—the two main ones are secular stagnation and ecological limits. Secular stagnation—a slow exhaustion of opportunities for expansion of the real economy—has resulted in declining growth in developed economies as a whole, and specifically for the majority of Western workers, since the 1970s. Even more importantly, ecological limits make it impossible to radically decouple economic activity from environmental impacts, which in turn places absolute constraints on future growth.

Cohen likens the resulting mood we are experiencing today to the ‘spiritual angst’ of the European mind in the seventeenth century, as it struggled to adjust to the waning of belief in the presence of God in a scientific universe. Today’s politics of xenophobic scapegoating comes as no surprise to him in such bewildering times.

What Cohen presents us with is a story, then. It’s a story in which the pursuit of ongoing economic growth provides whole societies with a sense of meaning. But, as with any story, it’s one with a beginning, a middle, and an end. And we are now perhaps at the beginning of the end. Trying to wring more growth out of the system is increasingly making the majority of us unhappy—and destroying the environment at the same time. We’re beginning to perceive that it can’t go on forever, and that’s reducing the faith we have in it. We are increasingly falling prey to, as Cohen put it, a spiritual angst.

So that’s one story we have, then. But it’s not the only one. There’s another story—one which takes much of this same material, and accepts many of the same challenges, but turns it into something else. Providing us with a happy ending; or rather—and this is the crucial bit—no ending at all.

The story of endless growth

In October the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel—commonly known as the Nobel Prize for Economics—to Paul Romer and William Nordhaus.

Romer, celebrated as a pioneer of ‘endogenous growth theory’, was awarded his prize ‘for integrating technological innovations into long-run macroeconomic analysis’; Nordhaus his ‘for integrating climate change into long-run macroeconomic analysis’. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences summarised how their work intersected as follows: ‘Nature dictates the main constraints on economic growth and our knowledge determines how well we deal with these constraints’. Romer’s work was thus presented as concerning the economics of reconciling growth with environmental limits.

It was in this capacity that Romer’s award was celebrated by those opposed to environmental arguments on the need to constrain economic growth (or to work with its limitations). Take, for example, the sustainable investment expert Michael Liebreich. In an article entitled “The Secret of Eternal Growth” Liebreich described the awarding of Nobel prizes to Romer and Nordhaus as ‘a huge slap in the face for the champions of “degrowth”.’ Liebreich, it should be pointed out, is an environmentalist himself, and argues for urgent action on climate change. His main point is that what this requires right now is massively-accelerated investment in low carbon energy; and that this is less likely to be forthcoming if the mood music coming from environmentalism is anti-capitalist. In this sense, he describes himself as an ‘eco-pragmatist’.

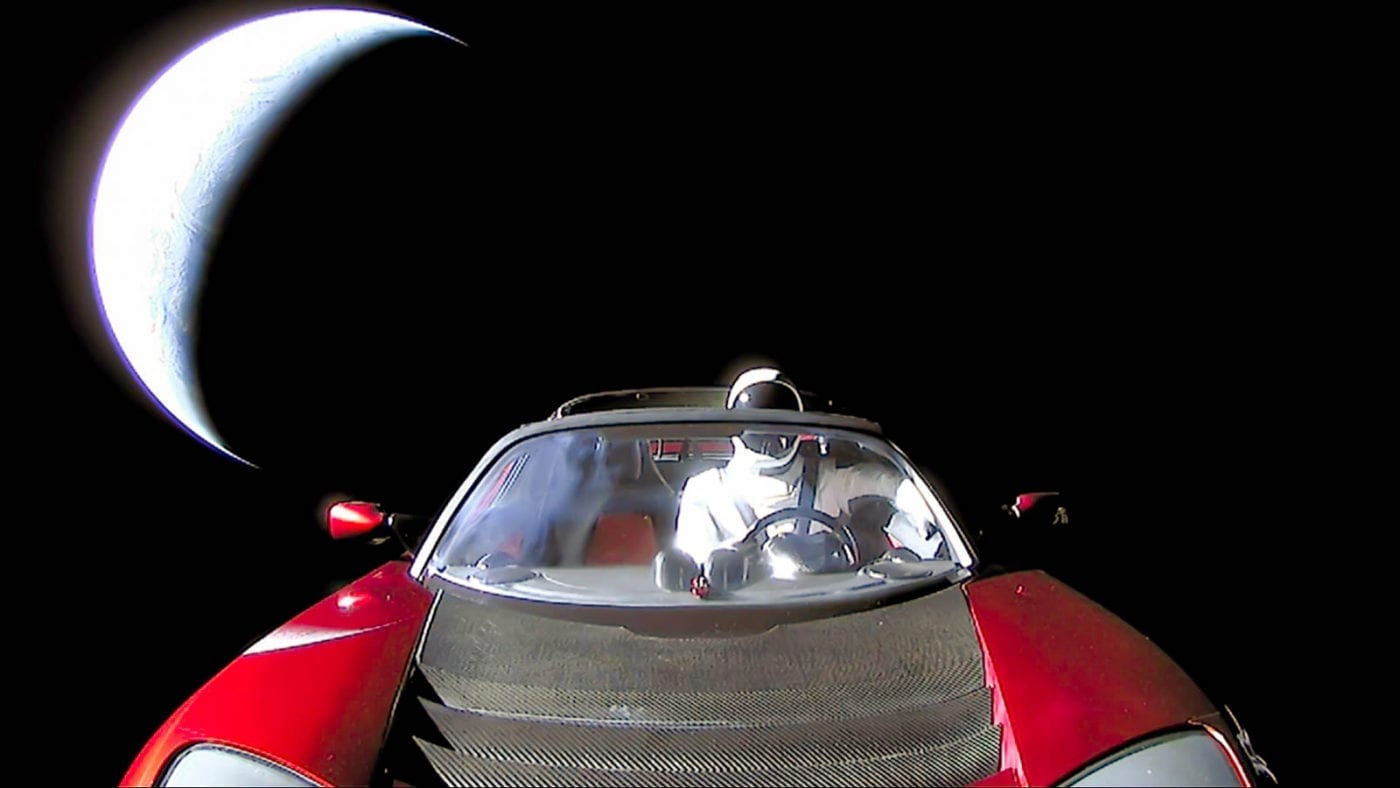

Liebreich certainly has rational grounds for his approach, in terms of encouraging wider support for urgent low carbon investment. But let’s look closer at the language he uses, and see how pragmatic it looks. In using Romer’s work to suggest that ongoing economic growth is compatible with mitigating climate change, Liebreich makes the far-reaching claim that ‘there is nothing in physics to stop the economy from growing forever.’

How does he support this argument? He begins by criticising the way in which ecological economists have grounded their economics in the physics of entropy. He describes this, provocatively, as an example of ‘fake science’. This is because the Earth ‘receives a huge daily flux of energy from the sun’; and thus solar power ‘could well be’ the ‘key to endless growth’, ‘proving that the economy can grow for as long as there is still a sun in the sky (which would give us about another five billion years).’

And it is not only energy from the sun that will allow for such seemingly endless growth. Liebreich refers us also to human ingenuity. It is this, the creative power of our minds, which will enable us to dematerialise the entire economy. As he tells us: ‘material efficiency and recycling will improve indefinitely; the extraction of materials and production of pollution will first peak and then asymptote to zero.’ And this combination of ‘unlimited knowledge’ and clean energy will thus ‘drive endless improvements in human wellbeing and flourishing.’ Finally he concludes:

We should approach the task with optimism [….] because, as Ronald Reagan (displaying a more thorough understanding of thermodynamics and economics than the entire degrowth crowd) once said: “There are no such things as limits to growth, because there are no limits on the human capacity for intelligence, imagination, and wonder.”

I just want to highlight something in these words. What do we see here? ‘Eternal growth’, ‘growing forever’, ‘endless growth’, ‘billion years’, ‘improve indefinitely’, ‘to zero’, ‘unlimited knowledge’, ‘endless improvements’, ‘no limits’… This is the language of the absolute. These are clues, I would suggest, that this type of thinking about economics is anchored in a profoundly metaphysical conception of reality.

Where does this thinking come from? The reference to Reagan gives us some clues. Reagan himself was popularising arguments which had been developed by a number of environmentally sceptical economists, not least Julian Simon. Simon, in turn, drew—and exerted his own influence—upon a range of economists whose primary focus lay outside the environment, not least Friedrich von Hayek. It might be possible to talk of a Hayek-Simon-Reagan axis of ideas—Hayek providing the main framework of economic ideas, Simon developing these specifically to counter the ‘limits to growth thesis’, and Reagan communicating the sentiments at their heart to a mass audience.

These ideas have become aspects of economic common sense in much subsequent debate on the environment. Taken together, they add up to a metaphysical construct we will all be familiar with: ‘economic reality’. To highlight its metaphysical nature, let us look at the interplay of three ideas in particular: the idea of the mind; the idea of technological progress; and the idea of the market.

The metaphysics of ‘economic reality’

Regarding the mind, what we find in this discourse is the idea of the mental as the essence of limitlessness. This is visible in the emphasis on fantasy as the characteristic mode of mental activity, Reagan’s speeches, for example, being littered with references to ‘dreams’ and ‘imagination’. It’s visible in the assertion of the insatiability of human desires. And, most of all, it’s visible in the idolisation of ingenuity, giving rise to widely-cited arguments along the lines of stating, as one obituarist of Simon’s put it, that: ‘Supplies of natural resources are not finite in any serious way; they are created by the intellect of man, an always renewable resource.’

Regarding the second idea, that of technological progress, here we find another respect in which the limitlessness of the mental is projected onto the physical. What this means is that an observation of historical progress since the industrial revolution is first hypostasised into a law of history, and thereby assumed to hold for the foreseeable future; it is then projected forwards into a speculative consideration of the far future, by which time, through a simple additive process, it is assumed our technological capacities will have grown to near infinite abilities to translate will into reality. And this impression of near infinite power is then projected backwards again into the present, and onto the agency—human ingenuity—held to be responsible for the historical progress witnessed to date.

Finally, there is that third idea, the market. In the work of Simon and others, in turn drawing on that notably of Hayek, it is in the market that minds are put into contact with each other, generating a kind of collective intelligence—turning ‘the human race [into] a collective problem-solving machine’, as the environmental sceptic Matt Ridley puts it. What connects individual minds up together are the twin mechanisms of individual economic incentive and the price signal. For many environmental sceptics—such as the welfare economist, Wilfred Beckerman—so long as markets are allowed to work freely, this means ‘we will never run out of anything at all. Anything.’

To conclude, what we see here is an intellectual process in which the mental is conceived of as being limitless; and through economic growth (understood as the market-driven application of ingenuity to overcome material limitations), the natural world is increasingly made subject to—its resistance to our will dissolved by—the mental, and so is infused with the mental’s quality of limitlessness. Far from being the hard-headed vision of the pragmatist, then, what do we find in ‘economic reality’ but the product of a belief that the world is mind—or, rather, is progressively becoming so?

Conclusion: when faith meets reality

All of which might well provoke the response from the enthusiasts of the market: ‘So what?’ If this pursuit of growth is less a matter of hard-headed science and more a kind of religion, is there anything so very wrong with that? A religion, after all, is a belief-system which imbues one’s life with a sense of meaning. The meaning of growth in this case—if one rejects the pessimistic conclusion which Daniel Cohen applies to it—is of an endless quest to improve the material conditions of human lives. And this is something, we should readily recognise, which can be appropriated by the left (running from liberal ecomodernists, through to Post-Keynesian Green New Dealers, and all the way to Fully Automated Luxury Communists) just as much as the right. Isn’t there something to be admired in this faith?

Of course there is. So what’s the problem? The problem comes when faith is maintained in the face of reality. Then it becomes blind faith: and it is at that point that the pejorative presumptions about religion as being an essentially irrational force begin to acquire their merit. The clue we need to tell us we have reached this point is that the arguments for the possibility of indefinitely overcoming the entropic limits to growth depend on literally fantastical terms. As Ronald Reagan himself put it:

There are no such things as limits to growth, because… it’s not what’s inside the Earth that counts, but what’s inside your minds and hearts, because that’s the stuff that dreams are made of…