It’s the sort of area you don’t tend to arrive at with pleasure, and when it’s the place you have to go to lay your head and pay your bills, it can be a hollow. Much less wild life here than anywhere else in town. Even the cemetery. And you feel the deficiency deeply if, to you, Nature is the measure of reality.

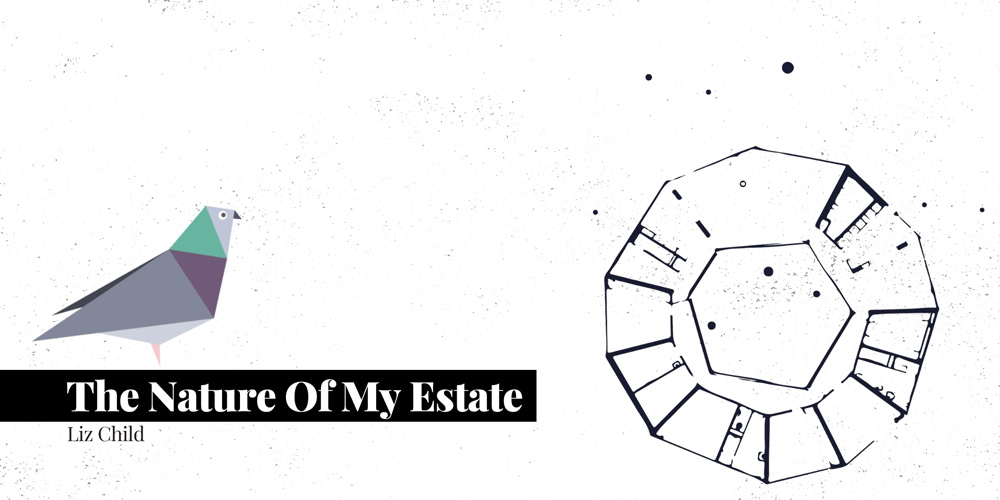

Should a camera-drone look down on a doughnut shaped town, this estate forms the hole in the middle. The buzzard’s eye-view reveals a desert within, attested to by last year’s Google satellite image. Circular is the road fringed with blocks of flats and stuffed with two terraces of old-folks sheltered bungalows. An encirclement striated with seared lawns sloping down towards the Tesco Express.

Losing Nature afflicts the nourishment of everyone’s lives and livings. Where a sighting of a fox could be a joy, the darker thrill of moaning at the man who left the bulging rubbish bags out overnight suggests pack-dominance behaviour in an over-fed human population. Fox seeking sustenance finds scant nourishment, on the other hand. Delving swiftly, unseen, leaving contents to scatter into the four winds. Daisies, dandelions, hawkweeds and the food chain they supply, labour unfairly too. Should we tune into them, into our human ecology of here, we would catch what they have to say to us.

Planners of the 1960s, promulgating a ‘new modern community’, designed out habitat for most living creatures, fashioning instead ubiquitous lawns, colourless buildings and a glut of young people with nowhere to shelter. Grown people laboriously haul shopping up the sloping, cracking footpaths, bewailing the Council, deploring their luck and their place. The conceit of Progress ejected much of what makes a human Human—the relationship with Nature.

The only creatures playing on the lawns in daytime are the contractors, mechanised humans from the Council playing tag with the trees, seeing how close they can strim to the trunks. Others jiggle in their lawnmower seats, skimming the lawns to the rhythms playing in their headphones. They are unacquainted with life-blood sap rising through the phloem just below the bark. They are unmindful of the predatory life form they become when in control of their machines. Bees and hoverflies would like to thrive on the daisies and hawkweed these humans mercilessly behead. Fortnightly I watch the seasonal rave of these beings, questionably being Human at all. If I had my own lawn I’d invite wildlife creatures or gardeners to play. Mechanized humans I would outlaw with policy.

There are a few pleasures of Nature here. Specimen trees grown tall and admired, as long as leaves don’t drop or their branches don’t lean. Of the mature ones: ten birch, one sycamore, one rowan, one field maple, one alder, two weeping willow, two younger flowering cherry—but one dying from a strimming wound—and a lilac bush thrusting itself out of the base of a wall. Of next generation saplings: zero birch, zero sycamore, zero rowan, zero alder, zero weeping willow, and zero flowering cherry. You get the picture? And for an impression, a red-oak exotic memorial tree to a past district councillor, lest we forget. Conversely, no flowerbeds or bushes to honour beetle, bird or butterfly. No mulched corner, pond or leaf-pile for them to call home.

By contrast, the body of the doughnut nourishes Nature. A life-belt. A sanctuary plump with back gardens, decorated with pollen plants, patterned with refuge hedgerows, sprinkled with fence-post lookouts and sheds to breed beneath. The fruitful wooded edge by the old church hall bristles with ostentatious brambles. These are wildlife’s nearest residences. From here they come moseying into our overly lit night-time zone, finding a surplus of pies and squashed sandwiches dropped by teenagers on their way home from school. All are gone by morning. Wrappers left to roll along the grass or soar on gusts into the trees to be caught, flapping, ripping, toward their inevitable micro-plastic end.

Worms, full of wonder when long, fat and healthy, commonly slog across the tarmac wastes in search of moisture-filled gullies, but falter in the heat. The birds that would pick them off are few and far between thus giving time for lumbering pensioners, ex-allotmenteers perhaps, and small children with primal understanding of a worm’s value, to assist them to the drains. Survival is perilous when they leave the parched banks, in an April short on showers.

Speaking of dryness, the daffs are complaining. A poor display this spring after last summer’s drought. Their small cry of “Spring is here” preceded a quickened gasp. The crocus bulbs I guerrilla planted along the foot-path bank emerged only to topple, as if unrequired to make useful nectar for any passing insect.

A pied-wagtail pair patrol across the short grasses, heads bobbing and tails pumping, investigating insect potential and finding little. Invariably, the crow family harry them, assuming protection of the hidden larders that they buried in stealth and deftly memorised. The pestering of the crow is fabled. Once wagtails are seen off, defensive of valuable territory they are storming up to disturb the buzzard gently soaring over our desert. From their roost in the tallest birch tree, the crow family dominate the bird-scape, but for the growing population of gulls.

The flats take the brunt of the impact. The apex of the roofs become white streaked cliffs, but remain un-nested peaks. Gull cries delude us that we live on the coast, but it is only cars that come in waves rumbling like the sea in the night, whipping up tension like the froth caught on a beach, and occasionally leaving a hedgehog or cat’s corpse tangled in a dusty tide line at the kerb.

The gulls and the crows rarely skirmish. Contention however, simmers just below the surface of the overgrown human population and their canine companions. A lack of everything also precludes a dog play park. Having in mind fiscal punishment, owners guiltily bag their dog’s leavings. We monitor from our kitchen windows as we all know there aren’t enough slugs, or rain for that matter, to deal with fouling chunks of faeces. And the crows don’t have the guts for that sort of detritus.

Neither does the green woodpecker who sails in on odd occasions, displaying his magnificent plumage of black and white trim edging lime green wings. His arrival call, a three-note exhortation, “attention, it’s me, it’s me”. Imperiously he hops about propping himself on speckled tail feathers trailing like a military tail-coat. He glares and flashes his red balaclava, watching for trouble. Our scattering of specimen trees is hardly a protective hideout but he has no need of one, for no one will mess with the stout sword he stabs at the ground with. His thrusts are too fast to see the forage he gleans, but when winter arrives at the doughnut’s edge and the snow is on the ground, he comes for fallen apples. A spirited muse against the bright white world for a day.

The robin trills the dawn chorus now that the blackbird has been silenced by the crow family. She trills alone, with no responses heard from distant trees. A blue tit attempts harmony later, but sounds unsure of himself. Their efforts seem to be keeping an age-old tradition alive in the hope that Nature will retrieve her place once humans recognise the loss. A re-enactment, lest they forget. We have already forgotten the cuckoo.

Absurdly, my CD of birdsong arrived today. Sent by the RSPB’s campaign that aims to increase awareness of the plight of bird populations, by raising it high into the record charts. Hoping, justifiably, that human society will hang its head in shame, and accordingly adapt its behaviour.

The robin, while waiting for us to catch up, has done so and learnt the craft of bird-feeder hanging. It took some time flapping, stressing, assessing, testing sufficiency of support on the short metal perches for her chubby, pink-bibbed bulk. In their long history robins have followed pigs in the small-holdings, picking off grubs from the snuffling porcine excavations. When the pigs and the small-holdings went they adapted to follow gardeners as they dug their trenches, perching on spade handles waiting for a gardener to return from its tea-break, awaiting worms. Now comes the age of no-dig gardening, to which they must adapt yet again. Bird-feeder hanging must be a misery, but is a ‘needs must’ here-abouts and nowadays.

Still unsure of her prowess, she gives way to the goldfinch flock, the strutting chaffinches and the tag-along greenfinch, all with readily adapted stubby beaks that break and chew and drop seeds for the ground-feeding wren and dunnock. In time robin beaks or bulks could adapt to seed cracking and perching specialisms, but for now she hangs on in tentative harmony with blue or coal tit, confident in her larger presence despite her slighter skill.

From this catalogue one might think an abundance of bird life abides here, but not so. It is a last refuge. When a pair of tree sparrows turn up to feed they bring a fearful reminder, for if they are here then they are not there. Elsewhere is no longer hedge or woodland to hide from sparrow-hawks on their daily sortie, or from the contractor’s netting. These brown-streaked beauties bring notice of diminished countryside out there beyond our doughnut. Once I sang with joy at their irregular visits, now the pain of their subsistence flies in with them, jabbing at my guilt. Few of us can afford to care, for persistent survival is also our modus operandi. The bird-feeders become the saviours of souls, both the sparrow’s and ours.

Lichens, the remainers cleverly more resistant to air-pollution, Lecanora conizaeioides and dull yellow Xanthoria parietina sparsely colonise tree trunks or try their luck on concrete roof tiles. Resigned, they wait for the opportunity to revive the ecosystem, as their ancestors have done before them. A crew of plant-life builders, inclining their skills at moisturising, mineralizing, nitrogen-fixing, coexisting, waiting to be requisitioned once humans change their habits. More elaborate varieties are long sacrificed, their monitoring completed, job done, no retirement, just dusted to dust, by chemically-loaded winds of contamination.

The lawns dry out as they vaporize invisibly and temperature differentials become all wrong. Moisture accumulates in the skies overhead when it should be absorbed in the soils. It traps smoke from distant fires making grey days greyer and settles dirtily on our white plastic window sills. Swilling cloudbursts pour down, flushing soil to the gullies and kerbs, where sycamore seeds take the chance offered at a dogged attempt to grow. It doesn’t take long to desiccate. As the moisture stays bonded in carbon-filled clouds the gentle daily dew is thwarted. Patches of bare soil allow deep-rooted, colonising hawkweeds their flower-head. Desperate insects act fast to draw nectar before the next weed beheading takes place.

South-facing banks enduring climate-changing sunshine crack open again, this time in April, not August. Mosses falling from concrete roof tiles make plenty of material for nesting, but no one wants to build nests with dried-up prickly moss. It lies on the ground for all the world resembling miniature hedgehogs curled and protective, reminding us of the absence of the real ones. Once correctly identified, dried moss is swept away and denied the opportunity to grow into soil.

Irony strikes when a quarterly posted through our letter boxes advertises the pleasures of seasonal visits to glorious gardens. Articles on spring plants we might find “making everything fresh and green and bursting with life”. Life doesn’t burst here, it wavers. Two autumns ago, a lone birch bolete appeared beneath the twin-stemmed silver birch. None since or before in the five years I’ve looked out on that spot.

Outmoded council policy requires permissions to plant a shrub, bans climbers from growing up walls and threatens our tenancies if we are found feeding pigeons. The designers, the overviews, and the attitudes of our council benefactors hide behind the times, behind the trends, blinded to bio-diversity loss and climate emergencies. Affecting a perplexing tenant-Council relationship based on benevolence to the subordinated. One that buttresses every council estate in this country, I venture, and one that underpins an even greater subordination, the shrinking of the wildlife-human relationship.

Community Acts allow a turn-around. We make our demands, as Community head-butts with the Council, and power shifts. The subordinated become united. Within a tenuous harmony exploration of working with Nature begins. The time for Community Gardens has arrived and, as funding flows, the entropy shall reverse as we compost and plant together. We will stand our ground like bears, and be photographed as if pandas, and it will become our haunt to retrieve and mend. Appropriate wildlife will revisit. We carefully do not use the term ‘rewilding’, although that will be what it is for the emergent ecological-mind.

Enticed by barbecues, gathering gradually into a band of naturalists and growers, gardening busy-bees, the old and the skill-less. We aim high looking to changing middens into Gardens of Eden. Slowly, conjecturing, we learn to change small corners with gentle impressions, adapting like the robin to build our skills and confidence. Tentatively trying out the powers attributed to a constituted community group, surprising ourselves with success. We spread the word in consultative conversations as if a bee waggle-dancing in the hive, saying: “One day it could look like this.” “Other towns do it and so can we.” “Of course, we shall look after the wildlife. We need them to come.” “No, we do ‘no-dig’, you won’t hurt your back.”

Meanwhile, I watch the buds plumping up optimistically on the trees, while we plump up the hopeful dreams of resuming natural abundance. The ubiquitous lawns cascading down towards the Tesco Express one day may be apple orchards, and fields of fruit and new birch and more rowan and nesting birds and ponds with toads and flowers and insects, and food for all in all. Humans and wildlife alike may harvest as they forage new desire-lines, adapting deeply as they go. And the worms will remain safe in the banks and the flowerbeds.

The buzzard will monitor us while we courageously adapt. In hope, we will send the camera drone up to look down on our re-habited charm of thriving abundance. The more satisfying of doughnuts are full and diverse. So, I will watch for the day the buzzard settles in the tall birch trees by the foot path and the robin goes back to resting on spade handles. It will tell me that Nature’s abundance wants to re-inhabit my estate.

. . .

About the author

Liz Child is retired, and weary of the many years that she has watched Nature being disregarded and harmed, so she has taken to writing. Her early work life was in manual and care work until, in her 40s she studied human ecology, and now is an advocate for agroecology, permaculture and community gardening.