Drafting Sustainability: The Virtues of Translating Policy into Legislation

In his guest blog for CUSP, Daniel Wortel-London, a US Federal policy specialist at CASSE, argues that translating sustainability policies into legislative drafts can enhance our research, boost persuasiveness, and facilitate implementation.

Guest blog by Daniel Wortel-London

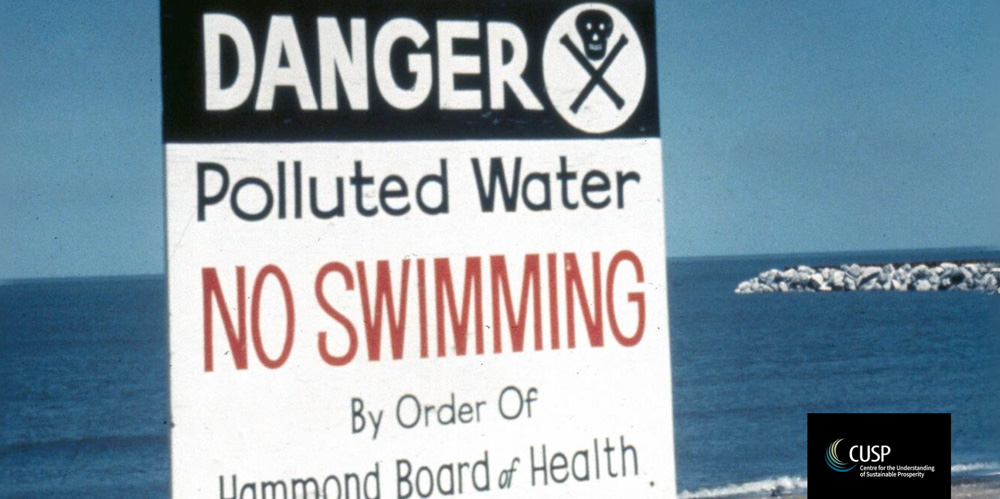

The 1972 Clean Water Act specified that the aim of the law was to ensure that the United States’ waterways were “swimmable.”

Now, what does “swimmable” actually mean?—Is it simply a body of water that isn’t radioactive? A water clear of debris? Water entirely untouched by humans? And how would you exactly test if water was “swimmable”?

Addressing these kinds of issues marks the difference between proposing sustainability policies and drafting those policies into law. For its often only by translating policies into enforceable language that you can identify the subsidiary—but substantive—issues that need to be addressed to make the law complete (like defining “swimmable”). Drafting law forces you to think problems through and point out inconsistencies and administrative/legal/practical difficulties that might come about in attempting to solve them.

In short, drafting law is where vague policy ideas become operationalized. And by making our policy ideas operation-able, we make them more concrete and compelling for both policymakers and the public-at-large.

Thinking Things Through

Those of us in the sustainability community are generally concerned with problems and how to address them. Our solutions to these problems vary, of course, depending on what actors we want to target (individual firms, sectors), using what instruments (information, taxations, subsidies) and through what mechanisms (the market, command-and-control regulations. But whether our proposals tend towards the utopian or more realistic, the main thrust of our proposals tend to revolve around what measures will most directly impact the problem we are concerned with.

But identifying the “main thrust” of a policy is just the tip of the iceberg. For a law to actually being passed, for example, it generally needs to be aligned with existing laws and the administrative, budgetary, procedural, and other rights and duties they impose. A law which doesn’t identify and address inconsistencies between itself and this existing law can be easily nullified—no matter how well-intentioned it is.

Policies also exist in a pre-populated linguistic context that advocates must attend to. For example, the meaning of “shall” in U.S. statutory law means something significantly different than “may.” Entire laws can be thrown out, or carried out in a way contrary to the sponsors’ intention, based on whether a few words are used properly or not.

Perhaps most importantly, policies can only be carried out if several ancillary but essential questions are addressed first. What department or administration will implement the policy? What additional funding or powers will they require to carry it out? Do existing laws need to be amended in order to avoid conflicts with the policy? How will the effects of the policy be monitored? Who will be accountable for adjusting the policy if needs require? And what will the penalties be for not following the policy?

Many policy proponents address one or two of these questions while developing their proposals, of course: but rarely are they all thought of together. And it is only by methodically checking how our policies can be operationalized in a given legal and administrative context that we can even recognize what questions we are failing to ask – and what research we need in order to answer them.

The Rewards of Wonkery

Addressing these kinds of questions can be difficult—I can attest to that. But the rewards are well worth it.

First and most obviously, drafting bills into enforceable and legal statutes will help these laws get passed. Yes, it’s possible for a friendly policymaker and their staff to do this for us once they are receptive to our ideas. But policymakers often don’t have time for this: rather, most of their time is made up of grabbing pre-formed solutions to existing policy problems. And even if sustainability advocates have thousands of good ideas, most policymakers will not want to go through the trouble of making them legal and operable. They’d rather pick up the ones that are relatively well-formed—and unless we do the work for them, lobbyists for polluting industries will be more than happy to provide policymakers with alternatives.

Second, by attempting to make our policies concrete we can help winnow down a relatively wide range of sustainability policies into a few that are legal, concrete, and attractive. There is no shortage of sustainability policies of course: but this very breadth can be a problem. We don’t know which ones to rally around, and the very scope of our policy solutions leaves many operational questions unanswered, confusing both policymakers and potential supporters. Addressing these questions, and clarifying which policies are more “realistic” in our current legal context can both help us focus our efforts and win new constituencies to our cause.

Finally, translating our policies into law can help us find legal routes for “scaling them up” in order to be more effective. Many sustainability “best practices” tend to be focus on examples of local implementation, such as within regenerative agriculture, with the hope these efforts will eventually percolate across broader scales. But translating local or municipal policies into those addressing regions or nations is far from simple – not least because the legal and administrative context across these jurisdictions can vastly differ. Drafting laws, however, can help us identify pathways for addressing these differences, thus heading off challenges on our way to scaling up local solutions.

Conclusion

Writing policy is, of course, not sufficient to developing a flourishing civilization within planetary boundaries. We need to make the problems with our current economy clearer to more people. We need to make the prospect of a sustainable future more compelling. And we need powerful social movements, sustained by new forms of economic production and consumption, to help propel these solutions into the policy realm.

Nonetheless, ideas do not become policy automatically. If we are serious about using policy as one means among many for achieving a sustainable future, we need to be serious about the process of policy-writing.

As policy specialist for CASSE—the Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy—, I’ve drafted nearly a dozen “model” sustainability bills, and plan on writing several more. I can attest that this work can be difficult—but the insight it brings is incomparable, and the future it can help bring is worth everything.