You And Me Here We Are

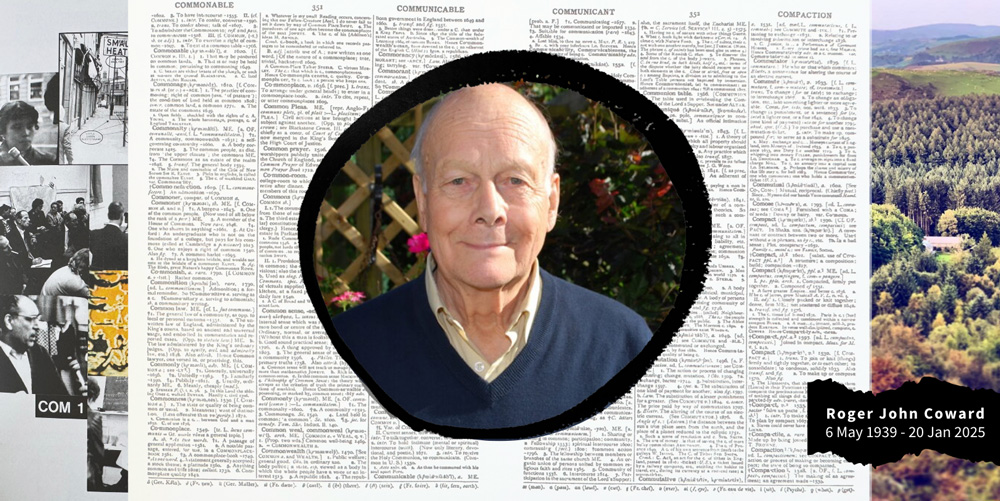

A eulogy for Roger Coward MA, Film Maker, Teacher, Psychotherapist, Author, Musician—and PhD Student with CUSP. As read at his funeral in Abbeycwmhir on 11th February 2025 by Prof Tim Jackson, CUSP co-Director.

Roger arrived in the world (not necessarily for the first time) on 6 May 1939. He was born at Malvern in Worcestershire, the son of the Reverend John and Olive Coward. His brother Paul arrived five years later.

When Roger was six, the family moved to Orpington in Kent and later to Boscombe near Bournemouth and then Bristol. As a youngster, Roger was an enthusiastic boy scout and eventually became a Queen’s Scout, the highest award achievable in the scouting movement.

At one point he had ambitions to follow his father into the Church. But on further reflection, he decided that his future lay elsewhere. He won a place at Bangor University to study history and philosophy. And not long after graduating, he joined an expedition to East Greenland led by the eminent explorer and deep sea sailor Major HW (Bill) Tilman.

Roger had some experience sailing dinghies but it can’t quite have prepared him for the North Atlantic, where his role was to film the pioneering voyage. He borrowed a 16mm camera. Bill paid for the film. And the Bristol Channel Pilot Cutter “Mischief” set off from Lymington on 30 May 1964.

A full account of that journey is given in Tilman’s book “Mostly Mischief”. But it’s worth mentioning one memorable stop along the way. Following a series of eruptions, a small area of volcanic lava suddenly emerged from the sea, in April 1964, just off the south-west coast of Iceland. When the crew of the Mischief arrived there a couple of months later, they were probably the first to step foot on the brand new island of Surtsey. It was Roger who captured that momentous landing on film.

Years later, Tilman was still sailing the seven seas. At the tender age of 80, he embarked on another perilous journey—this time to the Antarctic. Sadly it was a destination he was never to reach. The vessel foundered somewhere between Rio de Janeiro and the Falkland Islands and Tilman was never found. But when the BBC commissioned a documentary about the Major’s life, it was to Roger’s film ‘Mischief in Greenland’ that they turned for footage of their earlier more successful voyage together.

Meanwhile, Roger himself had chosen a slightly safer profession. Back on dry land, he started working for the BBC where he became an Assistant Producer on the children’s show “Blue Peter”. In 1966, he married his first wife, Dagmar and they adopted a son Jan—known affectionately as Hobbit. (By the way, the couple also had a dog called Frodo, in true Tolkein style.) Sadly their life together was marred by tragedy. Dagmar died of an inherited kidney disease and Hobbit too died at the young age of 28.

Roger sustained a lifelong interest in the arts. He produced and directed a number of plays at the Royal Court Theatre. He also directed at the International Fringe in Edinburgh and at the Soho Theatre in London where his production of ‘Jack’ was subsequently televised by the BBC.

In December 1971, he was strolling along the South Bank in London, pondering the subject for his next film, when he happened to see a sign outside the Hayward Gallery for an event on ‘art and economics.’ The event was free—and Roger had very little money at the time. So he went inside ‘to satisfy my curiosity’ he said.

That curiosity led him into a decades long engagement with the Artists Placement Group, a ground-breaking British experiment which aimed to bring art into industrial and governmental settings. Roger was invited to join the group at their meetings in the home of the conceptual artists John Latham and Barbara Steveni. He later described those meetings with a typical affection.

‘Inside this potentially smart Georgian House in fashionable Holland Park all the plasterboard had been taken off the wall studding,’ he wrote in 2015, ‘and only the kitchen area was lit, leaving eerily dark pools of light behind the vertical, nail-bitten wooden struts. A cat wandered between the timbers and the group’s legs as we drank our allocated small can of beer.’

And then in 1975, Roger himself became the first artist from the group to be placed in government—in the Department of the Environment.

Little Green was a district of Small Heath in Birmingham. Its residents described it as a war zone. ‘Crumbling ruins, damp, draughts, poor sanitation and unreliable utility supplies made them and me angry,’ Roger remembered later.

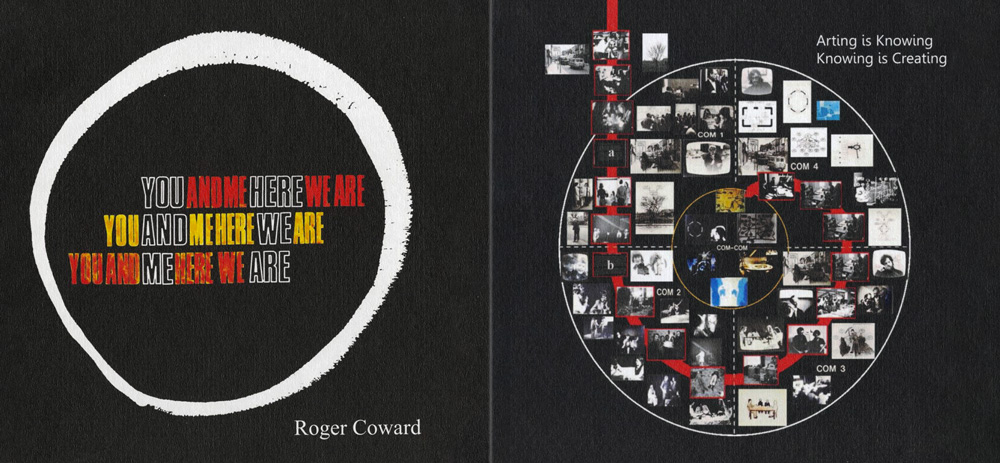

Representing those concerns to Birmingham City Council was not just an artistic project but a way of campaigning for change. And the resulting film installation—You And Me Here We Are—was eventually shown all over Europe. It was even revived forty years later by the Eastside Gallery, shown again in Birmingham, Liverpool and Germany. The artwork is now stored at the Tate Archive in London.

There was for Roger no real distance between art and life. ‘Most of the value of art comes from its context and not from the thing itself,’ he once wrote. And in the mid-1980s he began to teach what he had learned in practice. For twenty years he worked as a Senior Lecturer in Film Making at the University of Westminster.

While there he also trained as a Psychotherapist and soon developed a successful therapeutic practice first in London and then, later, in Powys.

Knowledge was never simply an academic pursuit for Roger. He had a lifelong interest in astrology and spent hours studying ancient routes and ley lines. And a couple of years after joining Westminster Uni, he purchased a run-down house and barn on a smallholding just over the hill from here. He dreamt of turning Cwm Bedw into a rural retreat for those interested in art, philosophy and spirituality.

Not far into that project, he was deep in meditation one day, when he had a vision of a huge equal-armed cross laid horizontally inside a wide stone circle. He immediately commissioned a design from the late Brian Parfit and together they set about constructing that same symbol in the grounds of the house. It became the focus for a monthly meditation group held at Cwm Bedw between 1991 and 1998.

And then in the year 2000, Roger met Sandy Underhill. She was undoubtedly the inspiration Roger needed to ground himself in the art of living as well as in the living of art. He retired from Westminster in 2006 and in the same year, the couple were married right here in Abbeycwmhir Church and moved into Cwm Bedw permanently. They worked tirelessly—with more than a little help from Sandy’s brother—to renovate the house and barns.

Many of you already know of Roger’s deep involvement in the community. He was a keen pianist and for many years played every week in the Titley Orchestra. He wrote and produced a history of Abbeycwmhir. In 2015 he became Chairman of the Abbey Cwmhir Heritage Trust which he ran for seven years. During that time, he and Sandy also established a successful holiday let at Cwm Bedw, where they generously introduced their visitors to the other-worldly tranquillity they had nurtured together in a small corner of these beautiful hills.

Among those lucky guests was a Professor at the University of Surrey and his partner. In retrospect, I can’t help feeling that Roger conjured us up in meditation too. At any rate, when he casually mentioned one day that he was looking for someone to supervise his academic research on ‘advanced meditation as a form of scientific knowledge’ I was immediately intrigued. And so, at the tender age of 80, Roger embarked on another perilous journey—towards a PhD. It was, sadly, a destination he was never to reach.

His health had already begun to deteriorate and in 2021 Cwm Bedw was sold in favour of a more practical home with Sandy in Nantmel. But he never gave up on that doctoral journey. Just two days before he died he was still talking to me about his plans for the work. Plans I’ll do my best to honour more fully at some point in the future.

‘I am concerned with being precise,’ he wrote in August 1975 about his work as a film-maker. ‘A transparent continuum exists between me and the screen—and on the other side, between the screen and you. To relate to you I have somehow to drop into this continuum a mix of colours. One after the other. Knowing that they will twist and dissolve, or blend and be obscured as they sink towards the screen. I must allow this to happen.’

‘All activity, not only writing and arting, is to a greater or lesser degree dynamic. What I write is not an isolated phenomenon. It is my intentional projection into the continuum where it will meet your intentional projection (however softly focussed) and together we will create… the world.’

‘Let us hope,’ he said, ‘it will be a better world.’

Roger Coward MA, Film Maker, Teacher, Psychotherapist, Author, Musician—and Student—died peacefully at home just before midnight on 20th January this year, nursed to the end by his wife Sandy, with kind and essential support from St David’s Hospice.

It’s easier to believe that his extraordinary journey is not yet over, than it is to accept that he’s left us alone, for now, on ours.

☯

Donations in Roger’s memory can be made to Water Aid or St David’s Hospice Care.