When ads get into our psyche: Materialism and its consequences for people and planet

In this blog, CUSP researcher Dr Amy Isham examines the ways in which advertising moulds our values towards materialism and the consequences this has for us, our children and the planet. This blog first appeared on the Adfree Cities website, as part of the Bad Publicity series.

Blog by AMY ISHAM

Consumer advertising, as a form of media, presents a narrative of what the norms and values of a society are or should be. Typically, consumer advertising tends to present ideas around luxury, status, wealth, and prestige as desirable goals. We should buy a new product because it will make us appear attractive, trendy, or successful. But what happens when people come to believe the messages advertisements tell us, and incorporate these into their own beliefs and value systems?

When this happens, we say that the individual is highly materialistic or holds strong materialistic values. Prof Helga Dittmar, one of the leaders in research on the effect of consumer culture on individuals, defines materialism as: “…individual differences in people’s long-term endorsement of values, goals, and associated beliefs that centre on the importance of acquiring money and possessions that convey status.”

Components of materialism

Highly materialistic individuals therefore consider the pursuit of money and material goods to be a primary life goal, taking importance over more intrinsic pursuits such as quality relationships, helpfulness, and personal growth. Materialistic values are thought of as having three subcomponents (Richins & Dawson, 1992). These subcomponents reflect the extent to which individuals

- grant a lot of attention and importance to the acquisition of material possessions (acquisition centrality),

- view the attainment of material items as the key means by which they can improve their own happiness and life satisfaction (acquisitions as the pursuit of happiness), and

- believe that they should use the ownership of possessions (both number and quality) in order to judge not only their own, but also other people’s success (possessions as defining success).

Advertising and Materialism

Research has consistently shown a positive relationship between exposure to advertising and the strength of materialistic values, especially within children. Analysis of US children and adolescents over several decades highlighted that when a country spent a greater amount on advertising, levels of materialism among youth also tended to be higher (Twenge & Kasser, 2013). Children who are exposed to a greater amount of consumer advertising go on to display stronger materialistic values and a greater desire to purchase the advertised products. This effect is particularly strong when people perceive advertisements to be an accurate portrayal of real life.

What is worrying is that children from less affluent backgrounds appear to be more exposed to consumer advertising, tending to spend more time watching television or living in more urban areas with higher levels of outdoor advertising present. This could mean that they risk developing higher levels of materialism. A study of 9–13-year-olds in the UK (Nairn & Opree, 2021) found that a much greater percentage of deprived (47%) compared to affluent (23%) children agreed that “I would rather spend time buying things than almost anything else.”

How materialism harms us all

So, we know that exposure to advertising can come to influence our individual characteristics by encouraging strong materialistic values. Why do we need to be concerned about this? Well, materialism is bad news, both for people and the planet.

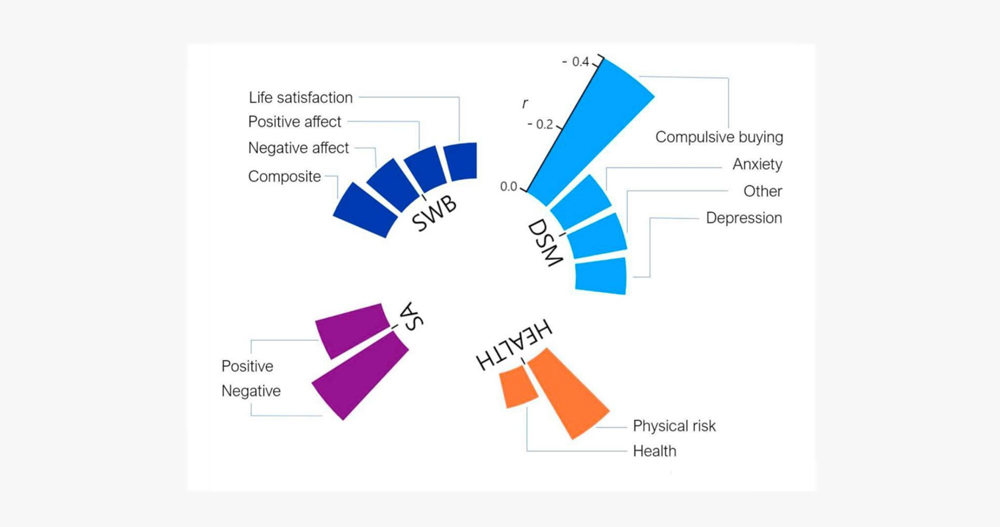

We recently reviewed the evidence around materialistic values and different types of wellbeing (Dittmar & Isham, 2022). What is evident from the increasingly large body of evidence is that materialistic values harm our personal wellbeing, being linked to the experience of more negative emotions, lower self-esteem, symptoms of depression and anxiety, and even poorer physical health, to name just a few. The figure below is taken from our review article and displays the size of the negative effect between materialism and positive wellbeing across different aspects of personal wellbeing.

This negative impact of materialism on wellbeing has been documented across people’s lifespan. Some studies have suggested that the link between materialism and poor wellbeing is stronger for children from deprived backgrounds (Nairn & Opree, 2021), implying that advertising and materialism may promote a process of upward comparisons, whereby those people who do not have the affluent lifestyles that advertising promotes, and materialism desires, come to feel that they do not meet societal standards, hindering their self-esteem.

Materialism doesn’t only cause problems for the person holding the strong materialistic values, it’s also bad for social relationships and the health of the planet. Exposure to materialistic cues such as consumer advertising has been shown to lead to anti-welfare attitudes and less helpful behaviours. People who are more materialistic also care less about environmental issues and engage in fewer sustainable behaviours.

Theories of the nature of human values (Schwartz, 2012) outline how materialism conflicts with values such as universalism (care for the wider world) and benevolence (care for other people), making it difficult for people to be strongly concerned about their own wealth and status whilst also genuinely caring for the wellbeing of other people and the environment. Materialism also harms the environment because highly materialistic individuals place a lot of importance on acquiring material goods and thus are expected to consume more material products. Research documents that materialistic individuals are more likely to engage in both impulsive and compulsive buying. Adfree Cities recently highlighted research documenting that outdoor advertising is particularly well equipped to prompt unplanned purchases.

Pushing back

Just as advertisements work to promote materialism, and thus hinder personal and planetary wellbeing, we can also try to limit their influence. The most obvious and effective way of doing this is to significantly reduce the amount of consumer advertising that people are exposed to, out in public and online. The work of Adfree Cities is invaluable in trying to make this a reality. But if we can’t get rid of advertising, then we can also do better at educating our children about its true intent. Research has shown that families who frequently discuss matters related to advertising and consumption are able to weaken the influence of advertising on children’s materialism (Buijzen & Valkenburg, 2003).

It’s therefore paramount that we challenge advertisers’ messages that money and consumption are the routes to happiness, and instead present alternate visions that foster values and beliefs centred on the importance of individual, collective, and planetary wellbeing.

Key references

Buijzen, M., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2003). The unintended effects of television advertising: A parent-child survey. Communication Research, 30(5), 483-503. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650203256361

Dittmar, H., & Isham, A. (2022). Materialistic value orientation and wellbeing. Current Opinion in Psychology, 101337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101337

Nairn, A., & Opree, S. J. (2021). TV adverts, materialism, and children’s self-esteem: The role of socio-economic status. International Journal of Market Research, 63(2), 161-176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470785320970462

Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 303-316. https://doi.org/10.1086/209304

Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 2307-0919. http://dx.doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1116

Shrum, L. J., Chaplin, L. N., & Lowrey, T. M. (2022). Psychological causes, correlates, and consequences of materialism. Consumer Psychology Review, 5(1), 69-86. https://doi.org/10.1002/arcp.1077

Twenge, J. M., & Kasser, T. (2013). Generational changes in materialism and work centrality, 1976-2007: Associations with temporal changes in societal insecurity and materialistic role modeling. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(7), 883-897. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213484586