A New Climate Movement? Extinction Rebellion’s Activists in Profile | A Report

By Clare Saunders, Brian Doherty and Graeme Hayes

CUSP Working Paper Series | No 25

Compiled by academics at three UK universities, this report presents a profile of participants in Extinction Rebellion’s (XR) mass civil disobedience actions in London in April and October 2019. The report is compiled from three datasets: a protest survey of participants in each of these two XR actions, with 303 short face to face interviews and 232 mailed back questionnaires in total; observational analysis of court hearings of XR activists charged with minor public order offences following the April 2019 action, totalling a further 213 activists; and data from a previous survey of participants in two climate change marches 2009/10, which we use as a benchmark for interpreting our XR survey.

Executive Summary

Extinction Rebellion set out to mobilise a new generation of activists. As our data shows, they have in part succeeded: participants in Extinction Rebellion’s two major actions in London in 2019 had notably little prior experience of protest action, and we encountered many first-time activists. At the same time, however, our socio-demographic profile of XR’s activists in the UK reveals a broadly familiar kind of environmentalist: XR’s activists are typically highly-educated and middle-class (and though our survey did not explicitly ask this, white); they identify politically on the Left; and they consciously adopt multiple pro-environmental behaviours in the course of their everyday lives.

XR’s strength has been to create a new public agency amongst people who are not ‘natural’ protesters, and perhaps even less so natural law-breakers, but who were already persuaded of the rightness of the climate cause, and frustrated with the inability of both ‘politics as usual’ and lifestyle environmentalism to bring about the kind of transformative political change that the climate emergency demands. Mobilising this group enabled XR to significantly expand the numbers of people willing to engage in environmental direct action, broadening its age profile, and bringing non-violent direct action on climate change into the centre of political life in the UK.

The report comes with an Afterword from Sian Vaughan, a first-time Extinction Rebellion activist.

Key Findings

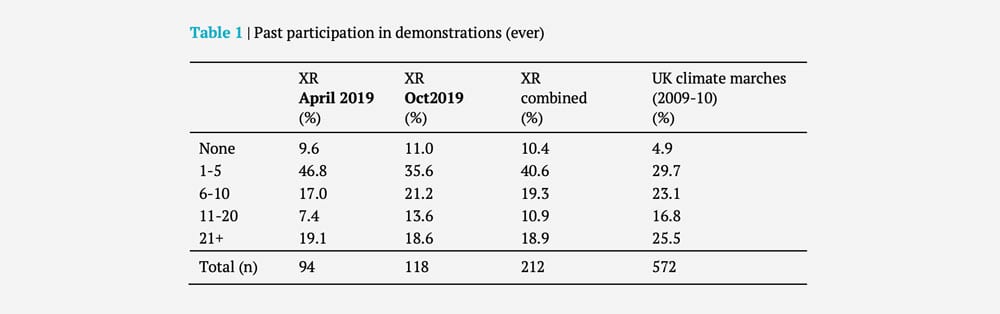

- XR has notably mobilised activists with relatively little prior experience of protest: most participants in XR’s London protests were not highly experienced protesters. In April 2019, nearly three-quarters of our respondents recalled having participated in ten demonstrations or fewer in their lives.

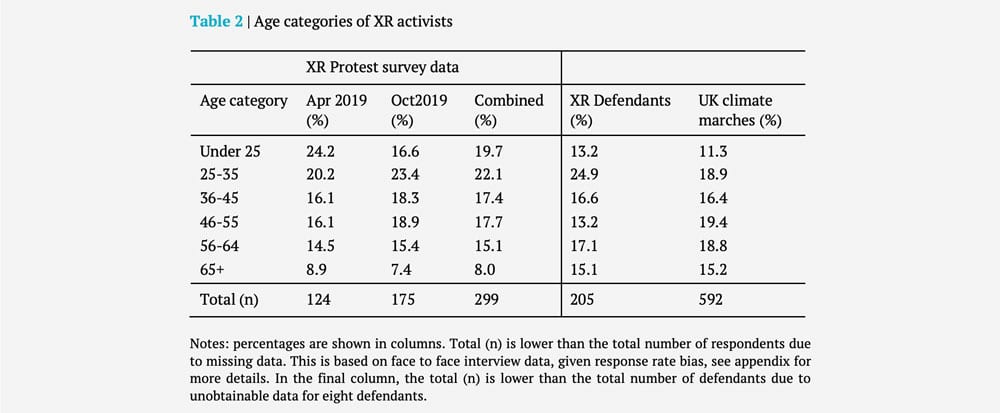

- XR activists have a much broader and more diverse age profile than has been the case for the previously small networks of mainly young activists involved in environmental direct action: in our survey, activists are split almost equally across age categories, except for those over 65, who comprise a smaller proportion of the total.

- The mean age of participants across both actions was 41.1 years old. Under 35s were slightly more numerous in the April London protests than in October (24.2% compared to 16.6%).

- The age profile of those arrested and charged in the April actions is strikingly similar to those surveyed on the streets, though older participants (56 and over) made up a higher proportion of those charged with an offence (32.2%) than those participating in the action as a whole (23.1%).

- In court, older XR activists facing prosecution for civil disobedience spoke of their sense of responsibility to act on behalf of younger generations.

- XR protest participation is highly feminised, with more women than men present in both the major 2019 demonstrations (64.5% in April, and 56.8% in October).

- XR activists are highly educated: 85% hold at least a university (or equivalent level) degree, a figure over twice the national average, with over a third holding a postgraduate degree (Masters or PhD).

- XR activists are predominantly middle-class: around two-thirds of our survey sample self-identify as middle-class (40.9% identified as lower middle-class, and 23.3% as upper middle-class).

- XR’s activists are characterised by high proportions of the self-employed, of part-time workers, and of students, all mainly identifying as middle-class.

- Data on those arrested and charged suggests that participation in these protests was strongly English, southern, and non-metropolitan: over three-quarters of those charged were from below the Severn-Wash line traditionally separating the north and south of England.

- The south-west is a particular focal point for XR activists: just over a third of those charged were from the West Country, with hotspots in Bristol, Frome, Stroud, and Totnes. Southern coastal towns were also well represented amongst defendants.

- By the time of the London October 2019 protest, XR was able to rely on a core of participants who had previously been engaged to a considerable degree in the movement, ranging from involvement in local group activities to previous arrests.

- In only two of the 144 court cases we observed relating to arrests during the April 2019 protest, did protesters have any previous convictions for protest action. However, our survey showed that 12.4% of the participants in the October 2019 protests had previously been arrested for protest.

- Although most XR protesters participated with a group, a higher proportion reported participating alone than is usual for mass protests.

- XR activists are heavily involved in institutional politics as well as protest. They are much more likely to vote and be members of political parties than the general population, but they are also sceptical about the ability of political parties and government to deliver effective solutions to environmental problems.

- XR is a movement of the green left: its activists are primarily supporters of the Green Party, although more of them voted for the Labour Party in 2017 than any other party. We found almost no support among XR activists for the Conservative Party, and very little for the Liberal Democrats.

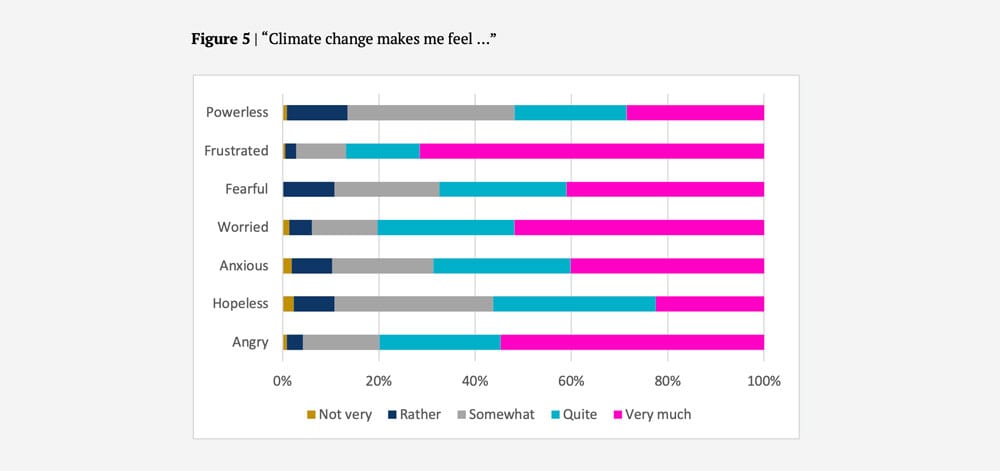

- Frustration, worry, and anger are the most prevalent emotions for XR protesters when asked how they feel about climate change, followed by anxiety and fear. In contrast, powerlessness and hopelessness are the least felt emotions.

- XR protesters have a strong sense of public agency, and do not believe that we can rely on companies and the market, governments, or lifestyle changes by individuals to solve the climate crisis.

- Three motivations are shared by almost all XR protesters—raising awareness of the climate emergency (99%); pressuring politicians to act (99.5%); and acting out of a sense of civic duty and moral responsibility (95.8%). XR activists are much more likely to state that they are motivated to act out of solidarity than out of self-interest.

- XR’s radicalism is underpinned by a strong intergenerational commitment, and driven by a moral obligation to act (for example, see Sian Vaughan’s afterword).

Introduction

Climate activism in the UK was transformed in autumn 2018, when an issue thought by many to be too abstract and scientific to generate widespread social mobilisation went to the top of the news agenda. In large part, this was because of the seemingly sudden emergence of mass grassroots climate protests. A wave of protest started in late summer 2018, when Greta Thunberg launched her school strike for the climate; this lone act of protest had become an international movement involving around 1.6 million by September 2019 (Wahlström et al 2019)[i]. At the same time that Thunberg was sitting outside the Swedish parliament, Extinction Rebellion (henceforth XR), the other major new force in climate activism, and the subject of this report, was preparing its first action campaign: a public declaration of rebellion in London’s Parliament Square on 31 October 2018. This new engagement in grassroots action was undoubtedly spurred by fresh evidence of the worsening impacts of climate change detailed in the IPCC’s Special Report on global temperature warming of 1.5°C, released in October 2018 (IPCC 2018), but there was clearly a constituency ready for a call to action based on ambitious aims and challenging tactics.

Planned by a small group of activists with previous experience in climate and human rights activism and the Occupy movement, XR’s approach fits within a longstanding tradition of transgressive environmental action, but has also proved both novel and unusually potent. It is novel in its emphasis on grief and mass disobedience, its alarmism and its privileging of moral (rather than political) action. It is potent in its capacity to mobilise tens of thousands of people to take illegal disruptive protest action (Doherty, De Moor and Hayes 2018). To achieve this, the group’s founders took inspiration from transformative civil rights movements and, particularly, Chenoweth and Stephan’s (2011) study of civil resistance against authoritarian regimes. Arguing that non-violence is more effective than violence in bringing about societal transformation, and that only a small percentage of the population (3.5%) needs to be actively engaged to create system change,[ii] XR has aimed to inspire mass non-violent civil disobedience to force governments to accede to three demands. These are: 1. Tell the truth about climate change; 2. Achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2025 and halt biodiversity loss; and 3. Create Citizens’ Assemblies to make decisions on a just transition to net zero carbon.

In order to compel political parties and institutions to meet these demands and take emergency action, XR has sought to create economic and civil disruption. Inviting mass arrests plays a central role in the group’s action strategy: XR seeks to ‘overwhelm police resources’ by stretching its operational capacity on the ground, escalating costs, and filling up jail cells; the end goal is to create such disruption that XR will be able to ‘force a political solution’,[iii] or as one of the campaign’s co-founders Roger Hallam put it in February 2019:

The more dramatic the civil disobedience, the better. […] You need enough for the state to have to decide whether to use repression on a mass scale or invite you into the room. […] We’ll give the authorities a fundamental dilemma: ‘Do we allow these people to continue blocking the center [sic] of a global city, or do we arrest thousands of people?’ If they opt for arresting thousands of people, lots of things are going to happen. They will be overwhelmed. (quoted in Hedges 2019)

Mass civil disobedience is XR’s primary strategy, therefore. For Hallam, this means building a new kind of environmental movement which appeals to the right as well as to the left, and recruits participants beyond the ‘usual suspects’ of radical environmental activism:

We must appeal to people who don’t join or support environmental causes, be that because of ideology, social class, culture, religion or race. (Hallam 2019: 49)

XR is particularly intriguing in this respect, as its model of mass disobedience undertaken by ‘ordinary’ members of the public consciously seeks to move beyond the hitherto well-established model of environmental non-violent direct action. This well-established model is based around more or less surprise actions undertaken by small groups of activists, and is typically characterised by strong intra-group ties and inter-personal bonds of mutual trust. Of course, some XR activists continue to work in this way; but moving beyond this model is challenging. One reason for this is that breaking the law, being arrested, charged, and prosecuted, are stressful, time-consuming, and sometimes expensive activities which can have serious consequences for the personal and professional lives of those involved (Sommier, Hayes and Ollitrault 2019), even where the penalties ultimately imposed by the courts are relatively minor (as has typically been the case for XR activists, at least so far). As this statement made in court by a sixty year old former midwife makes clear, for many who were arrested during the XR protests, taking this kind of action was a major step:

My father was a solicitor and I was brought up with great respect for the rule of law. I have never been part of any protest or taken to the streets before Extinction Rebellion.

How typical are first-timer protesters like this new activist among XR participants? In this report, we provide a socio-demographic profile of the activists who participated in XR’s major actions in London in April and October 2019, and of the XR activists who were charged with public order offences for undertaking civil disobedience in the April 2019 action. Focusing on the social and political characteristics of XR’s activists, our report provides an answer to the question of whether XR has, in this sense, succeeded in creating a new kind of environmental movement. Much of the media commentary on XR has focused on individual ‘rebels’, with profiles of retirees, former police officers, and GPs; ‘ordinary’ citizens given space to explain their motivations.[iv] So far, however, these assertions are no more than anecdotes and commentary; there has to date been no comprehensive analysis of participants in XR’s actions.[v] Our report fills this gap.

Our XR data is derived from two datasets: surveys of participants in XR’s two major 2019 actions in London, with 303 face-to-face and 232 mail-back respondents in total; and police and observational court data on XR activists charged with minor public order offences following the April 2019 action, totalling a further 213 individuals. We used standardised protest survey methodology (http://www.protestsurvey.eu/) for the XR protests in London in April 2019 (‘April Rebellion’), and again in October (‘London International Rebellion’). During the protests, we conducted interviews and distributed leaflets with a link to an online questionnaire, with 124 face-to-face interviews and 103 mail-back responses received from protesters in April, and 179 face-to-face interviews and 129 mail-back responses from protesters in October (see the Appendix for fuller details of our methodology).[vi] In order to benchmark this data, we compare it to survey data on previous UK protests, notably two marches on climate change in London in 2009 and 2010 (Saunders et al 2012).

Our police and observational court data concerns XR activists charged under section 14 of the Public Order Act 1986 during the April 2019 protests.[vii] In April, the Metropolitan Police made a total of 1,148 arrests of 1,076 separate individuals during the occupation of four sites in central London (Parliament Square, Marble Arch, Oxford Circus, and Waterloo Bridge).[viii] These protesters were charged in two phases, first in late spring, and then through summer and autumn 2019. We observed court hearings for the second phase, at the City of London Magistrates Court, on seven separate Fridays in August, September, and October 2019, noting details of 144 individual defendants in total, or 17% of the total number of defendants charged in the second phase.[ix] In addition, the Met released to the media the basic identifying data of the 69 activists charged in the first phase, giving us profile information on a total of 213 activists, or 23% of those charged. This tells us their age, their identified gender, where they live, and whether they have prior convictions for participation in direct action. Attendance at the trial hearings also enabled us to collect observational ethnicity data, and to note what proportion of defendants entered a plea of not guilty, and so elected for trial.

Experience of activism

As we noted above, one of the main aims of XR is to mobilise new activists and reach beyond the ‘usual suspects’ of established environmental direct action networks. As Table 1 (below) shows, the evidence from our survey is that XR was at least partially successful in achieving this aim: most participants in the 2019 London actions were not highly experienced protesters, and this was the case for both the April and the October actions. Moreover, they were also comparatively less experienced than our benchmark data drawn from the London climate change demonstrations a decade earlier. Not everyone who participated in XR’s 2019 London actions was there to be arrested; we saw and spoke to many people who were simply there to demonstrate, listen to the speeches and communicate their frustration with government inaction (see Figure 2, page 23). Yet given that the 2009 and 2010 climate change demonstrations were conventional marches, and XR’s 2019 actions were consciously designed around an explicit arrest tactic, if anything we might have expected the 2019 protesters to be more rather than less experienced than 2009/2010 protesters. Our survey data suggests the opposite.

XR protesters had participated in fewer demonstrations previously compared to UK climate marchers (2009-10). Just under one-fifth of XR protesters were ‘stalwarts’: that is to say they had participated in more than 21 demonstrations ‘ever’. Although this proportion is substantial, it is lower than for the two more conventional climate marches surveyed in 2009 and 2010. Further, around 10% of XR protesters were protest ‘novices’, who had never participated in a demonstration before. Surprisingy, this figure was slightly higher in October than in April, and was in both cases around twice the level for the 2009/2010 UK climate marchers. Finally, around half of XR protesters had been on five or fewer protests prior to their participation in the 2019 action at which we surveyed them; at the 2009/20 marches, this figure was much lower, at just over a third.

Socio-demographics of XR protesters

XR protesters are therefore relatively inexperienced. On the face of it, XR appears to have succeeded in one essential part of its strategy: persuading new activists not only to come onto the streets, but also to take part (at least to some extent) in disruptive protest. Does this mean that these activists are in some way different from those we typically find in climate change protests? Can we explain the comparative inexperience of XR protesters by looking at their age profiles?

Age

Our data clearly point to XR as a cross-generational movement. Participants in the London protests spanned a broad range of ages, with close to one-fifth in each of the under 25, 25-35, 36-45, 46-55 and 56-64 age categories, but fewer aged 65 or older (8%, compared to 18.3% of the UK population, ONS August 2019), see Table 2.

There were nonetheless some minor differences in the age distributions across the two separate 2019 London protests. For example, there were proportionally fewer under 25s in October as Table 2 shows. XR protesters were on average younger, especially in April, than demonstrators surveyed on the annual climate marches in 2009 and 2010. But as we have noted, there is a key difference between these demonstrations: the 2009/10 actions were conventional marches, while the XR actions were designed to be disruptive.

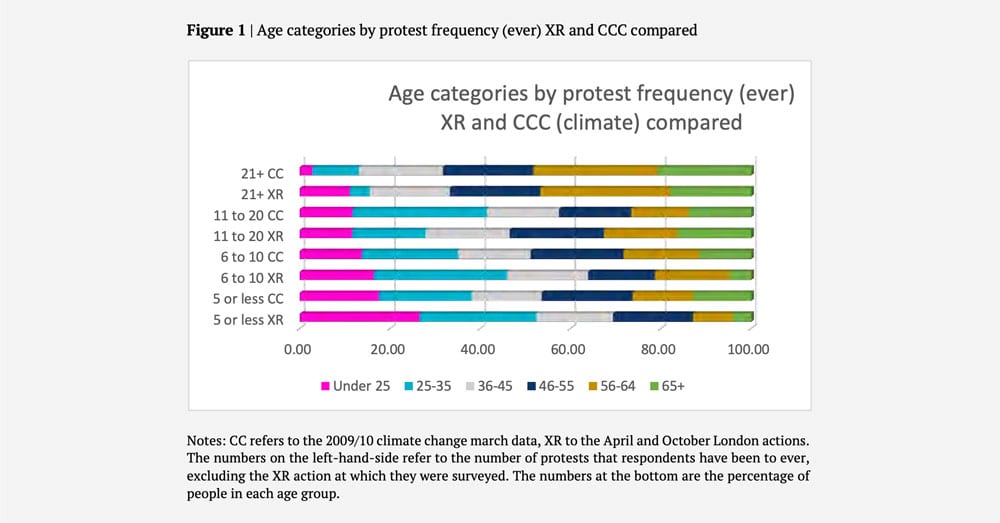

Does this help explain our findings about inexperience? Figure 1 shows, in general, that there is an age effect at work: the younger protesters are, the less likely they are to be experienced protesters. This holds both for our XR survey, and for our benchmark 2009/10 climate change march survey data. But the effect is stronger for XR protesters: just over half of the XR protesters who had participated in 5 or fewer demonstrations were aged 35 or younger, compared to 38% of the 2009/10 protesters. What we have not captured in Figure 1 is the striking fact that nine of every 10 of the XR protesters aged 35 or younger had participated in protest five times or fewer; and all of them had participated ten times or fewer. In the 2009/10 climate change march survey data only half were relative novices (participating 5 or fewer times) and more than one-fifth had participated at least 11 times. This suggests that XR’s mobilisation of relative protest novices can, at least to some extent, be explained as a youth effect.

Yet our data also show that older participants played a key role in the character of the XR actions. Here, it is significant that that age profile of XR arrestees (‘Defendants’, in Table 2, above) was older than those we surveyed on the street. Of those arrested and charged in the April actions, the youngest age group is slightly under-represented, compared to all those on the streets; whilst the over 65s are significantly over-represented in the courts, which corresponds to XR’s strong commitment to intergenerational responsibility. In numerous mitigating statements given in court after pleading guilty, older defendants spoke of their sense of obligation to younger generations, sometimes including their own grandchildren. As one woman, born in 1942, said:

I am a mother and a grandmother and a great grandmother […]. As part of the generation whose complacency has led to this emergency, I should prepare to be arrested. I couldn’t in conscience stand aside in the face of the threats that confront us all.

For another, born in 1944:

As retired adults we should act on behalf of young people and schoolchildren who cannot risk criminal records. (Both quoted from court hearings of 23 August 2019)

In a period when political differences between generations are discussed often, XR has clearly succeeded in appealing across generational divides. Whilst this is similar to previous climate change marches, it also makes it distinct from other environmental direct action movements in the UK. Studies have shown that direct action environmental activists are mainly young adults, whether in the anti-roads movement of the 1990s (Seel et al 2000; Wall 1999), or in more recent cases such as the Camp for Climate Action (Saunders 2012).

Education and Class

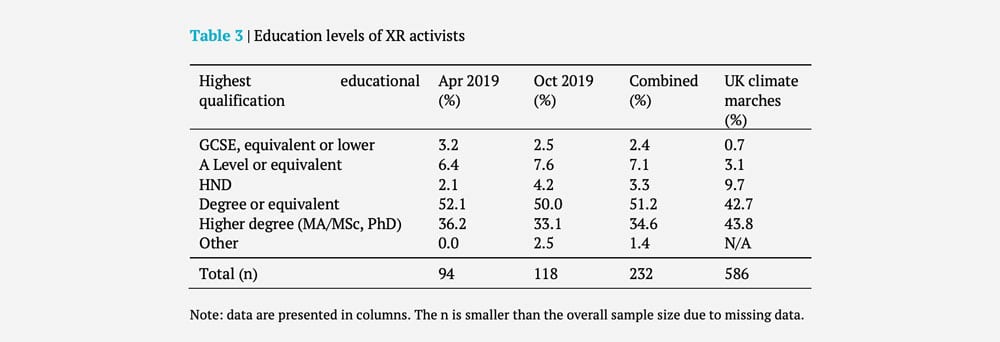

Despite our finding of the relative inexperience of the participants in the 2019 actions, our protest survey data also tells a rather more familiar story about XR’s activists. Our survey reveals that a striking number of XR activists are highly educated, to degree level or higher. In the UK, 42% of the population aged 21-64 have university-level educational qualifications (ONS 2018). But among XR participants, the proportion of those educated to degree level is more than twice the UK average: across both our surveys, 85.8% of respondents say they had at least a degree or equivalent qualification (or were studying for one), with over a third (34.6%) telling us that they hold a postgraduate degree. As striking as these figures are, they were both consistent across our April and October survey data, with few differences between the two, and with the 2009/2010 climate marches data, see Table 3, below.

Indeed, the high education levels of the 2019 XR participants and the 2009/2010 climate march participants are startlingly similar (with 85.8% and 86.5% having at least a bachelor’s degree). Remarkably, high levels of education are consistent across all age categories. Approximately half of the respondents across all age groups have a degree, with approximately another 40% in all age groups over 25 years of age also having a postgraduate degree (compared to only 8% of those under 25, which can be explained by age effects).

Given that access to higher education in the UK is strongly correlated with class position, does the implication that XR protesters are from the middle classes ring true? In order to get an understanding of the social class of XR participants, we use self-identification rather than a measure based on occupation.[x] To the extent that they identify with any social class, XR participants identify as middle-class, with around two-thirds of participants placing themselves in this class (40.9% lower middle class, and 23.3% upper middle class; aggregated sample for both mobilisations). Slightly fewer than 10% overall see themselves as working-class (9.8%), and a very small minority (around 1% for both mobilisations) identify as upper-class. However, this only accounts for three-quarters of our sample; of the rest, 14.0% of respondents identify as ‘none’ when asked about their class, whilst a further 10.9% say they ‘don’t know’ to which social class they belong. This subjective class position is similar to the profile of respondents to the 2009/10 climate change march surveys, but it contrasts with general population surveys for the UK, in which more people identify as ‘working class’ (51%) than middle class (39%), while 1% of Britons consider themselves upper class, and the remainder don’t know (Smith 2019).

Whilst measurements of class are inherently controversial (a self-identification measure is very different from the National Readership Survey’s (NRS) social grading methods in which the profession of the highest income earner in a household is often used as a proxy for class), our sample provides evidence that XR participants are substantially more likely to see themselves as middle-class then the UK population as a whole. Regarding XR protesters’ employment situation, many more are self-employed (24.5%, compared to 15% in the UK overall, ONS 2019), retired (18.1%) or in full- or part-time work (both 17.1%) than any other category; 9.9% are in education, 4.6% are unemployed (compared to 3.8% in the UK overall—ONS 2019) and 0.9% are housewives or househusbands.

As noted above, there are some differences in age distributions across the two XR London actions. This is very likely reflected in the lower proportion of students who participated in October compared to April; the overall finding that 9.9% of XR respondents are currently in education hides a sharp contrast between 14.7% of April respondents and 6.2% of October respondents. Lower rates of student participation in October might be attributed to the demands on student time during term-time. In October, the lower proportion of students is compensated for by significantly higher numbers of retirees. Otherwise, there is consistency in the class identities and employment status of XR participants at the two different points in time. On the one hand, XR is not a movement of the economically marginalised; but on the other, there are high proportions of the self-employed, of part-time workers, and of students, all mainly identifying as middle-class. For different reasons, these groups are more likely than others to enjoy some autonomy and flexibility over their use of time, facilitating their engagement in protest. In the social movements literature, this is known as an effect of biographical availability (McAdam 1990).

In this way, XR activists therefore reflect the traditional typical profile of environmental activists: they are highly educated, and employed in fields such as education, health, welfare, and the creative professions,[xi] which are relatively distant from finance and corporate capitalism (Cotgrove and Duff 1980: 344; Doherty 2002: 57-63).

Where do XR protesters come from?

The majority of respondents to our protest survey (56.2%) spent more than 90 minutes travelling to get to the protest actions in London; 37.1% took between 30 minutes and an hour; but only 6.7% say that they had taken less than 30 minutes. This suggests that the majority of participants were willing to invest significant time and resources to attend. The data on those charged following the April protests provides a clearer picture of the home locations of the arrested defendants. They come predominantly from the south of England: of the 197 defendants for whom we were able to ascertain home addresses, over three-quarters (77.7%) were from below the Severn-Wash line traditionally separating the north and south of England, with the remaining defendants split between England above the Severn-Wash (12.7%), Wales (6.1%), Scotland (2%), and outside the UK (1.5%).

Within the court data, two patterns are apparent. First, whilst London was strongly represented (16.8% of all defendants, or 33/197), large urban areas outside London were under-represented, with only 13 (6.6%) defendants from Birmingham, Greater Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Bradford, Sheffield, Newcastle, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Swansea, and Cardiff combined. In contrast, southern coastal towns and cities are strongly represented: defendants came from Cromer, Leigh on Sea, Ramsgate, Brighton, Worthing, Bournemouth, Plymouth and St Ives. Most strikingly, just over a third (34%, 67/197) are from the West Country, with hotspots in Bristol, Frome, Stroud, and Totnes in particular. These geographical factors point probably to the importance of local cultural networks to both participation (in general) and to the acceptance of civil disobedience (in particular), particularly the Transition Towns and Flatpack Democracy networks, which are strong in the south-west (see below for more data on overlaps between XR and Transition Towns).

Participation in the XR London protests was therefore strongly English and southern, with a strong non-metropolitan character. Since there were separate XR protests in Cardiff, Manchester, Leeds, and Glasgow during the summer of 2019, the southern bias of participants in the London events does not perhaps tell the whole story. However, XR clearly focused its mobilisation on the two London rebellions; even the week-long ‘Northern rebellion’ in Deansgate, Manchester in late August 2019 was presented primarily as a rehearsal for the October ‘International Rebellion’ in London. The strong presence in London from the towns of the south-west and south coast compared to major cities seems to indicate the areas where XR has its strongest support.

Ethnicity

Our protest survey data confirms the impression from court data that those protesting in London were overwhelmingly British, even if their families are somewhat more cosmopolitan: 83.7% were born in the UK, and 99% live in the UK, although fewer—79% –have a primary parent (mother if known) from the UK. In contrast, 7.1% of participants were born in European countries, and 9.3% further afield; 12.3% have a European primary parent, and 9.7% have a parent from elsewhere in the world. Although we did not collect data about ethnicity, of the 132 defendants we were able to observe in court,[xii] all but two were white.

A larger dataset on the self-defined ethnicity of 1,143 XR arrestees from the April London protests, provided by the Metropolitan Police (following a Freedom of Information request), shows a broadly similar picture. Here, 1,032 arrested activists identified as White (90.3%), whilst a further 54 (4.7%) did not state their ethnicity. Of the remaining 5%, 11 identified as Asian (1%), 5 as Black (0.4%), 31 as Mixed (2.7%), and 10 as Other (0.9%).[xiii] For reference, 86% of the population of England and Wales identified as White in the 2011 census, 7.5% as Asian, 3.3% as Black, 2.2% as Mixed, and 1% as Other (gov.uk 2018).

If XR has to a certain extent succeeded in recruiting new activists, the data from its London actions suggests that it has not done so from outside the highly educated, white, middle-class constituency which has long been characteristic of the environmental movement in the UK.

Gender

We also noted a familiar pattern in the gender profile of XR protesters. On the streets, a higher proportion of women compared to men were present in both XR actions, most notably so at the April 2019 blockades (64.5% women, compared to 56.8% in October, according to self-identification data in our survey; only one survey respondent—in October—identified as being from a gender other than male or female, although seven of our face-to-face interviewees identified as ‘other’). This predominance of women is a feature shared with the school climate strike movement (Wahlström et al 2019), as well as the ‘American resistance’ protests of 2017 (Fisher 2019); and it was also a notable feature of the 2009/2010 climate marchers in the UK.

We did, however, note differences in the gender profile of those we surveyed on the streets compared to those for whom we have police and observational court data. Amongst those arrested and charged in April, our data on gender is observational only (in court, defendants are not asked to self-identify, or to confirm, their gender). Here, men are in the majority, making up 53.1% of those charged (n= 213), with women making up the remaining 46.9%. Amongst those we observed entering pleas (n=139), there is a broadly even split between men and women for those pleading guilty (men: 51.1%; women, 48.9%; n=94). For those pleading not guilty (n=45), the difference is more acute, with men constituting 62.2% of this group, and women 37.8%. The relatively small numbers for whom we have data mean that any conclusions we can draw are inevitably tentative, but it seems that men in XR are both slightly more likely than women to be arrested and charged, and subsequently to plead not guilty (and thus elect to go to trial). Of the 45 who pleaded not guilty, 17 were women and 28 were men. Whilst gendered differences between arrests and protest participation may be explained by either activist behaviours or policing decisions, the greater willingness of men to plead not guilty is more likely to be explained by structural or cultural factors. For instance, men are likely to have fewer caring responsibilities and therefore greater willingness to spend more time in the courts.

Social networks, activist experience, and organisational memberships

The importance of recruitment via social networks is very strongly recognised in existing literature about social movements. Involvement in social networks provides people with social capital (Putnam 1993); increases their ‘structural availability’ (Cable 1992, Schussman and Soule 2005, Saunders et al 2012); socialises them into movement activities; and enables them to develop activist identities (Johnston and Larana 1994). We may consider this to be particularly important where activism involves a significant degree of risk, such as arrest and imprisonment. For those working with children, or in the care sector, the consequences of even a conditional discharge are serious for DBS checks and thus for continuing or future employment. We might therefore expect XR’s activism to require the type of ongoing support, solidarity, and understanding that social and organisational networks can provide.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, therefore, over two-thirds (69.2%) of those we surveyed in October say that they had been involved in XR or in XR-related actions prior to the October ‘Rebellion’. Around one in ten (9.2%) had participated in the November 2018 London Bridge blockades, and just over three in ten (31.5%) had participated in the April 2019 action. Moreover, the vast majority (85.4%) were participants in XR local groups, and most of that sub-group had previously participated in actions organised by their group (69.3% of all October respondents). By October, therefore, XR was able to rely on a core of participants who had previously been engaged to a considerable degree in the movement, ranging from involvement in local group activities to previous arrests. For a movement launched the previous year, this is a significant indicator of the rapid development of a core of committed activists.

One in eight (12.4%), indeed, told us in October that they had previously been arrested for protesting. We did not collect data on previous XR participation in the April survey so cannot compare across the two datasets; but in our court data there was little evidence of activists having previous convictions for involvement in protest (which would typically be for criminal damage, or public order offences such as obstruction of the highway, or aggravated trespass). In 94 of the 144 individual hearings we witnessed, the defendants pleaded guilty, and prior convictions were discussed in court; only two defendants had prior convictions for this type of relevant offence, and only a handful had prior convictions or cautions of any kind. The typical activist arrested and charged in the April mobilisations, at least, did not fit the profile of the experienced, ‘disobedient’, activist.

Given that the 2019 XR mobilisations are on a scale previously not witnessed in UK environmental direct action, this is perhaps unsurprising. But there are further peculiarities of XR’s mobilisation. At the first set of court hearings we attended (23 August), we witnessed two defendants recognise each other, and chat briefly in the waiting room: they first met each other in the police van, after they were arrested (20 April, Oxford Circus). Three weeks later (13 September), two defendants—a man and a woman, each in their mid-50s, one from Brighton, one from Sutton in Surrey—expressed surprise as the police body camera footage of the woman’s arrest on 21 April was played in court; the pair then realised that they were sitting next to each other in the roadway in Parliament Square when they were arrested; they hugged, a little awkwardly. Arrested together and prosecuted together, they were nonetheless perfect strangers.

The wider data from the survey points to a striking feature of climate change mobilisations: around one-fifth of participants (in both XR actions, as well as in the 2009/10 climate marches) claim to have participated alone. This is a relatively high figure; Wahlström and Wennerhag (2014) found, across 69 European demonstrations, that on average as few as 7.2% of protesters attended alone and were also not asked by anyone to attend. Relatively low numbers in the XR protests participated with friends (43.1%), acquaintances (25.5%), their partner (27.8%), and fellow members of an organisation (32.9%). More striking still, personal contacts do not appear to be particularly strong as channels for mobilisation: only 19% of respondents claim that someone specifically asked them to take part in the protest, although 52% of them specifically asked someone else to participate.

We also noticed that many defendants attended the court hearings on their own, without visible support from a local group. This may be in part because the charges were in almost all cases relatively minor, whilst XR’s mass arrest strategy may have had the effect of making a magistrates’ court hearing appear relatively routine. Yet numerous defendants gave heartfelt and sometimes highly emotional statements about what had driven them to break the law, with many in tears as they did so. There was an overwhelming sense that these are significant and symbolic moments for the defendants themselves.

Whilst there were always others from XR present in support on these occasions, and also XR ‘wellbeing’ teams who waited outside police stations to look after arrestees when they were released, it was clear that in many cases the defendants had not previously met these support groups. The London protests, therefore, included a significant minority of participants who acted at least partly on their own, inspired by the general message of XR, and also many who went through the courts without direct support from other activists they already knew. This is unusual in the history of high-risk forms of activism such as civil disobedience, where strong ties with fellow activists have been seen as crucial to developing commitment (McAdam 1990).

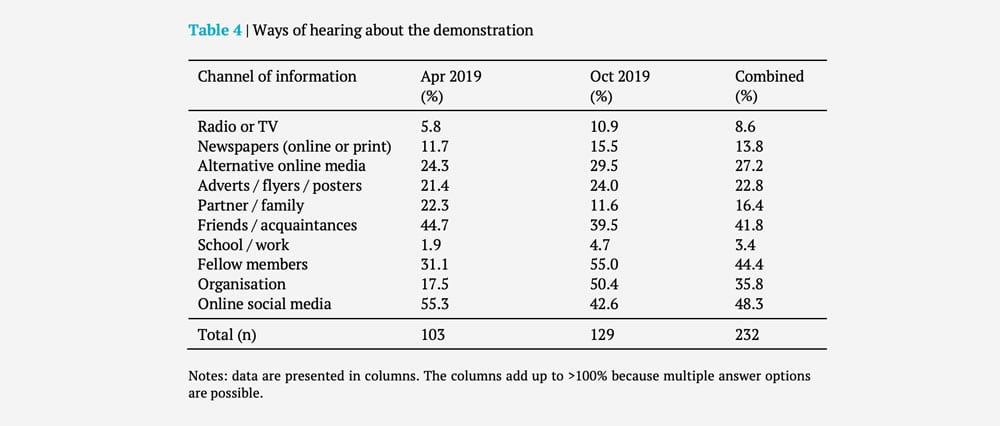

Clearly, by October 2019, attempts to raise awareness of XR actions via conventional media channels had paid off. Notably more of our protest survey respondents had found out about the XR demonstrations through TV, radio, and newspapers in October compared to April. But the most popularly checked sources for finding out about the demonstration were social media in April (55.3%) and fellow members in October (55.0%); in contrast, social media was less frequently mentioned in October (42.6%) as were, markedly so, fellow members in April (31.1%) (Table 4, below).

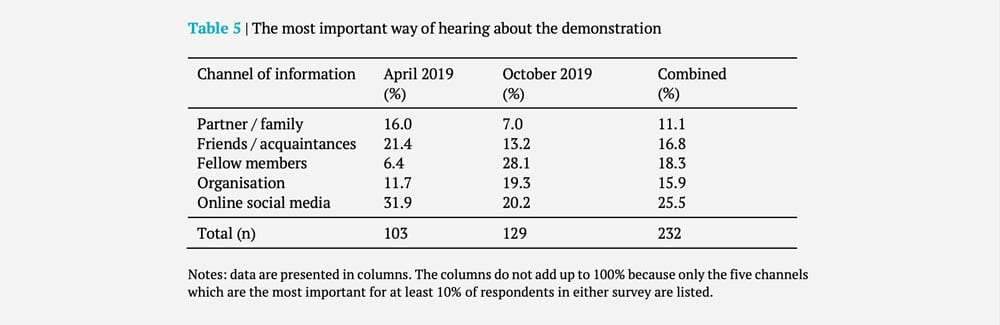

We also asked respondents to tell us which of these ways of hearing about the demonstration listed in Table 4, above, were the most important for them. Here, as Table 5 (below) demonstrates, only five of the ten channels of information were categorised as the most important channels of information by at least 10% of respondents. These are social media (31.9% in April, 20.2% in October), friends (21.4% in April, 13.2% in October), partner/family (16% in April, 7% in October), an organisation (11.7% in April, 19.3% in October) and fellow members (6.4% in April, 28.1% in October).

These varying figures suggest a marked recruitment shift from April, when personal networks and related social media were much more important than organisational ties (69.3% vs 18.1% combined), to October, when organisational ties were much more important, if still not dominant (37.4%, vs 40.4% for personal ties and social media). We suggest two possible reasons for this shift. First, the changes in the relative importance of channels away from social media and towards other members might be representative of the changing demographic, as fewer young people participated in October. Second, by October XR had solidified its grassroots organisation, leading to stronger ties and better networking among its participants. Tables 4 and 5 therefore suggest that the development of local organisational capacity across 2019 helped XR participants hear about and participate in XR actions with fellow activists (a phenomenon known as meso-mobilisation; see Gerhards and Rucht 1992), particularly in October.

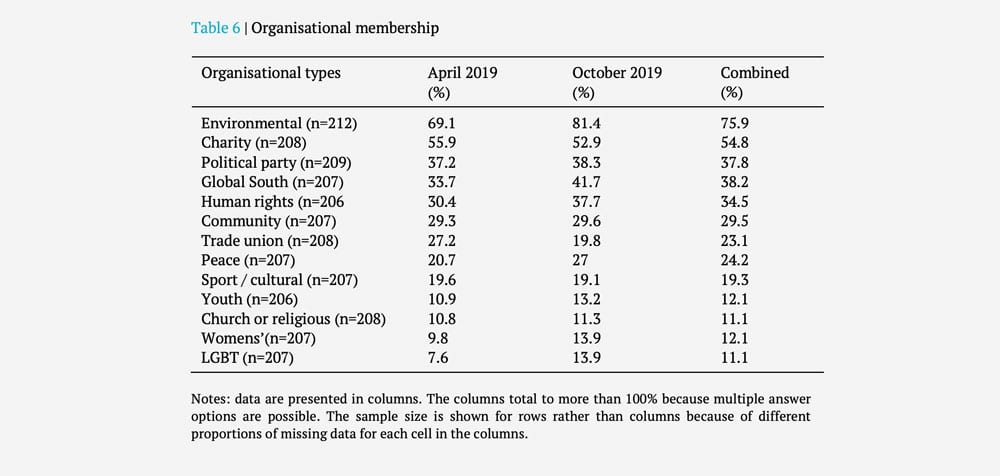

Given the importance of organisations and fellow members as channels for hearing about the XR actions, it is important to examine the other organisations to which XR activists belonged to at the two points in time. In general, organisational membership is higher across multiple sectors in October compared to April (Table 6, below).

The increase in organisational membership is particularly acute for environmental organisations (up from 69.1% in April to 81.4% in October), ‘Global South’ organisations (from 33.7% up to 41.7%), peace organisations (20.7% compared to 27%), women’s organisations (up to 13.9% from 9.8%) and LGBT organisations (13.9% compared to 7.6%). These differences are likely to reflect the older age profile of the respondents to the mail-back survey. Older generations are more likely to participate in politics collectively through organisations (Whiteley, Pattie and Seyd 2004); and although trade union membership seems to be an exception to this, as it is lower in October (19.8%) than in April (27.2%), this is also most likely partly a consequence of the higher numbers of retirees in October.

For the October Rebellion only, the protest survey also asked XR participants if they had ever previously been a member of a range of environmental and related organisations. The relatively high responses for Transition Towns (25.0%), the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (27.6%), Amnesty International (45.9%), Friends of the Earth (47.3%), and Greenpeace (54.4%) suggest a tradition of participation in related campaigns amongst XR activists. While the highest figures are for Greenpeace, Amnesty, and FoE, possibly most important are the numbers for CND and Transition Towns because there may be a route from these organisations to XR’s repertoire of action. CND had its highpoint of membership in the 1980s (Maguire 1993) but has the strongest association with XR’s tactics of mass civil disobedience of any British campaign organisation. Meanwhile, the Transition Town movement, although not now as prominent as it was in the first decade of the 2000s, was strongest in south-west England, consistent with our data on XR’s strongest concentration of activism; and it has a strategy of creating positive practical alternatives locally rather than focusing on systemic political critique (Kenis 2016). Although both CND and Transition Towns have different aims to XR, it is not surprising to find that XR has recruited from, and is potentially strongly influenced by, those with past experience in both.

Political engagement, trust and allegiances

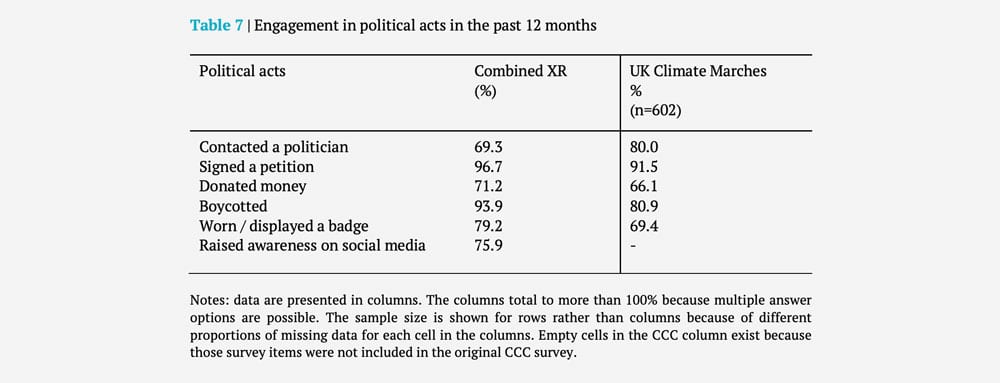

XR claims to be ‘beyond politics’, and is highly critical of what it calls the main political parties’ ‘business as usual’ approach to climate change. Indeed, controversially, XR chose not to endorse any parties or candidates in the 2019 December general election. XR activists staged ‘bee’ actions (in which activists dressed as bees glued themselves to the parties’ campaign buses, because they are ‘bee-yond politics’) against the Labour, Liberal Democrat, and Conservative campaigns,[xiv] despite the significant manifesto differences between the parties. Nonetheless, our protest survey evidence indicates that participants in XR’s April and October actions appear to have extraordinarily high rates of political engagement, including with political parties (over a third are members of a political party, Table 7), and they are generally interested in politics: in response to our survey questions, 80.9% in April and 88.8% in October say they were ‘quite’ or ‘very’ interested in politics.

The vast majority of our respondents claimed to have voted in the May 2017 general election (82.8% in April, 88.1% in October). These figures appear high, but they are underplayed given that that 14.0% of April respondents and 9.3% of October respondents claimed to be ineligible to vote in 2017. These figures point to a level of electoral participation which is much higher than the UK average (voter turnout at the 2017 general election was 68.7%). Further, XR participants’ high levels of electoral engagement do not appear to mask a wider disaffection with UK parliamentary politics: only a small minority ‘strongly agreed’ or ‘agreed’ that ‘I don’t see the use of voting, parties do whatever they want anyway’ (12.9% in April and 16.4% in October), even if there are high levels of distrust in political institutions, more generally.

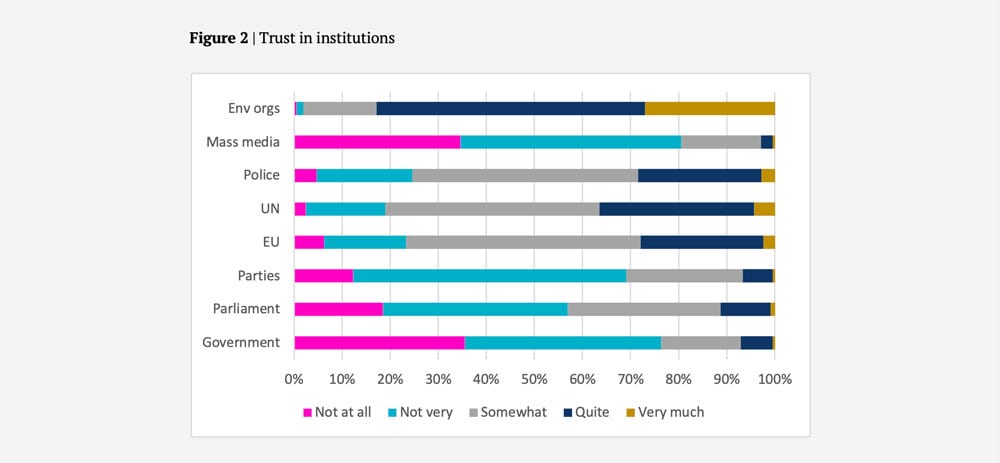

As Figure 2 shows, XR participants, in general, have low levels of trust in government, established mass media, parliament, and political parties. They are somewhat trusting of the police, but markedly more trusting of international institutions such as the EU and UN. They trust environmental organisations the most, although up to 10% are sceptical even of environmental organisations (Figure 2). In tune with the lack of trust for parliament and parties, 74.2% agree or strongly agree that ‘most politicians make a lot of promises but do not actually do anything’.

As noted above, a central principle of XR is that it is beyond politics. But it is not always clear if this just means ‘beyond party politics’, as it is sometimes phrased in XR communications, or whether it is meant to define a position outside the political institutions, or whether it means being ‘above’ ideology. Whilst XR is clearly making political demands on government, its founders have also explicitly aimed to appeal to a constituency of citizens beyond the common left-environmentalist constituency, as we noted (see Hallam 2019). However, if this is the aim, it is not reflected in the political allegiances of the activists who took part in the London protests.

Indeed, the majority of XR respondents claim to most closely identify with the Green Party (59.1%), followed by Labour (15.5%), and the Liberal Democrats (3.9%). Across both surveys, only one participant claims to most closely identify with the Conservative Party, and only two respondents (1.1%) say they had voted Conservative in the 2017 general election. Whilst many of those who closely identify with the Green Party had supported it in the 2017 general election (33.7% of our respondents voted Green in 2017), Labour was the most voted for party (by 47.2% of respondents).

XR’s activists are therefore primarily supporters of the Green Party, but more of them vote for the Labour Party, very likely because of the first past the post voting system. There is almost no support for the Conservatives or any other parties of the right, and very little support for the Liberal Democrats. XR is therefore clearly a movement of the left, and it will likely find it difficult to engage with the Conservative majority government.

As we saw at the beginning of this report, most XR participants were not highly experienced protesters, but what about their broader political engagement? Typically, those who take to the streets to air their political grievances engage in both electoral and protest politics (Saunders 2014). As shown in Table 7, XR participants engage frequently in a range of political acts as do UK climate marchers (2009/10).

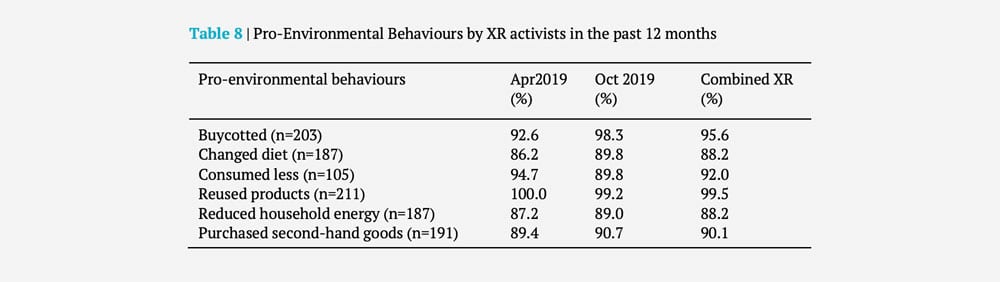

As might be expected, XR participants have high levels of engagement in pro-environmental behaviour (Table 8). We do not have comparable data at the national level, from other protest surveys, on pro-environmental behaviour; but much of the commentary hostile to XR focused on the supposed hypocrisy of XR activists and supporters. For example, whilst the Prime Minister referred, with typical provocation, to XR as ‘uncooperative crusties’ in ‘heaving hemp-smelling bivouacs’,[xv] right-wing media and politicians generally focused on what they saw as the hypocrisy of XR activists and celebrity supporters,[xvi] and used ‘middle-class’ to suggest dismissively that its politics could be explained by its social base.[xvii] Given these attacks, the non-uniformity in affirmative answers to questions about participation in pro-environmental behaviour may indicate a certain resilience among XR protesters to the relentless focus of critics on their personal conduct, as if any individual ‘lapse’ disproved their wider arguments.

These kinds of attacks were probably expected by XR. What is interesting in this respect is that activists appearing in court consistently gave accounts of how they had moved towards civil disobedience once they realised that changing their own patterns of consumption was ineffective. They stated that only political action by governments would bring about the major changes needed to avert climate catastrophe. As one 40 year old woman put it in court, when pleading guilty:

I recycle obsessively, refill my water bottle, no longer eat meat, I’ve signed multiple petitions and written to my MP, stopped my 15 year career working in retail marketing, and I have not had children. All of these actions have had no effect.

The political engagement of XR activists thus combines above average levels of voting and membership of political parties, with high engagement in pro-environmental behaviours, participation in disruptive protest and high levels of scepticism about the ability of political parties and government to deliver solutions. Whilst XR activists are overwhelmingly committed to taking responsibility for their own personal consumption, as the quote above illustrates, and as we further illustrate below, they are sanguine about the impact lifestyle change will have on preventing climate breakdown.

Climate Breakdown: Diagnosis and Prognosis

In its statement of values, XR seeks to balance challenging what it defines as a ‘toxic system’, including the profit-driven neoliberal economy, with an avoidance of personal attacks (Principle 8, ‘we avoid blaming and shaming’).[xviii] In other words, a critical view of institutions and practices need not mean a focus on individuals as personally responsible. This is quite a complex position to ask activists to adhere to; what can we discern from our protest surveys regarding who or what XR activists think is to blame for the environmental crisis? In their answers to an open question on this, respondents were consistent with XR’s principles: they overwhelmingly wrote about fossil fuel companies, greed, and capitalism. A 60-year old woman, who took part in the October ‘Rebellion’, for instance, wrote that she blamed ‘fossil fuel industries, greedy capitalists and disregard for people in developing countries’.

We also asked XR protesters about who, or what, is best placed to solve our environmental problems, using answer options common to surveys of climate protestsNone of the options offered were strongly supported by XR respondents. Although they were more positive about science than government, companies and the market, and individual lifestyle changes, only 41.1% of XR protest survey respondents agree that we can rely on science to any degree (see Figure 3, below). Companies and the market are trusted the least (88.5% disagreed or strongly disagreed that companies and the markets can solve our environmental problems, whilst 86.6% disagreed or strongly disagreed that we can rely on government to solve environmental problems). This seems to be a potential point of contention for XR: its strategy emphasises lobbying the government for action, but its activists do not think the government can deliver. The answer to this tension may lie in XR’s third demand, that decisions on the transition to net zero carbon be taken by citizens’ assemblies based on popular sortition (the random selection of participants, chosen to be representative of the population in general).

With regards to specific measures, there was a mix of answers to qualitative questions: some want the government to act to cut emissions, others wrote more specifically about the need to decarbonise the economy and invest in renewables. Some talked about a transition to a more respectful society, reflecting XR’s support for ‘regenerative culture’, whereas others called for a deeper and more urgent structural transformation—as a 23-year-old woman participant put it, ‘Radical, immediate and COMPLETE system change’ (emphasis in her original answer).

![Figure 3 | Percentage of XR respondents (dis)agreeing with the statement “To what extent do you agree that [each of the following] can be relied on to solve our environmental problems?”](https://cusp.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/Fig-3-2.jpg)

Motivations and emotions

In their answers to open questions in the survey about why they decided to participate in the XR actions, activists gave a variety of reasons, including the urgency of the situation, the need to make the government stand up and act, belief in personal and group efficacy, and moral obligation. In relation to urgency, one 32 year-old woman told us that she participated:

because all the less disruptive forms of campaigning have failed and we have basically run out of time to prevent climate breakdown and the human and animal suffering that will be caused by this.

A retired participant with no dependents told us that they:

have no reason to worry about the effects of a possible criminal record. Also, because I have been around since before climate change was first mooted as a problem and have been largely unaware of the emergency our lifestyle was bringing on.

Some wrote about existential threats, the likelihood of human extinction, and out of control degradation of the planet. In a statement stressing the need for government to act, a 23 year-old woman wrote:

Because I believe that the environment and our planet’s future should be the UK government, and the international community’s, top priority.

In relation to efficacy, many participants expressed their wish to, or belief that they could, be effective:

I agree with the 3 key aims of XR and want to make a difference. (59 year-old man)

collective action is most likely to be effective. (66 year-old man)

I want to help save the planet and have given my support to a movement I believe could bring about that change. (26 year-old woman)

Answers to closed survey questions also show XR participants’ strong belief in their ability—as individuals or organised groups—to influence positive change. Over 70% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that ‘my participation can have an impact on public policy in this country’; more than 80% agreed that ‘organised groups can have a lot of impact’; and the same proportion believed that ‘if citizens from different countries join forces, they can have a lot of impact on international policies’.

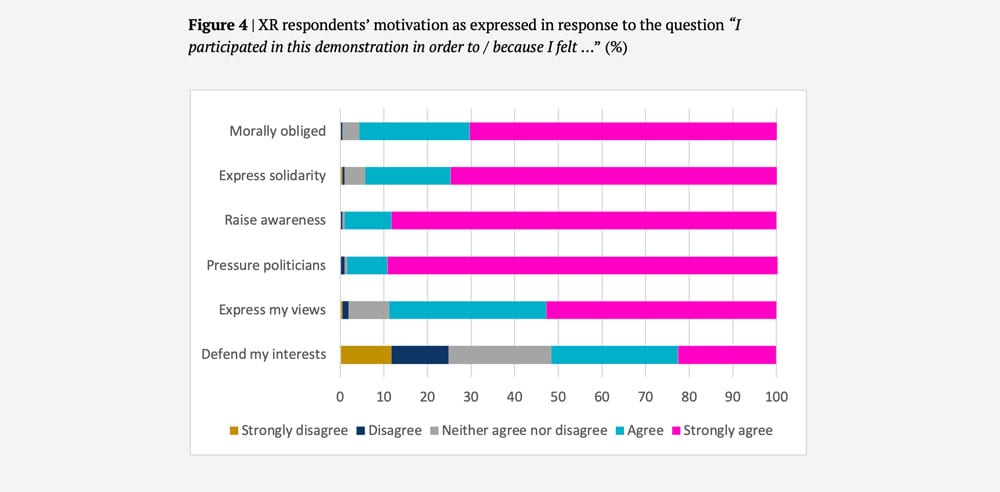

These answers reflected a strong belief among participants that their action had a strong instrumental purpose: for example, 99.0% agreed or strongly agreed that they were motivated to participate in the actions in order to ‘raise awareness’, and 99.5% to ‘pressure politicians’, Figure 4, below. But respondents also underlined that their participation stemmed from a wider sense of civic duty, with 95.8% agreeing or strongly agreeing that they felt ‘morally obliged’ to participate in the action. For one participant, a 34 year-old man, ‘As someone aware of the issues we’re facing I felt I was morally obliged’; others referred to their moral obligation to future generations, with one 58 year-old woman citing the familiar phrase: ‘If not me, then who? If not now, then when?’.

In general, these answers demonstrate strong support for a range of standard motivations for political protest: the vast majority agree that they are participating as a means of raising awareness, followed by pressuring politicians, feeling morally obliged, expressing solidarity, and defending their interests. Self-interest is the least agreed with motivation; even here, however, more than half agreed that this was also a reason explaining their participation. Some XR participants therefore believe they are acting in their own interest—but this number remains much lower than ‘expressing solidarity’. Clearly, therefore, XR participants are acting for others as well as (or perhaps more accurately, rather than) just themselves.

The nature of this interest is more clearly identifiable in our respondents’ answers to our next question. More than other environmental groups, XR has encouraged its activists to express their emotions, particularly their grief about the damage caused by climate change; and Figure 5 (below) shows how the issue resonates emotionally with participants. Frustration, worry, and anger are the most prevalent emotions, followed by anxiety and fear. In contrast, powerlessness and hopelessness are the least felt emotions, suggesting that participation expresses a sense of public agency, although even here a majority of participants did feel ‘quite’ or ‘very much’ affected.

Conclusions

Our report shows that Extinction Rebellion has successfully mobilised activists who had relatively little previous experience of protest. This can, to some extent, be explained by a youth effect. However, if XR protesters have a similar age profile to climate change marchers (2009/10), they also have a much broader age profile than has typically been the case for environmental direct action, which in the UK at least has previously been the preserve of small networks of mainly young activists. XR has to this extent transformed the politics of direct action in the UK, and not only because many more XR activists were arrested in 2019 than in these previous waves of environmental direct action. Nonetheless, XR protesters’ socio-demographic profile looks strikingly familiar to observers of environmental and related movements. XR can justifiably be placed within a longer UK tradition which Frank Parkin, in his study of CND in the late 1960s, called ‘Middle Class Radicalism’ (1968; see also Cotgrove and Duff, 1980, on earlier environmental activism). As with CND, activists in XR are much more likely than the general population to have a university education, to identify on the left, to be members of other political organisations, and to express their political motivations in moral terms, as a responsibility to do what they can to avert a catastrophe.

Part of the appeal of XR as a vehicle for action on climate change may be because it reflects a wider mood in progressive politics. Political scientists have previously identified critical citizens to be those who ‘adhere strongly to democratic values but who find the existing structures of representative government, invented in the 18th and 19th centuries, to be wanting’ (Norris 1999: 2). As our evidence shows, XR activists are highly politically engaged while also disenchanted with conventional ways of doing politics, and have little faith in governments to make the changes required to avert a climate catastrophe.

More recently, Paolo Gerbaudo (2017) has coined the term citizenism to understand the left-progressive movements that developed across southern Europe in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008-9. These movements revealed a desire for collective political participation, occupying public spaces, and seeking new forms of participatory democracy, demanding the return of sovereignty to the people from financial and political elites. For XR, whose roots are also in this wider wave of anti-austerity social movements, this form of citizenism is visible in the campaign’s demand for citizens’ assemblies, for governments to act based on the evidence of climate breakdown, and to ‘(re)locate relations of power in the physical space of the everyday’ (Hayes 2017: 32). For the ‘ordinary’ respondents to our surveys, citizenism is visible in the sense of moral obligation to act that drives their public participation and social agency.

The challenge for the new climate activists of XR, as for all movements based on citizenism, is how to sustain action beyond asserting their demands, and how to build effective alliances that can reach beyond their core social base. Until the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change mobilisations looked set to be central to the political and media agenda prior to the planned COP26 in Glasgow in November 2020 (now delayed until at least November 2021). Dependent on what kind of politics develops post COVID-19, if XR makes the right strategic decisions, it has the opportunity to continue to shape climate politics domestically and, potentially, internationally.

Footnotes

[i] Erratum: in a previous version of this report, we mistakenly claimed that 6 million people participated in the March 15 2019. The correct figure is 1.6 million. We wish to thank Eliza Hyde Smith, an undergraduate student at University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada for noticing this typographical error.

[ii] Extinction Rebellion, ‘We set our mission on what is necessary’, Our Principles and Values, last accessed 29 May 2020: https://rebellion.earth/the-truth/about-us/

[iii] Extinction Rebellion powerpoint presentation, October Rebellion Action Design Version 1, 25 September 2019

[iv] For example, Cornwall’s ordinary rebels: How Extinction Rebellion turned us into arrestables, Cornwall Live, 28 April 2019: https://www.cornwalllive.com/news/cornwall-news/gallery/cornwalls-ordinary-rebels-how-extinction-2808121; ‘Time is running out’: XR activists on why they risked arrest, The Guardian, 30 September 2019: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/sep/30/time-is-running-out-xr-activists-on-why-they-risked-arrest; The rebels, The Tortoise, 1 October 2019: https://torto.se/2n7rr0B

[v] XR has no formal members: those who accept its principles and take action to support its demands are effectively part of the movement. To the extent that there is a ‘membership’, it consists of participants in its meetings and public protests:

[vi] We did not survey children and young people under 18.

[vii] Public Order Act 1986, s14. Section 14 concerns public assemblies; arrests covered failure to disperse, obstruction of the public highway, and so on: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1986/64/section/14

[viii] Metropolitan Police Service, Total costs for the Extinction rebellion protests in April 2019, June 2019: https://www.met.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/foi-media/metropolitan-police/priorities_and_how_we_are_doing/corporate/met-operations—extinction-rebellion—april-2019.

[ix] This percentage feels intuitively correct: on each of the seven occasions, hearings were taking place in two courts, and we covered one court. Given that we attended on roughly one third of potential occasions, it logically follows we covered around a sixth of the possible pool of hearings.

[x] We chose not to collect occupation data in April; in previous protest surveys we had found it unusable because respondents had used variable terms and degrees of specification that were oftentimes too generic to allow us to make accurate classifications.

[xi] As indicated in the responses to a question on occupation asked in the October survey.

[xii] The total number of cases was 144, but 12 were heard in absentia.

[xiii] Freedom of Information request reference 01.FOI.19.010861, August 2019: https://www.met.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/foi-media/metropolitan-police/disclosure_2019/august_2019/information-rights-unit—ethnicity-of-individuals-charged-in-the-extinction-rebellion-protests-over-easter-2019

[xiv] See Extinction Rebellion Newsletter, UK Newsletter #6: Vote for the Planet!, 9 December 2019: https://rebellion.earth/2019/12/09/uk-newsletter-6-vote-for-the-planet/

[xv] Boris Johnson calls Extinction Rebellion protesters ‘uncooperative crusties’, Metro, 8 October 2019: https://metro.co.uk/2019/10/08/boris-johnson-calls-extinction-rebellion-protesters-uncooperative-crusties-10879623/

[xvi] See for example Iain Dale’s LBC interview with Rupert Read, Radio host laughs as climate activist admits he just took a taxi—’HYPOCRITE’, The Express, 18 April 2019: https://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/1115872/extinction-rebellion-london-protest-climate-protest-lbc-taxi-video; Donald MacLeod: What did London do to deserve Extinction Rebellion, another bunch of deluded toffs and timewasters?, The Sunday Post, 22 April 2019: https://www.sundaypost.com/fp/donald-macleod-what-did-london-do-to-deserve-extinction-rebellion-another-bunch-of-deluded-toffs-and-timewasters/; EXCLUSIVE—Revealed: ‘Rank hypocrisy’ of globetrotting Extinction Rebellion jet setter’s lifestyle after she shed ‘crocodile tears’ over climate protest that stopped son seeing his dying dad, Mail Online, 25 July 2019: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-7280851/Rank-hypocrisy-globetrotting-Extinction-Rebellion-jet-setters-lifestyle-luxury-holidays.html; Conservative MP for Monmouth David Davies’s letter to the ‘climate protest backing pop group’ The 1975, asking them if they were setting off on their world tour ‘by train or yacht’, 27 August 2019: https://twitter.com/DavidTCDavies/status/1167343239822790656?s=20

[xvii] Dominic Lawson, Deluded middle-class climate warriors can’t see the real danger of their bright idea, Mail Online, 15 April 2019: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-6922371/DOMINIC-LAWSON-Deluded-middle-class-climate-warriors-real-danger-bright-idea.html

[xviii] See Extinction Rebellion, Our Principles and Values, last accessed 29 May 2020: https://rebellion.earth/the-truth/about-us/

The full report is available for download in pdf (2.1MB). | Saunders C, Doherty B and G Hayes 2020. A New Climate Movement? Extinction Rebellion’s Activists in Profile. CUSP Working Paper No 25. Guildford: Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following researchers for their contribution to this research. Lily McAuley and Marc Hudson for research assistance; for help with surveying Clare Cummings, Carys Hughes, Alice Swift, Emily Westwell (April); Joost de Moor, Emily Marsay, Joyce Liang, Molly Bond, Isabella Sanders and Anya Barbieri (October); and for court observation, Steven Cammiss and John Baptiste Oduor. We are also grateful to Zoe Blackler of XR Press Office for her comments on the draft manuscript of this report, and to all the XR activists who responded to our survey. All views are those of the three authors. The financial support of the Economic and Social Research Council for the Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity (ESRC grant no: ES/M010163/1) is gratefully acknowledged.