The Commonplaces of Environmental Scepticism

Richard Douglas

CUSP Working Paper Series | No 17

Summary

In the nearly five decades since its publication, the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth report has failed to secure a decisive victory in political debate, despite being based on the seemingly common sensical proposition that infinite growth is impossible on a finite planet. To investigate why the ‘limits to growth’ has not led to decisive political action, this paper examines the thought of its most explicit critics in debate, defined here as ‘environmental sceptics’. While many studies of this discourse have examined the economic interests and political motivations of its speakers, this paper (while also drawing on the theories of Dryzek, and of Boltanski) employs Wayne Booth’s ‘Listening Rhetoric’, used to understand opposing discourses on their own terms. In this context, this means performing an attentive reading of the rhetorical commonplaces—the taken-for-granted truths and values a speaker would expect to be shared with their audience—drawn on by environmentally sceptic speakers, in order to ‘read off’ the positive values and vision of the world that they are keen to defend.

The paper performs a close reading of a range of texts, which, while produced over four decades up to the present day, embody a coherent corpus of thought. It finds in the commonplaces on display a defence of individualism, practical reason, humanism, material power, an unbounded sense of destiny, and the fundamental benevolence of our world. In this sense, it argues that the discourse of environmental scepticism could be viewed as defending an overarching world-view of modernity against an attack on its foundations implied by the ‘limits to growth’ thesis. In the extent to which this is true, it suggests that the challenge posed by the ‘limits to growth’ runs beyond the level of ordinary political debate, pointing to a crisis of philosophical anthropology: who are we, and how should we live, if we now believe that progress will not continue forever?

Introduction

It is nearly half a century since the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth report (Meadows et al. 1972) was published. The thesis at its core—that infinite growth is impossible on a finite planet—is a seemingly common sensical proposition. Moreover, the evidence gathered by environmental scientists increasingly suggests an urgent case for curtailing our exploitation of nature: according to a range of environmental scientists, four of nine vital planetary boundaries have already been pushed beyond ‘safe’ limits (Steffen et al. 2015). Despite this, the environmentalist case has failed to secure a decisive victory in political debate internationally. Indeed, far from moving beyond debate to truly decisive political action (e.g. towards radical decarbonisation of economies), in many countries even the debate on environmental policies has faded in political salience in recent years (Scruggs and Benegal 2012).

To help to understand why the ‘limits to growth debate’ has still not yet led to the kind of rapid social transformation the Club of Rome originally hoped for, it makes sense to examine the rhetoric of environmentalism’s direct opponents, the ‘environmental sceptics’. In criticism, the speakers of this discourse are sometimes referred to as the ‘Green Backlash’ (Rowell 1996), the ‘brownlash’ (Ehrlich and Ehrlich 1996), ‘anti-environmentalism’ (Brick 1995), the ‘environmental opposition’ (Switzer 1997), or perhaps most popularly, ‘climate denialists’. The more neutral term ‘environmental sceptic’ (deriving from Bjørn Lomborg’s The Skeptical Environmentalist (2001)) is preferred here, as part of an attempt to understand this movement on its own terms. This is not to endorse this movement’s arguments; on the contrary this paper is written from an environmentalist perspective which upholds the ‘limits thesis’. Nor is it to endorse this movement’s claim to the title of ‘scepticism’, since, as we shall see, this scepticism is typically applied in a highly limited and partial fashion. It is, however, a contention of this paper that the sentiments of environmental scepticism are representative, though in a peculiarly explicit form, of a general disquiet about the negative implications of the ‘limits thesis’ (which may be shared widely, and even felt on some level by those supportive of environmentalist propositions). It is suggested here, then, that we may learn something about a wider social reluctance to accept the ‘limits thesis’ by focusing on the arguments of its most partisan opponents; and that we will best understand the resonance of these arguments by giving them an attentive hearing, bracketing out any logical or empirical criticism which might otherwise obstruct one’s ability to pay attention to the ideas they are defending.

The approach outlined here draws support, in particular, from three sources: John Dryzek’s reading of the limits to growth debate, Luc Boltanski’s work on regimes of moral justification, and Wayne Booth’s promotion of ‘Listening Rhetoric’. As Dryzek portrays it, in the early 1970s environmentalism opened up the social questioning of a dominant, but for this reason largely unconsciously-supported, ‘Promethean discourse’ which celebrated ‘capitalism and the Industrial Revolution, with its unbounded faith in the ability of humans to manipulate the world in ever more effective fashion’. The literature of environmental scepticism (though Dryzek does not use this term) is thus a product of this discourse’s being ‘pressured to articulate its key tenets for the first time’ (2013, p. 64). If we understand environmental scepticism in this way, the disquiet registered by its rhetors will certainly encompass personal and class fears of direct economic losses as a result of environmental policies; but also, I would suggest, we may detect here a sense of existential angst, felt more popularly at the idea of imposing limits to the forward momentum of human progress.

If Dryzek lends an interpretation specifically of environmental debate, Boltanski (writing in collaboration, in the works drawn on here, with Laurent Thévenot (2006) and Eve Chiapello (1999)), offers a synoptical approach to analysing political debates in general. His focus is on the necessity for different ideologies (defined as a ‘set of shared beliefs, inscribed in institutions, bound up with actions, and hence anchored in reality’ (1999, p. 3)) to justify themselves in the presence of rival systems, or simply defend themselves against moral condemnation of a specific situation they allow. In particular, he focuses on the need for the ‘dominant ideology’ of capitalism to justify itself against the perception of working life as a matter of being subordinated within ‘an interminable, insatiable process’ of economic production and consumption (1999, p. 7). Crucially, he writes against the practice, characterising much critical social science, of treating justificatory arguments for capitalism simply as a veil for the material interests of those who feel their elevated social position to be threatened. On the contrary, Boltanski argues, the justifications for an ideology point to a certain set of values which need to be shared by both the socially ‘strong’ and ‘weak’, in order for them to understand and functionally accept their roles within this order (1999, pp. 10–11).

A third conceptual influence is the work of those within the field of rhetoric who view rhetorical criticism as providing a practical aid to improving the quality of subsequent debate. Finlayson’s conception of ‘rhetorical political analysis’ is a case in point, this being done ‘not so as to expose or criticise [the elements of political speech…] but in order to contribute to their better understanding and more positive valuation, to ensure not less argumentation but more and better’ (2007, p. 557). Another inspiration is Kenneth Burke, whose interest in rhetoric was, in Herrick’s words, ‘in large measure an interest in finding symbolic means of bringing people back together’, his concept of ‘identification’ being conceived of as ‘the antidote or necessary remedy for our alienation from one another’ (2005, p. 223). Most pertinently, the concept drawn on here is Wayne Booth’s ‘Listening Rhetoric’.[i] Booth begins from the awareness that all too frequently the opposing sides in a debate never properly listen to each other: ‘Fanatical non-listeners thus waste book after book, article after article, attacking selected extremes, while dogmatically preaching to some version of their own side’ (2004, p. 153). Debate is hereby deformed, turned into performed hostility to the other side (like so many hakas, we might say). Booth says that what the world needs is a reduction in rhetorical warfare, ‘ways of probing beneath pointless disputes: methods of discovering shared ground beneath surface water’ (2004, p. 149).

This paper seeks to listen to the arguments of environmental sceptics in just such a Boothian manner. It suggests that it is necessary to engage in the justificatory arguments present in this discourse because this ought to be the key to understanding the popular receptiveness to them on the part of a significant proportion of society. To put it another way, for those who believe in the necessity of an urgent decarbonisation of society, it will be essential not only to focus on the role of politicians such as Donald Trump, but also on that of the public at large—not least, the 63 million who voted for him in 2016, despite his well-known view that ‘climate change [is] bullshit’ (Matthews 2017).[ii]

The analysis of rhetorical commonplaces

If the subject matter of this paper is the argumentation used by environmental sceptics to defend a ‘Promethean discourse’ of indefinite growth, and the spirit of this paper is one of seeking to listen attentively to what could make these arguments resonant, the method in this analysis is that of rhetorical criticism. Here, I am seeking to use rhetorical criticism to ‘read off’ this discourse’s esteemed values—its vision of the good—from the ‘commonplaces’ of rhetorical argument it disposes. In this approach, this paper is again following Boltanski, who describes his method of analysis as being ‘linked, in a way, with the tradition of studying “topics” or commonplace arguments, a tradition included within the instruction in rhetoric that made up the core of the classical humanities’ (2006, p. 67).

What are commonplaces? Finlayson tells us (2007, p. 557), ‘They rely on everyday common-sense values of what is just or unjust, honourable or dishonourable, common maxims, generally approved of principles […] and commonly accepted ways of arguing.’ In studying a rhetor’s use of commonplaces, then, the critic can learn a great deal about the audience for whom such material is arranged. As Billig notes (1993, p. 126):

The important point, stressed by the textbooks of rhetoric, was that speakers might have to invent the particular arguments to be used on the rhetorical occasion, but they did not invent the basic materials from which these speeches were constructed. Thus the individual speaker does not invent the values (perhaps of heroism or of obedience to the law) to which an appeal is to be made. Instead the speaker draws upon the value-laden vocabularies which are shared with the audience. […] In so doing, the speaker appeals to, and speaks within, the sensus communis, or the sense which is commonly shared.

If commonplaces depend on already-held beliefs, it seems to follow, then a study of rhetoric should enable us to ‘read off’ the beliefs they connect to. Indeed, as Herrick writes (2005, p. 10), the study of rhetorical discourse can enable us to perceive something about the motives, values, and beliefs of both rhetor and—if receptive—the audience. Hart tells us (1997, p. 61) ‘the study of rhetoric is the study of first premises in use’, which we might understand as signifying the mobilisation, in argument, of people’s basic beliefs about the world. Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca (1969, p. 65) stress the centrality of ‘starting points’ in any rhetorical argument, the shared intellectual ground on which rhetor and audience meet (and from which they may journey together). For Booth (2004, p. 8), rhetoric is ‘the art of probing what we believe we ought to believe, rather than proving what is true according to abstract methods’—which we could read as describing rhetoric as being all about the advancement of propositions in accordance with values. Boltanski refers to Cicero’s ‘abundant use of the metaphor of “commonplaces” from which an orator can “dig out” his proofs and draw his arguments’, quoting him to the effect that: ‘It is easy to find things that are hidden if the hiding place is pointed out and marked; similarly if we wish to track down some argument we ought to know the places or topics: for that is the name given by Aristotle to the “regions,” as it were, from which arguments are drawn’ (2006, pp. 68–9). In the case in hand, we could understand this to mean that it is not hard to trace the roots of environmentally sceptic arguments: they are in plain sight, visible in the assumptions they display and mobilise as to what is good and right.

In short, in attending to the commonplaces used by environmental sceptics, we may hope to discover an outline of their key philosophical beliefs. Finlayson provides support for this proposed method in writing that ‘analysis of ideologies […] suggests that different sets of commonplace are drawn on in liberal or conservative arguments’ (2007, p. 557). In this case, the aim will be to examine the appeals made in these texts inductively, and thereby build up a picture of the overarching beliefs they are defending.

The commonplaces of environmental scepticism

The following analysis engages with a number of texts selected for their prominence within the development of environmental sceptic arguments, or for the representative nature of the particular points they make. Most are connected via networks of climate sceptic think-tanks, such as the Global Warming Policy Foundation in the UK (founded by Lord Lawson, a Chancellor of the Exchequer under Margaret Thatcher), the Institute of Public Affairs in Australia, and the Reason Foundation in the US. Following Boltanski (who suggests that ‘As work based on other corpuses has shown […], the choice of source texts is not of great significance’) I am not claiming any significance for this precise selection of texts. The important fact is they are ‘defined with reference to a common polity [and thus] contain roughly the same terms and refer to the same objects’ (2006, p. 153). One factor that does lie behind their selection is timespan: in selecting texts that span four decades up to the present, I seek to show both that there is a persisting coherence to this discourse, and that it is currently active.

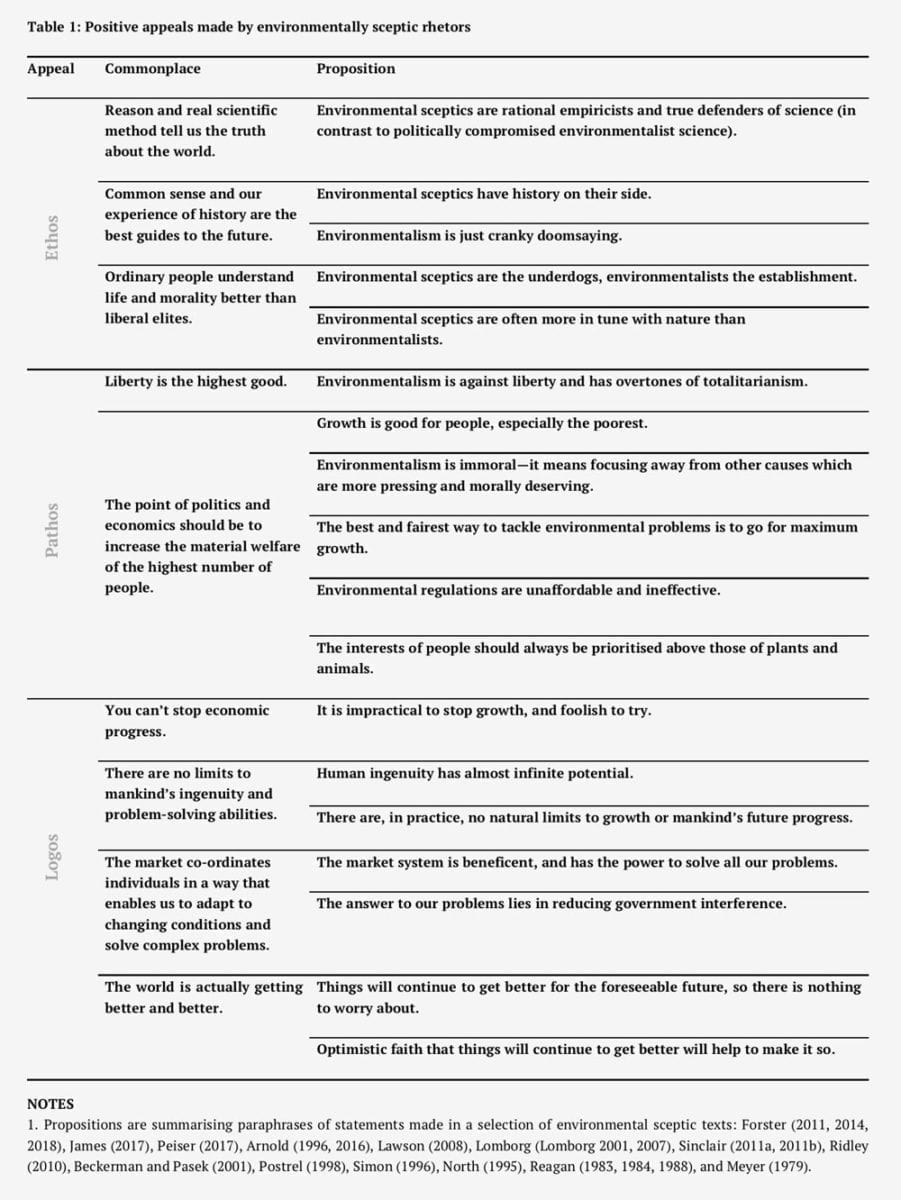

Table 1 presents the results of this analysis in brief, beginning with paraphrases of the main propositions made, directly or implicitly, in these texts. These propositions are organised according to a smaller number of more overarching commonplaces (statements of virtue or quality as would be commonly-accepted, it is suggested, within this literature’s target audience) that they appear to be linked to. These commonplaces are then organised according to which of the three classic rhetorical appeals—ethos (establishing the rhetor’s character and personal authority), pathos (the emotional implications of a case), or logos (the rational support for an argument)—they principally belong to. In classical rhetoric, ethos, pathos, and logos were thought of as distinct forms of appeal that a rhetor could utilise in order to win an audience over. Here, I am merely using these terms as a convenient tool for grouping together forms of argument by underlying themes. I am not suggesting, for example, that if a certain environmental sceptic deploys an argument which advertises their own personal integrity (i.e., appealing to ethos) that this is the only form of appeal they will make; the same rhetor might well make full use of appeals to pathos and logos as well. The main point of brigading commonplaces in this way is, by drawing attention to the different registers in which these rhetors are seeking to be persuasive, to focus on this essential drive for persuasiveness common to them all.

Ethos

Beginning with the appeal to ethos, the first thing we may note is that while environmental sceptics argue continually against the findings of science as used by environmentalists, they are not seeking to argue against science itself. Rather, they seek to appropriate the status of scientific authority for themselves, stressing they are in tune with the genuine spirit of science—unlike much of the mainstream version, which to them has become compromised by environmentalist ideology, dependence on research grants, and the glamour of a fashionable cause.

Commonplace: Reason and real scientific method tell us the truth about the world

One of the major themes in this literature is an appeal to scepticism, invoked as a positive value which protects us against falling into error. Conceived in this manner, as the protector of certainty, scepticism implies some method which can actualise its promise and deliver us answers whose truth we do not need to doubt. For Bjørn Lomborg, author of The Skeptical Environmentalist, this method is statistical analysis: ‘I always tell my students how statistics is one of science’s best ways to check whether our venerable social beliefs stand up to scrutiny or turn out to be myths’ (2001, p. xix). By focusing on hard data we will uncover an underlying level of reality, beyond that of mere appearance and popular opinion: we will get down to ‘the fundamentals’ (2001, p. 3). This process must be carried out in the right spirit: that is, with a reverence for truth. Loyalty to the truth, even if it contradicts what we wish to find, is what separates the environmental sceptic from the environmental campaigner: it is ‘crucial that we cite figures and trends which are true. This demand may seem glaringly obvious, but the public environment debate has unfortunately been characterized by an unpleasant tendency towards rather rash treatment of the truth’ (2001, p. 12). In this way, debate between environmental sceptics and environmentalist campaigners necessarily amounts to a conflict of ‘Reality versus myths’ (2001, p. 13). Environmentalists’ ‘rhetorically pleasing’ (2001, p. 30) arguments are distorted by the emotion of ‘worrying’, resulting in ‘the Litany’, a list of environmental tribulations which add up to the received opinion that environmental exploitation is getting ever worse. This is a dangerous development, because deceptive: ‘If we do not make considered, rational decisions but base our resolution on the Litany, that typical feeling that the world is in decline, we will make poor and counterproductive choices’ (2001, p. 350).

Within this discourse science is revered—but a sharp contrast drawn with a bogus version that has been warped by ideology and special interests. The environmental sceptic Freeman Dyson is celebrated as one who has ‘served science’ and been one of our ‘true figures of authority’; but increasingly, we are told, scientists in that mould are an embattled minority. Those ‘few hold-outs who go on fighting to defend the objective nature of truth’ are ‘in short supply’: given they ‘care more about science than about the media’, they ‘tend not to have much influence when they get to speak.’ In the opposing corner we find ‘a bunch of grant-dependent climate scientists’ who ‘get famous [by] serving themselves’ (James 2017, pp. 5, 8–9). At its mildest, the dependence of climate scientists on expensive computer modelling can lead to a culture of ‘Groupthink’, not only because ‘if you started expressing a sceptical view you wouldn’t get grants for the equipment’, but because ‘the untestability of [projections of the future…] means that you tend to get carried along with the crowd, because you can’t do the experiment to prove it’s not true’ (Forster 2018). At its worst, as Clive James finds, the climate science establishment is seen as having parallels with the politically-approved version of science under totalitarian regimes, as represented by the figure of Trofim Lysenko. While such figures ‘might have started out as scientists of a kind, [they] have found their true purpose in life as ideologists’. This perversion of science has so damaged the ‘cause of rational critical enquiry’ that ‘Some of the universities deserve to be closed down’ (James 2017, pp. 10, 8).

Another of the values to which the sceptics make great appeal is that of reason. Environmentalism is by contrast presented as illogical and fantastical, a piece of far-fetched fiction. Global warming is thus a ‘religion’ which ‘resembles a Da Vinci Code of environmentalism. It is a great story, and a phenomenal best-seller. It contains a grain of truth—and a mountain of nonsense.’ In the extent to which this story has been taken literally, we ‘have entered a new age of unreason’. This is the real danger we face today: it is from this ‘profoundly disquieting’ state of collective delusion, ‘that we really do need to save the planet’ (Lawson 2008, p. 106).

Commonplace: Common sense and our experience of history are the best guides to the future

Empiricism, and the practical experience of ordinary folks, is admired in this literature, while an excessive use of theory by intellectuals and professional experts is deprecated. Environmental sceptics place great weight on the common historical experience of material progress, with no one communicating this argument more eloquently than Ronald Reagan. In one speech as president (Reagan 1983), he began by recalling the Great Depression—‘If ever there was a time to talk about limits to growth, it was then’—before commenting: ‘But here we are half a century later, and the American people enjoy a standard of living unknown back in the thirties or even before the thirties’. Meditating on technological progress during this time, he added:

And think of the things that we take for granted today that didn’t even exist before—television, computers, space flights. […] I’ve already lived some two decades longer than my life expectancy when I was born. That’s a source of annoyance to a number of people. [Laughter.] But life on Earth is not worse; it is better than it was when I was your age. And life in the United States is better than ever.

This recollection of progress is clearly based on a material reality that would have resonated with masses of people—certainly in the 1980s, and certainly in the West. Within the discourse of environmental scepticism, however, it has long been transmuted into an article of common sense that it must continue forever, that growth is the way of the world. After all, ‘when things are improving we know we are on the right track’; and in case of any doubt that such progress could continue in the face of climate change and other environmental dangers, ‘we have to constantly keep focus on the fact that humanity has dealt with and overcome problems all through history’ (Lomborg 2001, pp. 5, 290). This seemingly hard-headed reference to historical experience is often contrasted with the speculative quality of environmentalists’ warnings about what may happen in the future. Environmentalists are ridiculed as ‘doomsayers’, their warnings portrayed as being spun out of their imaginations and conditioned by a psychological bent towards pessimism: ‘Professor Ehrlich […] predicted mass death by extreme cold. Lately he predicts mass death by extreme heat. But he has always predicted mass death by extreme something, and he is always Professor Ehrlich’ (James 2017, p. 1).

In fact, historical examples of millenarian movements that awaited the imminent end of the world, as well as the more general phenomenon of periodic worries over cultural decline, is itself used to give an empirical basis to the argument that environmentalist warnings are necessarily exaggerated. Environmentalism is just the latest manifestation of an ancient theme of irrational angst: ‘Throughout the ages, something deep in man’s psyche has made him receptive to apocalyptic warnings: “the end of the world is nigh” ’ (Lawson 2008, p. 102). But ‘all the apocalyptic prophecies of this nature will turn out to be falsified in the same way that all such prophecies have been falsified in the past’ (Beckerman and Pasek 2001, pp. 194–5). This expectation that prophecies of doom will necessarily be false can further be used to support the argument that predictions of an environmentally benevolent future will necessarily be true. Lomborg begins his Skeptical Environmentalist with a quotation from Julian Simon, which predicts: ‘The material conditions of life will continue to get better for most people, in most countries, most of the time, indefinitely. […] I also speculate, however, that many people will continue to think and say that the conditions of life are getting worse’ (2001, p. vii). In the way that these predictions are paired, the very existence of environmentalist concerns is framed as though confirming the proposition they are baseless.

Commonplace: Ordinary people understand life and morality better than liberal elites

Another dimension to this celebration of common sense is an identification of environmental scepticism with the spirit of democracy. There is a strong aversion in these arguments to the idea of accepting things on authority, or worse, being told what to believe. Instead, there is a strong attachment to the idea that one can determine the truth for oneself through one’s private reasoning and observation: ‘The key idea is that we ought not to let the environmental organizations, business lobbyists or the media be alone in presenting truths and priorities. Rather, we should strive for a careful democratic check on the environmental debate, by knowing the real state of the world’ (Lomborg 2001, p. xx). In this spirit, the Director of the Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF), sees his mission as opening up the work of climate scientists to democratic scrutiny: ‘I certainly don’t believe in science by authority, that’s for sure. I believe in science by solid arguments and factual arguments, and there are […] extremely brilliant science bloggers who have discovered flaws in papers […] and why shouldn’t they be heard?’ (Peiser 2017). For another member of the GWPF, the one-sided nature of public information on climate science means that ‘we always do have to take a slightly different view [to mainstream science] to an extent’, but that this is ‘a good thing to do in itself’ because it is only by redressing the balance and testing the mainstream view that one can ‘engender a healthy critical debate’ (Forster 2018).

Another common theme, extending from this identification with democracy, is the populist argument that environmentalism is a defining property of a cosmopolitan elite. In this case it is not the material inequality such an elite embodies that is objected to, so much as their superficiality and intolerance of dissent. At best, environmentalism is a performance for ‘people [who] feel better when they drive a hybrid car or ride a bicycle to work, and like to parade their virtue in this way’ (Lawson 2008, p. 103). At worst, this solidifies into the ethos of a class which, secure in the opinion of its own virtue, is blind to its hypocrisy. Clive James (2017, p. 3) attacks Julia Gillard for buying a house on the beach, having been a ‘prophet of the rising ocean’; but his real ire is directed at ‘the consensus of silence from the wits and thespians’ who refuse to satirise such a ready target, due to climate change’s being an article of faith among their kind. In this context, environmental sceptics celebrate themselves as being, not just correct, but courageous in striking a blow for those who feel oppressed by the cultural disapproval of this liberal elite. The obvious delight one writer takes in referring to his optimistic views about the environment as ‘great sins against conventional wisdom’ (Ridley 2010, p. 353) conveys the clear message that those who enforce such convention are far from wise, and their moralised condemnation of dissent illegitimate. In a stronger formulation, environmentalism is pictured as an active attempt by liberal elites to deceive society at large, as when ‘manmade global warming’ is described as ‘the greatest hoax ever perpetrated on the American people’ on the floor of the US Senate (Inhofe 2003).

A related proposition on this populist theme is that, far from being uncaring towards nature, environmental sceptics—and many ordinary people, especially those who live in the countryside—are often more in tune with nature than environmentalists. Environmentalists are often depicted as city-dwellers, whose concerns for nature are literally distant from reality, a matter of abstract ideology rather than intimate knowledge. As a result, their ideas can make matters worse, such as when, it is argued, their desire to conserve forests in a pristine state actually leaves them more combustible (‘Extreme environmentalists […] talk about habitat and yet they are willing to burn it up’ (Canon 2018)).

By contrast, sceptics are keen to stress their own credentials as intimates of nature, ‘stewarding and nurturing the bountiful earth as it stewards and nurtures them’ (Arnold 1996, p. 23). One set of claims here concerns the efficient use of natural resources, with some sceptics happy to endorse environmental technologies on the practical (and even moral) grounds of an aversion to waste (‘part of the reason we have a heat pump is because it’s a very efficient use of energy, you produce three times the amount of heat for your unit of electricity’). In this vein they may indeed talk of themselves as being ‘very committed to the good of the planet’ (Forster 2018). Another claim is to an aesthetic appreciation of the natural world (‘I’ll match my birdwatching time with just about any environmentalist, and I’ll bet that I’ve seen more birds this spring than most of your environmental friends’) (Simon 1996, p. xxxiv). In most cases, the relationship with nature they espouse is, while caring, one in which human interests are paramount (‘I don’t like to kill even spiders and cockroaches […] But if it’s them versus me, I have no compunction about killing them even if it is with regret’ (Simon 1996, p. xxxiv)). The human-centredness of this relationship is such that it tends to be unsentimental about areas perceived as wilderness, even to the extent of arguing against saving (much of) the Amazon rainforest—after all, ‘very few people have found much of a use for it as it stands’ (North 1995, p. 234). In such cases, it is not that environmental sceptics are, as it were, against the rainforest; it is just that they don’t see why it should not be exploited. What they are for is nature as part of social life:

It turns out most people like other sorts of forest much better [than the Amazon]. Parents like open forest where you can see where the kids are playing. You also want signs that tell you what you’re seeing […] It’s a very different kind of forest that most people actually want. You need a parking lot close by, that kind of stuff. (Lomborg, in Whittell 2005)

Pathos

In their appeal to ‘ethos’, then, environmental sceptics present themselves as the defenders of a democratic rationality and of a practical relationship with nature, against the attacks coming from a delusional group of elitist hypocrites. It is in their use of ‘pathos’ that they underline their case that this matters, that there is something vitally important at stake in this debate. Here we may note a twin attachment to individualism and utilitarianism. This is a highly anthropocentric view of existence: the human individual is the most important thing in the world. The highest good therefore inheres in maximising individual freedom and material wellbeing. This gives opposing environmentalism a moral character.

Commonplace: Liberty is the highest good

A common theme in this literature is to criticise environmentalism as intrinsically authoritarian, and to liken it to totalitarian movements of the twentieth century. Environmentalism is repeatedly presented as a decoy: the ‘alleged horrors of global warming’ are merely a ‘licence to intrude, to interfere and to regulate’, pursued by ‘those who wish to take power to order us how to run our lives’ (Lawson 2008, p. 101). Environmentalism may ‘All sound good in the abstract. But scratch the surface and you will as likely as not discover anti-capitalism […] and intrusions upon the sovereignty and democracy of nations’ (Thatcher, in Charter 2003). For some, ‘the climate change fad itself is an offshoot of this lingering revolutionary animus against liberal democracy’ (James 2017, p. 10).

Behind environmentalism, these writers argue, we can see the spectres of communism and fascism. ‘With the collapse of Marxism, […] those who dislike capitalism […] have been obliged to find a new creed. […] For many of them, green is the new red’ (Lawson 2008, p. 101). Indeed, many environmentalists ‘used to be communists or socialists, but history has been unkind to them, and now all they can do is complain about pollution’ (Friedman 1995, pp. 11–12): ‘The Red Star is burned out, but the Green Star is rising’ (Rowell 1996, p. 244). Such allusions are not confined to Soviet communism but extended to fascism, too—Greenpeace being likened to Goebbels (Lindzen, in Rowell 1996, p. 244), greens to ‘Hitler-loving imperialists’ (Durkin, in Pallister et al. 2000), and the US Environmental Protection Agency to a ‘gestapo bureaucracy’ (Inhofe, in Mooney 2005, pp. 78–9).

The pathos of this argument is underlined in those cases which direct our attention to the tyrannical nature of the regimes alluded to. ‘Like Marxism,’ environmentalism may appear virtuous, but it is ‘the green road to serfdom’ (Postrel 1990). We should therefore be ‘suspicious of over-idealistic positions’ such as many environmentalists take, remembering that ‘the history of the twentieth century […], in its worst communist and fascist forms, it is a sort of history of idealism causing havoc’ (Forster 2018). Beckerman and Pasek, in this context, pointedly quote Isaiah Berlin as recalling the literal ‘sacrifice’ such regimes made ‘of living human beings on the altars of abstractions – nation, Church, party, class, progress, the forces of history […]’ (2001, pp. 111–12).

Another bridge to this historical tradition of anti-totalitarian writings is visible in the references to environmentalism’s religious character. Nigel Lawson, for example, writes:

I suspect that it is no accident that it is in Europe that eco-fundamentalism in general and global warming absolutism in particular, has found its most fertile soil; for it is Europe that has become the most secular society in the world, where the traditional religions have the weakest hold. Yet people still feel the need for the comfort and higher values that religion can provide, and it is the quasi-religion of green alarmism […] which has filled the vacuum, with reasoned questioning of its mantras regarded as little short of sacrilege. (2008, p. 102)

Lawson can be seen here working with the idea of totalitarian movements functioning as a form of ‘political religion’, as advanced by the likes of Raymond Aron in the 1930s.[i] The operative quality here is ‘fundamentalism’: this is a view of religion in which, disconnected from its traditional sphere, it re-emerges as a particularly irrational force, mobilising its followers around impossible goals of worldly transformation. This view of radical political movements understands that ‘religious passions, you know, once the genie’s out of the bottle, they don’t go back in the bottle. They get displaced into other activities’ (Forster 2018). In the case of environmentalism, this can take the form of a ‘guilt-driven, quasi-religious Western fervour to save the planet’ (Forster 2014, p. iv).

Commonplace: The point of politics and economics should be to increase the material welfare of the highest number of people

One element of the environmental sceptics’ presentation of pathos is thus a warning against state terror, and a complementary defence of an ideal of limited government which protects individual liberty. The other element makes the case that environmentalism is harmful to the material wellbeing of society, most of all to those most in need.

This is often presented as a simple matter of morality: ‘It is precisely because there is still far more suffering and scarcity in the world than I or anybody else with a heart would wish that [… we have] reason for pressing on urgently with economic progress, innovation and change, the only known way of bringing the benefits of a rising living standard to many more people’ (Ridley 2010, p. 353). The logic of this argument is equally simple: ‘In the developing world, the major cause of ill health and the deaths it brings, is poverty. Faster economic growth means less poverty’. By calling for the imposition of limits to growth, ‘the would-be saviours of the planet are, in practice, the enemies of poverty reduction’ (Lawson 2008, pp. 33, 105–6).

In addition to an overall opposition to economic growth, specific policies pushed by environmentalists are also adjudged to bear down on poorer communities in particular. Examples cited include subsidies for renewable energy generation which are paid for out of increases to household fuel bills, meaning, for instance, that ‘the subsidies for Scottish landowners with lots of windfarms are being paid by the poor of Glasgow’ (Forster 2018). Another example given is that of the Grenfell Tower disaster, in which a fire in a London social housing high-rise block in June 2017 led to the deaths of 72 people:

Because what happened with Grenfell Tower was that you put this insulating cladding on to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. That’s the reason for it, it’s environmental to make these things better insulated. And the cheapest, most effective insulation happened to be inflammable, and nobody noticed. And so they give preference to what is in effect a climate policy, a policy on carbon dioxide, [….] over safety. (Forster 2018)

Bjørn Lomborg presents a range of arguments on this general theme. He starts with the premise that ‘The only scarce good is money with which to solve problems’. This means that, ‘We are forced constantly to prioritize our resources, and there will always be good projects we have to reject’ (2001, p. 9). More money spent on the environment necessarily means less spent on ‘health, education, infrastructure and defense’ (2001, p. 31). This is precisely what makes environmentalism harmful: ‘The constant repetition of the Litany and the often heard environmental exaggerations has serious consequences. It makes us scared and it makes us more likely to spend our resources and attention solving phantom problems while ignoring real and pressing (possibly non-environmental) issues’ (2001, p. 5).

From this point, we could identify two related arguments. First, in seeking to prioritise among various public spending options, one should choose where to prioritise our resources by ‘Counting [human] lives lost from different problems.’ While this ‘does not mean that plants and animals do not also have rights’, it does mean ‘that the needs and desires of humankind represent the crux of our assessment of the state of the world’ (2001, p. xi). Second, economic growth is understood as smoothly translating into an increase in human power, which will necessarily protect human lives, even when faced by increasing environmental risks:

If we contemplate a more environmentally oriented future, in which sea-level rises would be lower, our instincts would be to expect fewer people flooded. However, such a future would also be a less rich one—the IPCC expects the average person in the standard future to make $72,700 in the 2080s, whereas a person in a more environmentally oriented (but less growth-oriented) world would make only $50,600. Despite one-third less sea-level rise, the environmental world will likely see more people flooded, simply because it will be poorer and therefore less able to defend itself against rising waters (2007, p. 69).

On a similar theme, Lomborg writes: ‘It is often assumed that global warming will put human health under greater pressure. [… But] a much richer world will be far more able to afford most people access to air-conditioning’ (2001, p. 291). Since many proposed environmental policies would slow down economic growth and thereby make people relatively poorer, he is able to conclude that environmentalism is in general associated with greater human suffering. Thus, for example, ‘scrapping pesticides would actually result in more cases of cancer because fruits and vegetables help to prevent cancer, and without pesticides fruits and vegetables would get more expensive, so that people would eat less of them’ (2001, p. 10). More pointedly, given the number of people in the world who currently die from cold, he attacks carbon mitigation policies precisely because they would be effective in slowing down global warming: ‘as warming will indeed prevent even more cold deaths, we have to ask why we are thinking about an expensive policy that will actually leave more people dead’ (2007, p. 114). The overall conclusion to be drawn from this line of argument is that ‘only when we get sufficiently rich can we afford the relative luxury of caring about the environment’ (2001, p. 33).

The private pursuit of economic growth, in summary, is presented in this literature as the cornerstone of both liberty and welfare, and moreover the source of such material power as necessary to overawe any of the problems suggested by environmentalists anyway. As Matthew Sinclair puts it (2011b): ‘The best way to ensure that Britain can cope with climate change is to bet on growth, and build a country rich and free enough to survive whatever the climate throws at it.’

Logos

Regarding the intellectual structure of the sceptics’ arguments against the proposals of environmentalism, what stands out is an outlook which combines determinism, optimism, and a counterpoising sense of jeopardy.

Commonplace: You can’t stop economic progress

These arguments begin from a fatalistic assertion that growth—and consumption of fossil fuels—is simply the way of the world: ‘Any country with fossil-fuel reserves will exploit them’. Any attempts, therefore, by richer countries to cut back on carbon emissions will just lead to lower oil prices, ‘enabling higher consumption by poorer countries’ (Forster 2011). To think that fossil fuels aren’t ‘just going to be used’ is to adopt ‘a sort of King Canute stance’ (Forster 2018). Any individual nation, such as the UK, that wishes to take the lead on cutting carbon emissions will be engaging merely in ‘costly masochism’: the ‘futility of the moral leadership conceit’ will be seen in the ‘nugatory reduction in overall global emissions that this would lead to.’ Even implementing such a policy right across the EU would be pointless: ‘energy-intensive industries and processes would progressively decline in Europe, and expand in countries like China’ (Lawson 2008, pp. 62–3).

Commonplaces: There are no limits to mankind’s ingenuity and problem-solving abilities; The market co-ordinates individuals in a way that enables us to adapt to changing conditions and solve complex problems

This fatalistic presentation of economic reality is typically, however, presented in a positive light: our fate is a benevolent one, if only we realise it. This position is based on two complementary commonplaces: that there are no limits to human ingenuity, and that the market system enables us, by harnessing this ingenuity, to adapt to changing circumstances and continually improve our lot. Ingenuity is regarded as a protean, immaterial, and hence inexhaustible source of material power—humans have ‘limitless imaginations [that] can break through natural limits’ (Arnold 1996, p. 24), meaning that, ‘It’s reasonable to expect the supply of energy to continue becoming more available and less scarce, forever’ (Simon 1996, p. 181). Market forces put this ingenuity to work—‘scarcity drives up price; that encourages the development of alternatives and of efficiencies’, turning ‘the human race [into] a collective problem-solving machine’ (Ridley 2010, p. 281). This market feedback means ‘we will never run out of any resource, or even suffer seriously from any sudden reduction in its supply’ (Beckerman and Pasek 2001, p. 101).

Environmentalist concerns are thus real, but nothing to worry about; they are merely grist to our economic mill. All we need is faith in ourselves:

At work is a general process […]: humans on average build a bit more than they destroy, and create a bit more than they use up. This process is, as the physicists say, an ‘invariancy’ applying to all metals, all fuels, all foods, and all other measures of human welfare, in almost all countries at almost all times; it can be thought of as a theory of economic history. The crucial evidence for the existence of this process is the fact that each generation leaves a bit more true wealth – the resources to create material and nonmaterial goods – than the generation began with. (Simon 1996, p. 582)

Understanding ourselves in this way, we can see that humans are good for the environment: ‘We are actually leaving the world a better place than we got it’ (Lomborg 2001, p. 351). We therefore have every cause to be ‘rational optimists’ about the future:

And the good news is that there is no inevitable end to this process. […] There is no reason we cannot solve the problems that beset us, of economic crashes, population explosions, climate change and terrorism, of poverty, AIDS, depression and obesity. It will not be easy, but it is perfectly possible, indeed probable, that in the year 2110, a century after this book is published, humanity will be much, much better off than it is today, and so will the ecology of the planet it inhabits. This book dares the human race to embrace change, to be rationally optimistic and thereby to strive for the betterment of humankind and the world it inhabits. (Ridley 2010, p. 7)

At the same time, even while presenting such an optimistic case, these writers tend to sound a note of alarm. We do face challenges and risks, and things may go wrong—if we falter, losing faith in ourselves and the possibilities of human ingenuity harnessed by the market. We will be tempted, in other words, by siren voices who test our faith—who argue that we should fix our problems before they get any worse, striving to limit the damage through state intervention.

This would be a great mistake, we are told, because it would stop the very thing—the drive for material progress that results in economic growth—that can save us: ‘The apparently obvious way to deal with resource problems—have the government control the amounts and prices of what consumers consume and suppliers supply—is inevitably counterproductive in the long run because the controls and price fixing prevent us from making the cost-efficient adjustments that eventually would more than alleviate the problem’ (Simon 1996, p. 584). That is to say: ‘The real danger comes from slowing down change’ (Ridley 2010, p. 281).

Virginia Postrel’s The Future and Its Enemies (1998) is a book-length meditation on this particular theme. She contrasts ‘dynamists’—those who believe in ‘constant creation, discovery, and competition’—with ‘stasists’—those who yearn for ‘a regulated, engineered world’ (p. xix). ‘Dynamists,’ she says, ‘believe in the future, in the capacity of human beings gradually and voluntarily, by trial and error, to improve their lives’ (p. 41). They view the future as an ‘infinite series’, ‘an open-ended progression of invention, learning, adaptation, and change’ (p. 59). They are thus: ‘The party of life, the party that fears no “abyss” in the unfolding future’ (p. 215). Stasists, meanwhile, are ‘scared of the future’ (p. xiv), and seek regulations to shape it according to a preferred vision. But in their pessimism they underestimate our ability, spontaneously and through the market, to overcome environmental challenges. Such stasists are ‘numerous’, and thus pose a real threat (p. 26); as ‘enemies of the future’ they must be resisted or, it seems, a different (worse) future will be realised.

Commonplace: The world is actually getting better and better

How do environmental sceptics foresee a way out of this danger? They often present this as a test of faith: having the right attitude is key. If we are to make progress we must reject the ‘counsels of despair’ from environmentalism, which represent ‘a kind of collapse of faith [… in t]he West’ (Reagan 1988). This will come about through rejecting the politics of ‘pessimism, fear, and limits compared to ours of hope, confidence, and growth’ (Reagan 1984). We must be bold; fundamentally we must reject something in ourselves, our doubts about the future, our attachments to the past. The ‘developing economy of the future’ will be one of great ‘opportunities, if only we have the courage to embrace them, to jettison the prejudices and small-mindedness of the past’ (Reagan 1988). In order ‘to take advantage of these staggering advances’ that are waiting for us, ‘we must […] meet the challenges of change’ (Reagan 1983). If we heed this call, then we are almost bound to prosper: ‘many solutions [to environmental problems] will occur almost of their own accord [….] if we take the optimistic view that solutions are not only feasible but probable’ (Allaby 1995, p. 181).

Having built up a sense of jeopardy, then, environmental sceptics tend to dismiss it again. While Postrel says that stasists will try to convince everyone that we are ‘running out of resources’, she is clear that this is ‘a prophecy inevitably contradicted by dynamic developments’ (p. 51). To Beckerman and Pasek economic growth will lead to an ‘inexorable improvement in the environment’ (p. 195). Matt Ridley states unequivocally: ‘So the human race will continue to expand […] The twenty-first century will be a magnificent time to be alive’ (p. 359). Benny Peiser has a categorical faith that we do not face any crucial tipping points, beyond which it would be impossible for us to prevent catastrophic climate change: ‘this argument it would be too late, I don’t buy that, I think there will always be enough time’ (Peiser 2017). Bjørn Lomborg states, without reservation, ‘We are not running out of energy or natural resources. There will be more and more food per head of population’ (2001, p. 4). About climate change, he is equally confident: ‘its total impact will not pose a devastating problem for our future’, so ‘we need to worry less about global warming in the long run’ (2001, pp. 4, 19). For example, ‘it seems likely […] virtually no one will be exposed to annual sea flooding’ (2001, p. 290). In fact, ‘Global warming will not decrease food production, it will probably not increase storminess or the frequency of hurricanes, it will not increase the impact of malaria or indeed cause more deaths’ (2001, p. 317). Lomborg’s confidence extends to the far future: ‘A thousand years ago we did not use oil, and a thousand years from now we will probably be using solar, fusion or other technologies we have not yet thought of’ (2001, p. 28). Julian Simon goes even further, expecting progress to continue for another seven million millennia and more: ‘After our sun runs out of energy, there may be nuclear fusion, or some other suns to take care of our needs. We’ve got seven billion years to discover solutions to the theoretical problems that we have only been able to cook up in the past few centuries of progress in physics’ (1996, p. 181).

Conclusion

It was suggested in this paper that in studying the arguments used by environmental sceptics we might be able to ‘read off’ the key values invoked in this discourse, and thus identify a vision of the good that it is seeking to defend. This is a moral defence, in other words; and we might perceive that it gains its emotional force, for those receptive to it, via a condemnation of the perceived moral shortcomings of its environmentalist adversaries. Are environmental sceptics sincere in these sentiments, or is such an assertion of moral superiority just a cynical ploy? How much does this matter?

Rhetorical criticism suggests one should take the use of moral justifications seriously, even if one would dismiss such claims as objectively illegitimate. In his analysis of rhetoric in historical context, Skinner (2002, pp. 149, 156) suggests that morality is at the heart of rhetoric, in that it works by framing some things as being worthy of approval and others of disapproval. Furthermore, he stresses that the extent to which a rhetor personally believes in the moral ideals he or she invokes is immaterial: the rhetorical invocation of morality, if successful, will still key into, and reshape or reinforce, the boundaries of what it is socially acceptable—at least within a certain group—to say or do.

In the context of this paper, the suggestion is that the rhetoric of environmental scepticism works by affirming the moral goodness of an ideology of growth and progress, and of those who defend it, against the moral critique of environmentalism. It also provides a clue as to how debate, from an environmentalist perspective, might be more productively conducted with environmental sceptics and those amenable to their arguments. Perhaps it might be possible to find, on a deeper or more abstract level, a set of moral principles into which the more specific values of both environmentalism and environmental scepticism could both be translated. From such a common ground of moral beliefs, perhaps it would be possible to initiate practices of Boothian Listening Rhetoric, which, for example, might allow some of those amenable to the arguments of environmental sceptics to engage more fairly with the cases made by environmentalism.

But this paper began by suggesting something more than the importance for environmentalists to engage the arguments of environmental sceptics, with the practical aim of influencing their political views—as important as this is. It also suggested that environmental sceptics in some way articulate a wider sense of unease (shared, to some extent, even by those who are opposed to environmental scepticism) at the ‘limits thesis’ and what it implies for the discourse of modernity. To return our focus to this point, surveying the preceding analysis of commonplaces we can find defences of a belief in: individualism (the power to determine the truth for oneself), practical reason (we can understand, and thus exploit, natural laws through observation and experiment), humanism (people are the most important and creative features of existence), material power (we will continue to enjoy ever-growing technological means to realise our will), an unbounded sense of destiny (mankind journeying into an endless future, on an infinite voyage of discovery), and the fundamental benevolence of our world (humanity has discovered the key to progressively improving life, a process that will continue indefinitely, so long as we do not lose faith in ourselves). We can readily recognise these ideas as tropes of modernity, the Enlightenment, and classical political economy.

Highlighting what environmental sceptics are defending helps, in turn, to reveal what environmentalism—in the sense of the implications of the ‘limits thesis’, which says there are limits to progress, and that technology cannot just save us—is attacking. In this sense, we might see environmentalism itself as undermining the foundations of an overarching world-view of modernity. Perhaps, in this light, environmental scepticism begins to make more sense; it appears to be defending—even through a dogmatic refusal to believe in scientific evidence and reasoned argument—the epoch of modernity. What this highlights is that the challenge posed by the ‘limits thesis’ runs beyond the level of ordinary political debate. The crisis it points to is at its most fundamental level one of philosophical anthropology: who are we, and how should we live, if we now believe that progress will not continue forever? What will we be living for? Ultimately, if this suggestion is correct, it will only be on this philosophical level that a truly and socially persuasive and transformative solution may be found.

Notes

[i] See also Andrew Dobson’s Listening for Democracy (2014), and Dryzek and Lo’s work on ‘bridging rhetoric’ (Dryzek and Lo 2015).

[ii] This is not to suggest that everyone who voted for Trump shared his views on climate change, or that this was the decisive reason why anyone voted for him. The point is more that his anti-environmentalist views were well known, and in this sense, that such a large number of people voted for him represents a mass (at least tacit) endorsement of the ‘acceptability’ of such views.

[iii] See Gentile (2006) for a discussion of the development of the concept of ‘political religion’ as an interpretation of totalitarian movements in the twentieth century.

The full paper is available for download in pdf (1MB). | Douglas, R 2018. The Commonplace of Environmental Scepticism. CUSP Working Paper No 17. Guildford: University of Surrey.

A blog summarising the paper can be accessed on our blog page.