Customer engagement in the circular economy: Lessons from small fashion businesses

A recent study by Patrick Elf and Andrea Werner showcases small enterprises in the UK fashion industry that implement extended circular economy practices with an aim to influence their customers’ consumptive behaviour. This blog introduces some of the details.

Blog by PATRICK ELF and ANDREA WERNER

Much has been written about the Circular Economy (CE) in recent years. Besides its enormous potential, and apart from its hype and buzzword status, CE has come under growing scrutiny because it mainly focuses on eco-efficiency product improvements, promoting the use of fewer resources per product. This is all nice and well, weren’t it for the context of an economy that relies on continuous economic growth, thus encouraging more primary production, not less—the rebound effect. As Roland Geyer puts it in his recent book (Geyer, 2022), “it is not enough just to generate a circular economy. Instead, what matters is to what extent the circular economy does away with our current linear economy’”[1] (see also Jackson, 1996; Stuchtey et al., 2016). This is perhaps particularly the case for fast fashion brands that rely on high volume throughput. Whilst a lot of CE research is focused on materials and resource flows (Braungart et al., 2007), our study draws on an emerging body of literature that explores how businesses incorporate CE principles such as to reduce, reuse, recycle resources as part of their business strategies and operations (Lüdeke-Freund et al., 2019).

Our work as part of the Fostering Sustainable Practices: Rethinking Fashion Design Entrepreneurship project (a collaboration with the London College of Fashion and the Open University) taps into the longstanding notion that mainstream approaches are insufficient to advance CE thinking. And so, we started to explore what (often pioneering) micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in the fashion industry do to advance the circular economy.

In our recently published paper, we showcase how UK fashion MSMEs implement such integrated practices, and set out the range of circular economy practices that these enterprises engage in—such as the use of recycled and recyclable materials, no-waste production, offer of resale and rental services, among others.

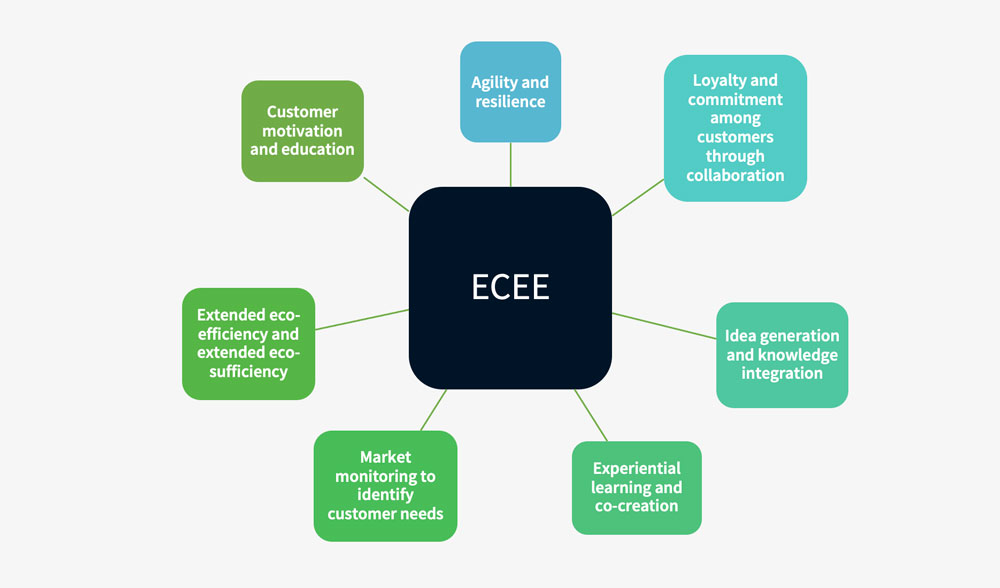

The businesses in our study advance the circular economy for example by engaging closely with their customers in order to influence consumption behaviours as an extension of the business model. To account for such practices, we coin the term extended customer eco-engagement (ECEE) describing customer-facing efforts including communication, educational and co-creational activities. The underlying idea is that business efforts addressing circularity and environmental sustainability must not focus on eco-efficiency alone but need to pro-actively engage with its customers to enable extended resource life.

Our findings suggest that ECEE allows for opportunities in market monitoring, experiential learning, as well as idea and knowledge generation, and thus helps MSMEs develop their dynamic capabilities further (Khan et al., 2020), providing the businesses with even greater agility. Co-creating new products and services with customers reduces market risks for MSMEs because of improved customer loyalty and commitment. ECEE also increases the resilience of the business and safeguards them from unforeseen shocks: we found that fashion MSMEs already practicing extended customer eco-engagement prior to the outbreak of COVID-19 seemed less impacted by the pandemic because of their direct and close links with customers and local communities.

The success of ECEE practice draws attention to the increasingly important role of co-creation with customers and their centrality in value creation (Anderson & Ostrom, 2015) and the need for more extended business-customer activities (Heikkurinen et al., 2019). It is our contention that ECEE, therefore, may constitute an important building block of what Chesbrough and Appleyard (2007) describe as open innovation strategy.

Another noteworthy insight from our research is that fashion MSMEs in our sample showed only limited interest in short-term returns and business growth. Conventional growth ambitions were only pursued when control over the sustainability of products and services as well as wider decision-making processes was guaranteed. That is, in the language of dynamic capabilities (Teece, 2007), growth opportunities were not necessarily being ‘seized’ when MSMEs experienced a gap between those opportunities and their enterprise’s vision and values. This might lead to criticism that sustainable fashion MSMEs’ impact remains comparably low through their limited scalability. However, it stresses their commitment to sustainable business practices with their pioneering CE practices holding potential to contribute to wider, systemic change.

Future research will have to further examine if extended circular economy practices hold the potential to move from so-called weak to strong consumption practices that can lead onto a degrowth path (Lorek & Fuchs, 2013, 2019) while providing opportunities for sustainable prosperity.

References

Anderson, L., & Ostrom, A. L. (2015). Transformative Service Research: Advancing Our Knowledge About Service and Well-Being. Journal of Service Research, 18(3), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670515591316

Braungart, M., McDonough, W., & Bollinger, A. (2007). Cradle-to-cradle design: creating healthy emissions – a strategy for eco-effective product and system design. Journal of Cleaner Production, 15(13), 1337–1348. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2006.08.003

Chesbrough, H. W., & Appleyard, M. M. (2007). Open Innovation and Strategy. California Management Review, 50(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166416

Geyer, R. (2022). The business of less : the role of companies and households on a planet in peril. https://www.routledge.com/The-Business-of-Less-The-Role-of-Companies-and-Households-on-a-Planet-in/Geyer/p/book/9780367755850

Heikkurinen, P., Young, C. W., & Morgan, E. (2019). Business for sustainable change: Extending eco-efficiency and eco-sufficiency strategies to consumers. Journal of Cleaner Production, 218, 656–664. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.053

Jackson, T. (1996). Material Concerns: Pollution, Profit and Quality of Life. Routledge.

Khan, O., Daddi, T., & Iraldo, F. (2020). Microfoundations of dynamic capabilities: Insights from circular economy business cases. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(3), 1479–1493. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2447

Lorek, S., & Fuchs, D. (2013). Strong sustainable consumption governance – precondition for a degrowth path? Journal of Cleaner Production, 38, 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2011.08.008

Lorek, S., & Fuchs, D. (2019). Why only strong sustainable consumption governance will make a difference. In O. Mont (Ed.), A Research Agenda for Sustainable Consumption Governance (pp. 19–34). Elgar.

Lüdeke-Freund, F., Gold, S., & Bocken, N. M. P. (2019). A Review and Typology of Circular Economy Business Model Patterns. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 23(1), 36–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12763

Stuchtey, M. R., Enkvist, P.-A., & Zumwinkel, K. (2016). A Good Disruption: Refining Growth in the Twenty-First Century. Bloomsbury. Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.640

Note

[1] We thank Ian Christie’s recent review of Geyer’s book that both highlights and illustrates Geyer’s conclusions.