What does COVID-19 mean for sustainable consumption?

Our priorities shift when the wolf is at the door, Iona Murphy writes about the impact of the current crisis. It’s quite understandable that people may not have the headspace for sustainability right now. Nonetheless, we’re currently on a hiatus from consumerism—will it last?

Back in the beginning of March, which feels like a lifetime ago, there were signs that the British public might be living more sustainably. 1 in 5 people who fly abroad, commute by car or eat meat were planning to cut back, and expected reductions for clothing and plastic packaging were even higher.

To state the obvious, a lot has changed since then—many of us won’t be driving to work anytime soon, and holidays abroad are off the cards. Our priorities shift when the wolf is at the door, and it is quite understandable that people may not have the headspace for sustainability right now. Even the zero-waste influencers buy plastic in a pandemic.

But there’s reason to think we might act differently when once the dust has settled. We are most likely to change our behaviours during a major life event, like moving house or having a child; COVID-19 imposes such an event on everyone. Change is not always unwelcome; polling for the UK Food, Farming and Countryside Commission found that 6 in 10 adults want to make changes in their life once this is over, whereas only 33% want their life to go back to how it was before. That means almost twice as many adults want change, than don’t.

Life in lockdown has prompted an upswell of community spirit and care; 40% of people feel a stronger sense of community in their area, and 1 in 10 have interacted with a neighbour for the first time. We are remedying the boredom through creative hobbies like arts and crafts, cooking and baking, taking advantage of online courses to pick up a language or instrument. TV viewing is up, but so is reading. 1 in 4 people are exercising more since the lockdown, and 1 in 10 feel fitter. Suddenly we appreciate our time outside and in nature.

All of these might seem like disparate activities, but they share common themes. Maintaining connections (interpersonal and community), doing things for others, learning new things, being active, and having a sense of awareness are the 5 routes to well-being as identified by NEF and recommended by government. Keep these up, we might feel healthier, happier and more fulfilled.

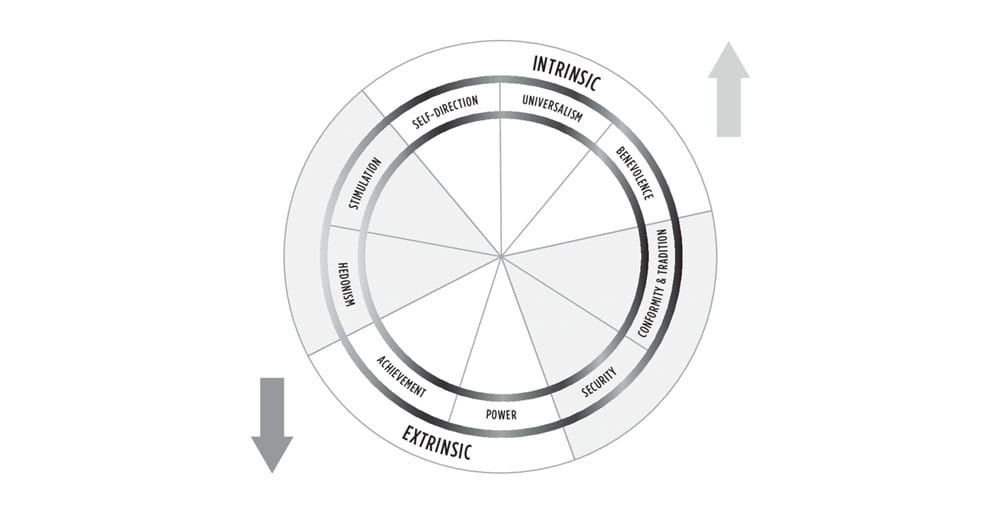

They also represent activities we pursue when acting on what Schwartz identified as our intrinsic values; care for others, bettering ourselves—things we do for their own sake, rather than needing an external reward. These are counter to our extrinsic values, things like financial success, social status and image, which are motivated by the validation of others. Pursing the latter often requires us to buy things that aren’t essential, whereas many intrinsically-focused activities have a lower carbon cost. So, it has been suggested that increasing the amount of time we spend on intrinsically-focused activities is a path to consuming more sustainably: if you spend your weekends learning Spanish, rather than shopping, your impact is reduced.

Each one of us possess both sets of values, they are constantly in flux within us. However values that are directly opposed (like extrinsic and intrinsic) can have the interesting effect of suppressing the other when one comes to the forefront (and vice versa), at least for a short while. The shift in emphasis towards the intrinsic values of care and community echoes across society, through individuals, a good deal of businesses, and in certain respects our government.

Much depends on whether we continue to emphasise intrinsic values long-term; Sunday’s announcement by the UK Government already suggests a shift away from these from government. However, COVID-19 has laid bare the failings of our welfare system and a mass reliance on state support could force a rethink. Maybe the idea of a universal basic income (as Spain are moving to implement) is more palatable to a Conservative government when it looks like pragmatism, rather than socialism. Such a change would have the knock-on effect of reducing inequality, which has been proposed would reduce material consumption. Fundamental questions such as how we measure progress may be up for debate in a way that may not have been considered before—for example, the city of Amsterdam will put Kate Raworth’s doughnut economic model at the heart of its post-COVID strategy.

A cultural and institutional emphasis on intrinsic values provides more fertile ground for the diffusion of sustainable consumption principles because it validates decision-making from a wider-than-self perspective as normal, and can even quiet our extrinsic drives. This is not to say that we’ll awake from consumer hibernation and take an immediate U-turn when it comes to what we buy. But it does mean that the notion of what is essential (be that an essential job, essential purchase, essential policy) is salient to everyone in a way it couldn’t have been before COVID-19. How well-remembered this will be depends on the tone that government and businesses set.

Each industry is facing its own set of challenges post COVID-19, and so also a distinct set of possibilities for the future of sustainable consumption. It would be impossible to review them all, so let’s take fashion as an example. On the one hand, coverage regarding brands’ treatment of overseas suppliers and any economic fall-out in manufacturing-dependent markets may go some way to de-fetishising commodities in the public eye, giving goods a sense of materiality that branding works hard to disguise. With job losses already hitting and recession looming we might cut back on non-essential purchases, or have less money available to spend. When it comes to our carbon footprints, those on lower incomes are more sustainable consumers by default. Knowing clothes must last, we might consider buying fewer, better clothes or even second-hand clothes (hence beginning to adopt a ‘slow fashion’ ethos).

This is not to be naïve, though. Times of crisis have the potential to turn us inwards, making us less responsive to far-away issues, whether they are temporal (the climate crisis) or geographical (what’s happening to garment workers). After 2008’s recession brands and government asked us to spend our way back to normality, and we did, forgetting to correct our mistakes along the way. The media firehose of messaging telling us to buy things has been reduced to a trickle for the time being, but it will switch on again at some point. There will be a glut of unsold products offered at a discount price, and shoppers will want to keep continuity with fashion-forward identities. People have less disposable income in a recession, so the idea of paying a premium for ethically sourced products is unrealistic. Many of the smaller retailers selling sustainable fashion won’t weather the next few years, shrinking the market for ethical goods.

What hurts one industry may boost another. Some degree of restriction on movement will be in place until a vaccine is found, meaning there will be a hole in our leisure time that travel and experiences would have filled. It’s very likely that the role of fast fashion will even be amplified in terms of its importance to identity, relaxation and entertainment. Social media fuels fast fashion by transforming mundane occasions into public spectacles; we feel embarrassed to be seen in the same thing twice. Fast fashion brands have been pushing a loungewear aesthetic throughout the COVID-19 crisis, something which Boohoo (parent brand to several fast fashion stores) attributed to a year-on-year increase in sales for April. We don’t need to leave the house to need a new outfit.

Surge in sales of onesies notwithstanding, it is still feasible our brief hiatus from consumerism will have a long-lasting impact on how we spend our time and money. Opposite trends can and do exist in parallel; some people will buy more, because they want to feel normal. Many people will buy less, because they have to. But those who carry on pursuing activities driven by their intrinsic values (the routes to psychological and physical well-being) may simply not feel the need to buy as many things, as they have other ways of finding amusement and fulfilment. They may not even notice this is happening, their focus having shifted elsewhere.