Tackling growth dependency—the case of adult social care

Christine Corlet Walker and Tim Jackson

CUSP Working Paper Series | No 28

Executive Summary

Our current economic system depends on growth to function effectively. Several recent reports have aimed to understand this growth dependency and have sought ways to mitigate it. In light of the long-term slowdown in the growth rate already witnessed in advanced economies and the potential threats to economic growth from climate change, biodiversity loss and social disruption, such strategies are fully consistent with economic prudence.

In many ways, the UK’s adult social care sector represents a microcosm of the growth dependencies observed in the wider economy. The rising demand for adult social care associated with an ageing population creates a dependency on ever-growing production of health and social care services. Rising costs, related to the time-intensive nature of social care, demand growing revenues for care companies to stay afloat. And the use of predatory financial practices by investment firms places unmanageable ongoing financial costs on large parts of the sector.

These growth dependencies can be attenuated or aggravated by physical, financial, legislative, and social factors. The privatised structure of adult social care, combined with an absence of effective financial legislation, creates the conditions that expose care companies to overleveraging, among other risks. Tackling these underlying structures—e.g. through strict financial regulations—would not only reduce the growth dependency of the adult social care sector but would also generate other co-benefits, such as reduced inequality.

The processes and structures creating growth dependency in adult social care apply to other parts of the welfare state too. In this report, we therefore present a systematic approach to identifying, analysing and transforming growth dependencies in the welfare state. Using adult social care as our case study, we explore how growing demand, rising costs and rent seeking can create growth dependencies. We analyse the structures that drive and reinforce these growth dependencies and, in so doing, we identify fruitful levers for transformation and mitigation.

The systematic application of this framework to all parts of the welfare state would enable us to protect the resilience of the welfare state and improve the wellbeing of UK citizens, no matter what is happening to growth. Specifically, this report calls on HM Government:

- to establish a formal inquiry into growth dependencies across the welfare state and to develop a precautionary strategy for mitigating the risks that arise from them.

In relation to the adult social care sector, the paper recommends that HM Government should:

- accelerate proposed reforms to adult social care and expand their remit urgently to address the pressures created by rising demand, rising costs and rent-seeking behaviours;

- enact legislation to protect the wages of care sector workers and the quality of social care against predatory financial practices;

- develop and support innovative ownership models that break the link between property speculation and the financial stability of the adult care system.

1 | Introduction to growth dependency

In the years since the Second World War, advanced economies such as the UK have developed strong public sector social welfare systems. Typically, such systems have been supported by taxation on incomes, profits and consumption spending. The fiscal viability of social welfare has, as a result, come to depend on the pursuit of growth in the gross domestic product (GDP), which in its turn has become a default policy goal of governments across the world. In short, and in spite of the many acknowledged limitations of the GDP as a measure of welfare,[1] modern economies have become ‘growth dependent’ in the sense that certain core aspects of human wellbeing become compromised when, for whatever reason, growth in the GDP is either hard to come by or is undesirable.

As productivity growth rates in advanced economies have declined, for instance, reliance on the fiscal position has placed aspects of welfare such as the provision of adult social care under increasing financial pressure. Acute economic and fiscal conditions such as those experienced following the 2008 financial crisis and during the Covid-19 pandemic have exacerbated this situation further. Attempts to ‘rescue’ the adult social care sector through privatisation have failed to prevent what many have now acknowledged as a deep ‘crisis of care’.[2]

The crisis in adult social care is a particular case of what has become known as the ‘growth dependency’ of the modern economy. The need to address this phenomenon is now widely acknowledged. For instance, an opinion paper from the European Economic and Social Committee published in 2020 argues that the transition to a wellbeing economy must start by adopting a ‘precautionary approach’ in which social stability does not depend on GDP growth.[3] A group of 238 academics across Europe recently penned an open letter calling on governments to ‘end the growth dependency’ of the European economy.[4] A petition on the same theme has so far received more than 90,000 signatures.[5] The European Parliament held its first Post-Growth Conference in September 2018 and will hold a second later this year.[6] Calls to reduce growth dependency have also drawn support from a recent report to the German government which advocated a precautionary ‘post-growth’ approach to achieving social wellbeing within planetary boundaries.[7] The report called for policies which are ‘future-proofed’ against the possibility that economic growth might not be achievable in the same way that it has been historically, particularly if key environmental and social goals are to be met.

In recent policy briefings, the APPG on the Limits to Growth has already highlighted some of the causes and consequences of growth dependency. We have explored the long-run stagnation in productivity,[8] addressed the social consequences of this trend[9] and worked to establish the foundations for a wellbeing economy. We have also identified the need to unravel the powerful forces that lock us into the pursuit of growth in the GDP and to devise ways to address it.[10] The aim of this working paper is to report on recent work advancing this aim, by developing a systematic framework for tackling growth dependency, illustrated through the particular case of adult social care.

2 | Background

What would a precautionary post-growth approach mean for our welfare systems? How do our welfare systems depend on economic growth today? And what can we do to reduce that dependency? These questions prompted us to engage in a thorough review of the literature[11] and a series of expert interviews with academics, policy makers, and welfare state practitioners. The study revealed a number of key threads.

Respondents identified the challenge of delivering welfare in a postgrowth context as being primarily about meeting the needs of the population within the means of the planet. As new social needs have emerged over time, driven by demographic and socio-economic changes, economic growth (and growth in resource use) has helped to meet those needs, albeit unequally and unevenly over time. As growth rates decline, it is likely that an imbalance between rising demand and limited resources will require an innovative restructuring of the welfare state.[12] This throws up questions about what a postgrowth welfare structure would look like, about the degree of redistribution required to achieve wellbeing for all, and about the ethics of living on a finite planet. Work to address these issues has variously focused on imagining equitable, preventative, low-carbon, and relational welfare systems. Small scale experiments in ‘radical help’ have demonstrated the possibilities of doing things differently, from organised networks of older people in South London tackling the loneliness epidemic by drawing on their wealth of skills and experience to provide comradery and practical support to one another,[13] to communities in East Surrey actively creating local conditions that foster good health.[14] These case studies offer windows into what postgrowth welfare might mean, in practice.

Concerns about maintaining macro-economic stability and ensuring continued funding for the welfare state in a postgrowth context were also at the forefront of the issues illuminated. In particular, experts focused on the perceived fiscal reliance of the welfare state on tax revenue, and the potential for those revenues to stagnate or decline (all else equal) as growth becomes harder to come by. There have been two approaches to grappling with this issue. First, new modelling techniques are being used to explore possibilities for achieving macro-economically stable and ‘socially sustainable’ post-growth futures[15]. Many of these novel techniques can better cope with the path-breaking shifts required to transition to a postgrowth economy than more traditional approaches.[16] They have already been used to dispel many of the myths about growth-based economies, including the feasibility of meeting our climate change targets if we rely on technological solutions alone,[17] and the necessity of growth to prevent rising inequality.[18]

The second way to think about the challenge of potentially stagnating tax revenues is to look at the political context. The government always has the option of maintaining tax revenues by increasing tax rates. This could be achieved through progressive taxes on wealth, on ecologically damaging goods, or on land, for example. However, respondents also argued that the the state continually finds itself torn between two conflicting interests. On the one hand, a powerful and wealthy elite lobbies government to protect its ability to accumulate capital. On the other hand, government holds a fundamental responsibility to supporting those in need by providing a well-functioning social safety net.[19] This emphasises the likely importance of soft factors such as power, inequality and social norms in determining the outcomes associated with a precautionary postgrowth position. Who are the pro-growth lobbyists and what narratives will they leverage in favour of this position? How strong are workers’ rights and to what degree will they be able to demand a fair and just transition? Even if we demonstrate the macro-economic possibility of a prosperous future without economic growth, these are the issues that will determine what that future looks like in reality, as growth rates decline.

Lastly, experts and authors emphasised the multiple ways in which the structure of the welfare state itself creates growth dependencies. In particular, they looked at the challenges associated with the embedding of profit-oriented incentive structures in sectors like health and social care. Take the largely-privatised pharmaceutical sector, for example. The drive to maximise profits has led to the priority development of commercially attractive drugs that have little additional therapeutic value to those already on the market. This is met with a corresponding neglect of socially beneficial but less profitable drugs, such as those aimed at tropical diseases. The competitive market setting further incentivises the expenditure of “enormous sums” of money on marketing[20] and stock buy-backs[21], in an effort to maintain market share. Similar kinds of ‘dysfunctional’ market dynamics that prioritise financial over social goals can be observed in other privatised parts of the welfare state too, including social care, prison management, and transportation. The presence of supply oligopolies, lengthy drug patents and informational asymmetries all serve to distort market prices and give providers market power over consumers. These mechanisms, among others, increase the cost of welfare for governments and consumers, and make continued growth not only a feature of the system, but a necessity.

The reflections of interviewees, combined with insights from the literature, have simultaneously highlighted the breadth of the challenge of overcoming growth dependency, whilst also offering entry points for change. Many of the proposed changes would deliver other benefits to the welfare state, beyond a reduction in growth dependency. Indeed, pursuing preventative, localised and relational models of welfare would align with the aspirations outlined in Public Health England’s recent report on inclusive and sustainable economies.[22] It is from this understanding of the significant but surmountable task of overcoming growth dependency that we turn to the question: how do our welfare systems depend on economic growth?

3 | How do our welfare systems depend on economic growth?

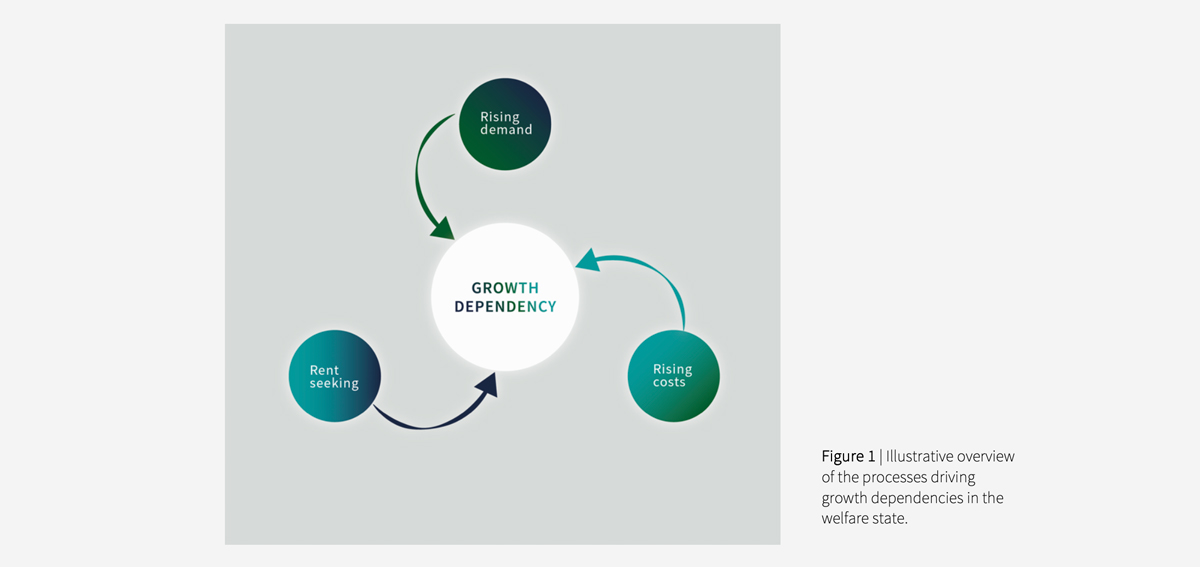

The starting point for any attempt to tackle growth dependency is to establish precisely the mechanisms through which this dependency arises. Building on the background work, we have identified three core processes that drive the welfare state’s dependence on growth (Figure 1). These are: 1) rising demand for welfare; 2) rising labour costs; and 3) rent-seeking. We discuss each in turn below, highlighting what kinds of policies we can look to for solutions.

Rising demand

As society progresses and changes, demand for welfare services changes with it. Where demand is rising as a result of long-run socio-economic trends[23]—such as aging, declining fertility, or increasing material intensity of production—this can create a dependence on growth in the production of goods and services that meet these new demands. In particular, if growth in aggregate welfare demand outstrips growth in labour productivity (how time efficiently we produce goods/ services) and material efficiency, then we will need to increase labour and material inputs respectively in order to meet the growing demand.

This growth dependency is particularly visible in the adult social care sector. Between 2015 and 2035, the number of older adults with complex, high dependency needs is projected to almost double.[24] By contrast, since 1997, labour productivity in the care sector has declined by more than 10%.[25] These unfavourable trends have likely combined with austerity over the last decade to deepen the ongoing retrenchment of welfare services. Indeed, we know that the number of residential home beds per older adult declined by 15% between 2012 and 2020,[26] and 1.5 million adults in the UK over the age of 65 now have some level of unmet care needs.[27] This highlights the negative impacts of the growth dependency dynamic.

The material and carbon footprints per unit output of goods and services produced can also change over time. If these increase, so too does the level of inputs required to deliver welfare services to a given population. Consumption is a socially constructed act, meaning that the ways that we use and consume goods can be considered specific to certain time-periods and cultures. Changes in the material and carbon intensity of goods and services over time, therefore, are largely determined by shifts in culture, technology, infrastructure and socio-economic context.[28]

For example, Covid-19 has altered the physical and social infrastructure of adult social care, from the medical equipment required to keep patients safe, to the means through which families interact with their loved ones living in care homes. In particular, the enhanced need for personal protective equipment for staff has increased the per-patient carbon footprint of social care services in the UK.[29] These socio-economic changes (to legislation, professional best practice, and social norms) have created a dependency on growing material, carbon and labour inputs into the production of adult social care, in order to avoid adverse health outcomes for residents and workers in the sector.

Understanding this growth dependency in terms of both its demand and supply side dynamics can help to identify a number of potentially effective options for mitigation. On the demand side, policy can look to reduce demand for adult social care by taking a more preventative approach to social policy.[30] On the supply side, the government might consider strategies aimed at developing alternative modes of delivery that are localised, low-resource, and relational.[31] This could involve retraining workers from high-carbon industries for roles in the green and caring economy.

Rising costs

Productivity grows more quickly in some sectors than others. As a result of the rapid growth in productivity in some sectors (e.g. many manufacturing industries), average wages in the economy rise. This pushes up the relative cost of labour in those sectors with lower rates of productivity growth (e.g. the arts, certain public services), as firms struggle to increase wages in line with the national average, to avoid a migration of employees towards sectors where they could find better pay.[32] Evidence of these dynamics has been found across public services in many countries, with the UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility noting in 2013 that it had led costs in many public services to “rise relative to other sectors”.[33]

This has certainly been the case for adult social care. The time-intensive nature of care work means that there are limited opportunities for achieving cost efficiencies through labour-saving technologies, without compromising quality of care. We also know that there are only modest opportunities for economies of scale in the sector.[34] In this context, constraints on revenue (e.g. if government budget restrictions lead to an effective cap on prices) can leave firms with few options to meet rising labour costs.[35] At the time of the introduction of the National Living Wage in 2016, The Resolution Foundation reported employers’ claims that there were “few choices other than to absorb the cost because of the inability of the sector to improve productivity without worsening the care provided to service users”.[36]

This draws on the idea that firms have a limited number of things they can adjust when they are faced with a new cost. For example, if the wage bill increases, firms can look to: a) increase the prices they charge for their services; b) invest in labour saving technologies; c) find other non-wage cost savings; d) reduce the dividends they pay to shareholders.[37] Hence, when wages rise in a sector that is both price-constrained (can’t adjust price) and has low potential for labour productivity growth (can’t readily achieve labour savings), providers’ margins are progressively squeezed, and they must instead look towards non-labour costs—including factors that impact working conditions and quality of care—and profits for savings. The same principle holds true for other cost pressures, such as onerous debt payments and intense inter-firm competition.

If the increasing relative cost of public services continues over the long term—which we might expect since the scope for labour productivity gains in many public service sectors is limited[38]—then in order to even maintain the same level of public services, the government would need to divert a progressively greater proportion of its expenditure towards these services. This holds true even without accounting for any growth in needs or any desire to provide better services over time. This does not mean that public services like healthcare and social services will necessarily become unaffordable in either a growth or post-growth future. That will depend on political decisions about the allocation of public funds, the scope and structure of taxes, and what proportion of the economy is made up of these less productive sectors. However, the growing relative cost of certain public services will likely intensify the distributional conflicts faced by governments as they make decisions about the allocation of resources, therefore creating a political dependency on ongoing macroeconomic growth.

Widening our lens to the broader economy, there is one more challenging dynamic created by the pursuit of productivity. If worker productivity increases on average across the whole economy (i.e. if the average hourly output of the workforce increases), then the economy will have to grow and produce more goods and services in order to keep the same number of people employed. This dynamic is known as the ‘productivity trap’.[39] It is partly driven by the continued ability of rentiers (owners of capital) to capture the benefits of increasing productivity, instead of passing those benefits onto workers in the form of reduced working time, as economist John Maynard Keynes once expected would happen. In his essay on the Economic Possibilities of our Grandchildren, Keynes predicted: “we shall endeavour to spread the bread thin on the butter-to make what work there is still to be done to be as widely shared as possible”.[40] Instead, and particularly over recent decades, the gains of productivity growth have gone towards expanding production outputs, reducing prices for consumers, and increasing profits for rentiers.

Improving workers’ rights and regulating service quality can both help to guard against the negative impacts of the growth dependencies created by the pursuit of labour productivity, protecting workers and service users. Moving away from for-profit modes of service delivery can also mitigate these dependencies by removing some of the conflict between profit, wages, and non-labour costs. However, these actions do not address the core reliance on increasing revenues to meet rising costs in time-intensive sectors, or the need to grow the broader economy to maintain employment. To address these issues, we must consider policy actions that redistribute the gains from productivity growth more equitably by taxing the owners of capital or by reducing working hours. These actions would seek to reduce the wage differential between sectors and mitigate the need for the wider economy to grow its outputs in perpetuity.

Rent seeking

Rent seeking is the use of time and resources to secure monetary compensation in excess of, or disproportionate to, the labour invested by the recipient.[41] This can be achieved through many means, including lengthy intellectual property patents, lobbying for favourable policy, high rental charges, the use of tax havens, etc. Certain rent seeking strategies can leave firms dependent on growing revenues to mitigate distributional conflicts between returns to investors and other costs, and/ or to avoid adverse impacts such as bankruptcy.

Turning once again to adult social care, debt-leveraged buyouts are a common tool used by investors to engineer a higher rate of return on their investment.[42] In short, an investment firm might buy a target social care company using a large proportion of debt, and only a small proportion of their own capital. This means that the capital structure of the target company just after acquisition is skewed heavily towards a high proportion of debt and low proportion of equity. Over the course of the investment horizon, then, the target company’s cash flow can be used to service and repay the debt. As this happens, the equity portion of the company’s capital structure gradually increases. Through this process, investors can earn a greater rate of return on their investment than if they had bought the company using equity alone.

Three of the five largest care home chains in the UK have been subject to a debt-leveraged buyout in the last 10 years, managing a combined 30,000 beds between them.[43] Where large quantities of debt have been taken on by a firm, interest payments can absorb a significant portion of revenues, coming into direct conflict with shareholder profits, wages, and non-labour costs. In 2019, a forensic accounting analysis found that, in the five largest private equity owned care home chains, “16% of the weighted average weekly fee” for a residential care home bed went towards interest payments.[44] Further, recent research suggests that debt-leveraged buyouts increase risk of bankruptcy for the target firm by approximately 18%.[45] In this context, growth is not a choice but a necessity to ensure sufficient cashflow to continue to cover the extraordinary ongoing costs associated with these financial practices and others.[46]

Industry surveys indicate that expected rates of return on investment of 12% or more have been the norm in adult social care for decades[47]—rates that are more common in highly volatile, cyclical industries. This is significant because the higher the expected return, the more firms’ margins are squeezed as labour (and other costs) come directly into competition with returns to investors. As a recent report by Diane Burns and colleagues stated: “if the cost of capital were substantially less than 12%, the fair price [for care] would be substantially lower, or wages (as the other major cost) could be substantially higher”.[48] Moreover, high expected returns encourage investors to use the kinds of risky financial practices named above, alongside others (e.g. asset stripping, onerous rental costs, use of tax havens, etc.), to increase their rate of return in the short-term.

Asset stripping, for example, offers one of two potential benefits in terms of investor returns. First, if the care home properties are sold to an external third party, care home owners gain a large quantity of cash up front, which could either be used to pay special dividends to shareholders, or to rapidly expand the business. Alternatively, if the properties are bought by a related company (one that is owned by the same ultimate parent company), it enables the owners to extract cash from the operating business on an ongoing basis, by charging high rents, especially if that company is registered in a tax haven. The flip side, of course, is that this strategy reduces the financial flexibility of the core care company through asset impoverishment, whilst adding further financial costs to its balance sheet in the form of high rental payments. This once again gives care home managers no real choice but to pursue a growth-based strategy in order to abate these financial pressures.

The knock-on effects of these financial engineering practices are substantial. The 18 largest for-profit social care providers spend “£11.07 out of every £100” of income on rent, where the eight largest not-for-profit providers spend just £2.34.[49] This is money that could arguably otherwise be spent on frontline service delivery. Further, media reports around the time of the collapse of Southern Cross in 2011 and the movement of Four Seasons into administration in 2019 link these events to the companies’ high debt burdens and onerous rental demands from external landlords.[50] Southern Cross employees even reported that “the company had cut spending on the physical environment, to the extent that several homes… had been “run down to rack and ruin”.[51]

These kinds of growth dependencies can in theory emerge in any part of the welfare system that has been privatised. And there is already evidence that the financial practices driving these growth dependencies are being applied in children’s services,[52] the prison system[53] and parts of the publicly funded R&D sector, such as academic publishing.[54]

Beyond firm-level dynamics, rent seeking also creates a strong political dependency on growth. This dependency becomes clear when we remember the tension within the state highlighted by some respondents in our study. Enabling the wealthy to continue to accumulate wealth (e.g. through tax cuts and deregulation) stands in contrast to the role of government in supporting those in need by providing a well-functioning social safety net (e.g. through adequately funding welfare services).[55] Economic growth enables the government to meet both of these goals without sparking significant distributional conflicts, for example, by dramatically increasing tax rates. However, as economic growth slows, comes to a standstill or even goes into reverse, these two aims come increasingly into conflict. This conflict manifests itself in what appear to be intractable political choices between adopting redistributive measures, enacting welfare retrenchment and/or increasing public debt. As we shall discuss in future work, this dynamic may be either intensified or relieved by the political ideology of money. But what is clear is that the more individuals are able to pursue economic rents—e.g. through lobbying for tax cuts and deregulation—the stronger this growth dependency will be.

Broadly speaking, therefore, overcoming the growth dependencies created by rent seeking requires finding ways to “diffuse rentier power, discourage rent-seeking and redistribute rents”.[56] This can be achieved by targeting the specific sector of concern (e.g. legislation prohibiting debt-leveraged buyouts in adult social care), or by improving the wider financial environment (e.g. by actively pursuing tax on offshore structures). With the latter more likely to impact the political growth dependency created by rent seeking. Beyond regulatory or legislative initiatives, changes in ownership structure (e.g moves towards community, employee or public sector ownership) would also reduce the dynamics of rent seeking and alleviate growth dependency.

4 | A framework for change

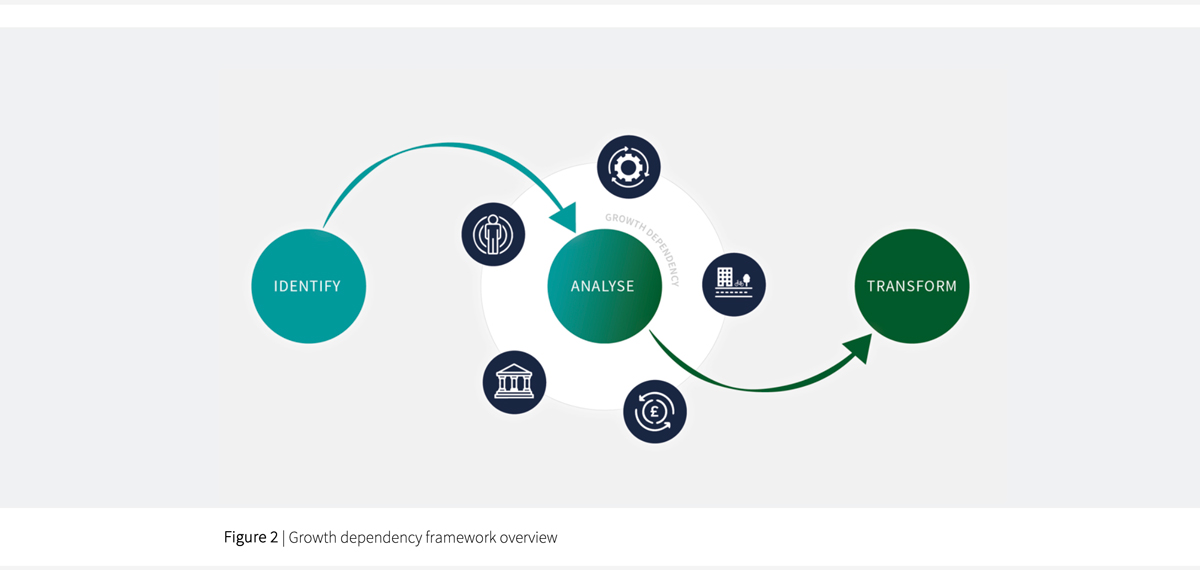

Having established the processes by which growth dependencies can emerge within the welfare state, in this section we present a three-stage framework for identifying (Stage 1), analysing (Stage 2) and transforming (Stage 3) those dependencies (see Figure 2). The aim of the framework is to create a systematic and replicable approach to this challenge. It is designed to be applied at the sector-level, supporting the development of sector-specific policy proposals that both mitigate the negative consequences of growth dependency, and identify ways of ultimately moving towards a precautionary postgrowth position.

To illustrate the operation of this framework, we adopt the growth dependency created by debt-leveraging in adult social care as an illustrative example. In the following paragraphs, we highlight how rent seeking combines with sectoral characteristics to create and reinforce this growth dependency within adult social care. However, it is worth remarking that the framework would ordinarily be applied holistically, considering how each of the processes outlined in Section 3 above might generate growth dependencies for a chosen sector.

It is also worth noting here that we use the term growth dependency to include both micro and macro level dynamics; from a firm-level need for growth in revenues, and sector-level requirements for growth in production inputs (such as labour, materials and energy), to a macro-level dependence on growth in GDP. Each of these dynamics encourages the system to grow in perpetuity and, as such, they should be examined in their own right.

Stage 1: Identifying growth dependencies

The first stage of the framework involves selecting a particular welfare sector (e.g. education, prisons, adult social care) and reflecting on the relevance of rising demand, rising costs and rent seeking for that sector. Is demand in the sector increasing over time, and why? How labour-intensive is the good or service being produced in the sector? What scope is there for increasing productivity? Where are the opportunities for rent seeking practices to be used in the sector? What evidence is there that this is happening?

This task first requires some targeted descriptive work, creating a clear profile for the sector of interest that will support the analyses in this and following stages of the framework. For this, we draw from political economic thinking, focusing on identifying the relevant individuals, companies and institutions, and their relationships to one another in terms of power, influence and money. Information about the structure of the sector, its workforce, service users, and ownership patterns, as well as relevant details about the financial and market structures, and the policy and regulatory environment, can all be used to support a rich and systematic analysis of growth dependency.

Turning to the example of adult social care, we find that 84% of beds in residential and nursing homes are managed by private companies,[57] and are therefore vulnerable to rent seeking. Further, approximately 12% of beds are already managed by companies owned by investment firms,[58] making them particularly vulnerable to rent seeking through predatory financial techniques. In practice, as discussed in Section 3, we know that three of the five largest care home chains in the UK have been subject to a debt-leveraged buyout. This places these companies and their residents at increased risk of insolvency. In the care sector, this risk carries with it potentially significant social ramifications. In addition to the loss of jobs associated with insolvency of such large companies, there may also be negative physical and psychological impacts on vulnerable service users—particularly for those with complex needs—who have to be moved unexpectedly to another home.[59] Now a decade on from the collapse of Southern Cross in 2011, with the loss of 31,000 beds, residents in adult care homes remain vulnerable to the financial instability of service providers.[60] These findings illustrate the existence of rent seeking using debt-leveraging and highlight the potential for negative impacts associated with the resulting growth dependency.

Stage 2: Analysing growth dependencies

The processes described in Section 3 above explain how adult social care depends on growth. Growth dependencies, however, do not emerge in a vacuum. They are created, supported and driven by a series of underlying structures. We therefore turn our attention to the question of why the care sector depends on growth. What perpetuates growth dependency? The second stage of the framework aims to answer this question.

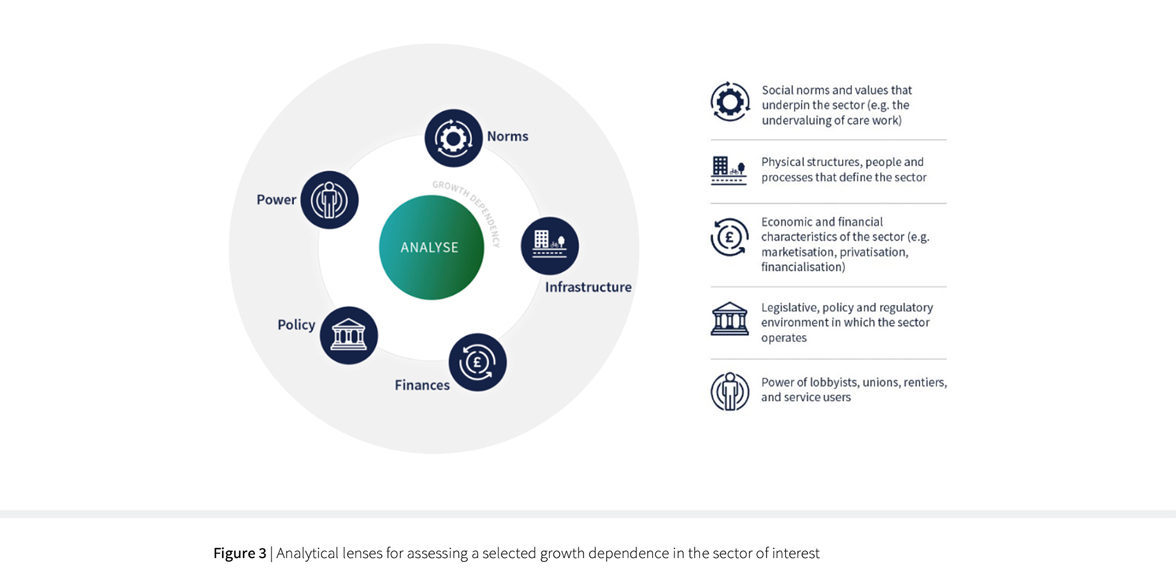

Specifically, we consider the social and structural factors that underpin and drive the growth dependencies in a particular sector or context. This requires us to look beyond proximate causes—such as the over-indebtedness of key players—and analyse the forces that give rise to them. It requires attention both to ‘hard’ drivers such as physical infrastructure and to ‘soft’ drivers such as societal norms. With this in mind, in the paragraphs below we briefly evaluate our selected growth dependency through the five core analytical lenses shown in Figure 3:

1) Finances

The privatisation of care creates the opportunity for investment firms to enter the sector, and bring with them financial techniques targeted at achieving a rapid return on investment (e.g. debt-leveraged buyouts). A significant portion of the social care market is vulnerable to this form of rent seeking as more than eight out of ten residential and nursing home beds are managed by private companies[61], and 12% are already owned by investment firms[62].

2) Infrastructure

This potential for growth dependency through onerous debt is exacerbated by the physical structure of the care sector, which facilitates the use of large property-backed loans, designed to achieve rapid returns on investment, and secured against the care home companies’ physical assets.

3) Policy

A notable absence of legislation detailing what constitutes appropriate and responsible levels of debt for the sector aggravates these dynamics. It leaves care home companies exposed to over-leveraging and facilitates the excessive prioritisation of financial over social goals within the sector.

4) Power

Power asymmetries between the owners of care homes and those delivering and receiving care also plays an important part in the story of growth dependency. For example, the potentially large physical, emotional and financial costs associated with moving from one care home to another mean that consumers within the adult social care market cannot easily express their preferences between different care providers. The existence of this immobile consumer enhances the ability of care home owners to pursue profits—even where this might be at the expense of quality of care[63]—without being heavily penalised by falling occupancy rates. The much-vaunted ‘benefits’ of the free market no longer hold.

5) Norms

Finally, it is clear that a historical devaluing of care work and a lack of political prioritisation of the care sector has reinforced the conditions for profiteering, even where this has come at the expense of carers’ wages and working conditions.[64] Evaluating the growth dependence in this way emphasises the pillars that underpin it and allows us to more easily identify opportunities for mitigation.

Stage 3: Transforming growth dependencies

The point of this deeper analysis is to put policymakers in a stronger position to identify effective levers, able to transform the conditions under which social care operates. The third stage of the framework therefore draws on the analysis of drivers from Stage 2 to identify policy options to support the move towards growth independence.

Specific policy levers will vary from sector to sector. However, throughout Section 3, we began to draw out some of the broad levers that are likely to be effective in reducing growth dependencies across the board. These include: investing in preventative models of social policy; making sustainable, low-resource options available for individuals to meet their needs; putting the necessary policies and protections in place to support reduced working time; promoting the creation of jobs in the green and caring economies, including training opportunities for workers looking to transition from high-carbon industries; shifting towards models of welfare delivery that better balance social and financial goals (e.g. social enterprises); and reducing the ability of rentiers and investors to continue to extract value from welfare services. This list of policy options shows that tackling growth dependency can generate a range of environmental and social co-benefits too.

Returning to debt-leveraging in the care sector, several potential policy levers emerge from our Stage 2 analysis (these are not exhaustive, but rather illustrative):

- Innovative ownership models. These could be used to limit the pursuit of profits (e.g. by transitioning towards social enterprise structures), or to break the link between the property structure of the care homes sector and the use of predatory financial practices (e.g. by using a public land trust approach[65]).

- Financial regulation. This would aim to limit the ability of care home companies to pursue unsustainable financial structures. For example, government could establish responsible debt standards for the sector, and/ or minimum provider liquidity and capital adequacy requirements.[66]

- Non-profit care providers. A transition to a completely non-profit care sector, made up of social enterprise, voluntary and public sector providers would remove opportunities for rent seeking through financial engineering altogether.

At this point it is sage to consider these policy options in terms of problematic path dependencies (i.e. factors that might impact or hinder the implementation of the proposed policy) and likely spill over effects (i.e. positive or negative unforeseen impacts on other sectors). Considering again the growth dependency created through over-leveraging, the first and arguably most difficult path dependence is the size of existing debt burdens for some social care companies.[67] Since loan covenants for certain types of debt prohibit—or come with a large fee for—early repayment, any proposals aimed at reducing the role of debt in the sector would need to be paired with suitable debt-forgiveness and/ or structured repayment processes.

Further, any proposals to tighten debt regulations in adult social care would likely reduce private investment in these sectors, as investment firms see a narrowing opportunity for rapid returns. Possible impacts on public finances—tax rates, allocation of funding between different public services, etc—would therefore need to be carefully evaluated, and complementary programmes supporting responsible, low-cost lending to small and medium sized care homes companies considered.[68] On the flip side, the implementation of effective financial regulation would also have positive spill-overs, impacting all sectors of the welfare state where onerous debt is a problem (e.g. children’s services). This highlights the potentially far-reaching consequences of tackling growth dependencies in the adult social care sector alone.

Once policy levers have been identified and evaluated, the final task is a synthetic one, assessing synergies and conflicts between policy proposals. A broad programme of work—applying this framework systematically to investigate the impacts of rising demand, rising costs, and all forms of rent seeking—would support this task and help to create a coherent policy approach to reducing growth dependencies in adult social care.

Conclusions and recommendations

Growth dependency is not something that can be ignored. But, as we have argued in this report, it is something that can be systematically tackled. We have explored how growth dependency impacts the adult social care sector today, with pernicious consequences. And we have shown how a systematic approach to identifying and analysing growth dependency in adult social care, and elsewhere, can enable us to find effective levers for transformation. The discussion of adult social care presented here is not intended to act as a comprehensive guide to tackling growth dependence in the sector. Rather, it is used to illustrate the principles at work, and to demonstrate how we might begin to conceptualise and tackle these challenging dynamics. In particular, we have found that reducing rent seeking not only lessens the growth dependence of the care sector, it can also be implemented in a way that delivers significant additional gains, ranging from improved public accountability and cost efficiencies to better working conditions and reduced inequality. In this way, a transition towards ‘growth independence’ emerges as more than just a precautionary position: it is also a desirable one.

In relation to the adult social care sector, this report recommends:

- accelerating proposed reforms to adult social care and expanding their remit urgently to address the pressures created by rising demand, rising costs and rent-seeking behaviours;

- enacting legislation to protect the wages of care sector workers and the quality of social care by limiting the potential for predatory financial practices;

- exploring the potential for innovative ownership models that break the link between the property structure of residential care homes and the financial stability of the adult care system.

Beyond these specific sectoral reforms, this report argues that Government should:

- establish a formal inquiry into growth dependencies across the welfare state and develop a precautionary strategy for mitigating the risks that arise from them.

The growth dependency of modern economies creates fragilities in the provision of societal wellbeing under any conditions in which economic growth is either infeasible or undesirable. Under these circumstances, it is prudent for policymakers to develop a systematic process that can be used to understand and mitigate social risk and to create more resilience in the welfare functions for which government is responsible.

Exploring and articulating these strategies clearly requires a degree of political will and an openness to the idea that building a precautionary ‘post-growth’ position is a meaningful, pragmatic and achievable task. But in the light of the long-term slowdown in the growth rate already witnessed in advanced economies and the potential threats to economic growth from climate change, biodiversity loss and social disruption, such a strategy is fully consistent with economic prudence.

Knowing how best to ensure continued social wellbeing in a post-growth environment is essential, particularly when growth itself can no longer be taken for granted.

Notes

[1] Corlet Walker, C and T Jackson (2018). Measuring Prosperity—navigating the options. CUSP Working Paper No 20: https://cusp.ac.uk/themes/aetw/measuring-prosperity/.

[2] See Dowling, E (2021)The Care Crisis—what caused it and how can we end it? London: Verso; Bunting, M (2020) Labours of Love—the crisis of care. London: Granta.

[3] https://www.eesc.europa.eu/en/our-work/opinions-information-reports/opinions/sustainable-economy-we-need-own-initiative-opinion

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/sep/16/the-eu-needs-a-stability-and-wellbeing-pact-not-more-growth

[5] https://you.wemove.eu/campaigns/europe-it-s-time-to-end-the-growth-dependency

[6] https://www.postgrowth2018.eu/

[7] https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/en/publikationen/social-well-being-within-planetary-boundaries-the

[8] See APPG ‘Understanding the ‘New Normal’’ briefing paper (part of An Economy That Works series): https://limits2growth.org.uk/publication/aetw_no1/

[9] See APPG ‘Beyond Redistribution’ briefing paper (part of An Economy That Works series): https://limits2growth.org.uk/publication/aetw_no2/

[10] See APPG ‘Wellbeing Matters’ briefing paper (part of An Economy That Works series): https://limits2growth.org.uk/publication/wellbeing-matters-tackling-growth-dependency-briefing-paper/

[11] Corlet Walker, C., Druckman, A. and Jackson, T., 2021. Welfare systems without economic growth: A review of the challenges and next steps for the field. Ecological Economics, 186, p.107066. Available at: https://cusp.ac.uk/themes/aetw/ccw-ad-tj-welfare-postgrowth/

[12] Bailey, D., 2015. The environmental paradox of the welfare state: The dynamics of sustainability. New political economy, 20(6), pp.793-811. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13563467.2015.1079169

[13] Cottam, H. (2018) Radical help: How we can remake the relationships between us and revolutionise the welfare state. London: Virago

[14] See Growing Health Together community hub Twitter page: https://twitter.com/gh_together

[15] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800916303202

[16] Jackson T 2019: “All Models Are Wrong”—The challenge of modelling ‘deep decarbonisation’. CUSP Working Paper No 19. Guildford: University of Surrey. Available at: https://cusp.ac.uk/themes/s2/all-models-are-wrong/

[17] D’Alessandro, S., Cieplinski, A., Distefano, T. and Dittmer, K., 2020. Feasible alternatives to green growth. Nature Sustainability, 3(4), pp.329-335. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-020-0484-y; Keyßer, L.T. and Lenzen, M., 2021. 1.5 C degrowth scenarios suggest the need for new mitigation pathways. Nature communications, 12(1), pp.1-16. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-22884-9

[18] Jackson, T. and Victor, P.A., 2016. Does slow growth lead to rising inequality? Some theoretical reflections and numerical simulations. Ecological Economics, 121, pp.206-219. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0921800915001044

[19] Hausknost, D. (2019) ‘The environmental state and the glass ceiling of transformation’, Environmental Politics. Routledge, 29(1), pp. 17–37. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2019.1680062.

[20] Borowy, I. and Aillon, J. L. (2017) ‘Sustainable health and degrowth: Health, health care and society beyond the growth paradigm’, Social Theory and Health. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 15(3), p. 358. doi: 10.1057/s41285-017-0032-7.

[21] Mazzucato, M. (2018) The value of everything: Making and takingobal economy. London, UK: Allen Lane. p. 208.

[22] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/973285/Inclusive_and_sustainable_economies_-_leaving_no-one_behind.pdf

[23] As distinct from demand driven by increasing desires or preferences for more and better quality goods.

[24] Kingston, A., Comas-Herrera, A. and Jagger, C. (2018) ‘Forecasting the care needs of the older population in England over the next 20 years: estimates from the Population Ageing and Care Simulation (PACSim) modelling study’, The Lancet Public Health. Elsevier Ltd., 3(9), pp. e447–e455. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30118-X.

[25] ONS (2020) ‘Public service productivity: total, UK, 2017’. London, UK: Office for National Statistics, pp. 1–33. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/economicoutputandproductivity/publicservicesproductivity/articles/publicservicesproductivityestimatestotalpublicservices/totaluk2017#adult-social-care.

[26] Authors’ own calculations from Public Health England (2020) ‘Palliative and End of Life Care Profiles’ dataset. Available at: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/end-of-life/data#page/0/gid/1938133060/pat/159/par/K02000001/ati/15/are/E92000001/iid/92489/age/162/sex/4/cid/4/page-options/eng-vo-0_eng-do-0_ovw-do-0 (Accessed: 13 January 2021).

[27] See Age UK’s 2019 report: ‘Age UK General Election Manifesto 2019’. Available at: https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/campaigns/ge-2019/age-uk-general-election-manifesto-2019.pdf

[28] Brand-Correa, L. I. and Steinberger, J. K. (2017) ‘A Framework for Decoupling Human Need Satisfaction From Energy Use’, Ecological Economics. The Authors, 141, pp. 43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.05.019.

[29] Rizan, C., Reed, M. and Bhutta, M.F., 2021. Environmental impact of personal protective equipment distributed for use by health and social care services in England in the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 114(5), pp.250-263. Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/01410768211001583

[30] See for example: Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. In: Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization, Geneva. Available at: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/.

[31] Hilary Cottam finds that social workers spend 80% of their time administering the welfare system, and only 20% with service users. See: Cottam, H. (2018) Radical help: How we can remake the relationships between us and revolutionise the welfare state. London: Virago.

[32] This dynamic is called the cost disease. See William Baumol’s 2012 book ‘The cost disease’ for a full exploration of these issues.

[33] See page 101: of Office for Budget Responsibility (2013) Fiscal sustainability report. London: The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

[34] Christensen, E. W. (2004) ‘Scale and scope economies in nursing homes: A quantile regression approach’, Health Economics, 13(4), pp. 363–377. doi: 10.1002/hec.828.

[35] Corlet Walker C., Druckman A., & Jackson T., (2021). Careless finance: Operational and economic fragility in adult social care. CUSP Working Paper No 26. Guildford: Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity. Available at: https://cusp.ac.uk/themes/aetw/wp26-careless-finance/. See Section 2 for a full exploration of the economic characteristics of adult social care that drive many of the dynamics discussed.

[36] D’Arcy, C. and Davies, G. (2016) ‘Weighing up the wage floor: Employer responses to the National Living Wage’. London, UK: Resolution Foundation, pp. 1–32.

[37] Schmitt, J. (2013) ‘Why Does the Minimum Wage Have No Discernible Effect on Employment?’, Center for Economic and Policy Research, (February), pp. 1–28.

[38] Jackson, T., 2017. Prosperity without growth. UK: Routledge.

[39] Jackson, T. and Victor, P., 2011. Productivity and work in the ‘green economy’: Some theoretical reflections and empirical tests. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1(1), pp.101-108.

Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2210422411000165

[40] http://www.econ.yale.edu/smith/econ116a/keynes1.pdf

[41] Stratford, B. (2020) ‘The Threat of Rent Extraction in a Resource-constrained Future’, Ecological Economics. Elsevier B.V., 169. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106524.

[42] See Section 3 of Corlet Walker et al. (2021) ‘Careless Finance’ working paper (footnote 36) for more information on the use of financial engineering practices in adult social care.

[43] Bed numbers are authors’ own calculations from Care Quality Commission (2021) data. See Corlet Walker et al. (2021) ‘Careless Finance’ working paper (footnote 36) for details of debt-leveraged buyouts in the top 5 care home companies.

[44] Kotecha, V. (2019) ‘Plugging the leaks in the UK care home industry. Strategies for resolving the financial crisis in the residential and nursing home sector’. London, UK: Centre for Health and the Public Interest, pp. 1–53.

[45] Ayash, B. and Rastad, M. (2021) ‘Leveraged buyouts and financial distress’, Finance Research Letters. Elsevier Inc., 38(October 2019), p. 101452. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101452.

[46] See footnote 36

[47] Laing, W. (2008) ‘Calculating a fair market price for care: A toolkit for residential and nursing homes’. Bristol, UK: The Policy Press, pp. 1–56. Available at:

https://www.jrf.org.uk/file/37426/download?token=9UxuQtbA&filetype=full-report

[48] https://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/cresc/research/WDTMG FINAL-01-3-2016.pdf

[49] See Kotecha (2019) ‘Plugging the Leaks’ report, footnote 45.

[50] See reports from the Guardian and the Financial Times, for example: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/apr/30/four-seasons-care-home-operator-on-brink-of-administration; https://www.ft.com/content/0a4d2570-e4f7-11e9-9743-db5a370481bc; https://www.theguardian.com/business/2011/jun/01/rise-and-fall-of-southern-cross

[51] See page 8 of Horton, A. (2020) ‘Liquid home? Financialisation of the built environment in the UK’s “hotel-style” care homes’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, (August), pp. 1–14. doi: 10.1111/tran.12410

[52] https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/childrens-social-care-study

[53] http://www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/portals/0/documents/private%20punishment%20who%20profits.pdf

[54] https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/atg/vol19/iss6/31/

[55] Hausknost, D. (2019) ‘The environmental state and the glass ceiling of transformation’, Environmental Politics. Routledge, 29(1), pp. 17–37. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2019.1680062.

[56] See Stratford 2020, p6 (footnote 42).

[57] Blakeley, G. and Quilter-Pinner, H. (2019) ‘Who Cares? The Financialisation of Adult Social Care’. London, UK: Institute for Public Policy Research, pp. 1–12. Available at: www.ippr.org/research/publications/financialisation-in-social-care.

[58] Authors’ own calculations using the Care Quality Commission’s (2021) care directory data.

[59] Costlow, K. and Parmelee, P.A., 2020. The impact of relocation stress on cognitively impaired and cognitively unimpaired long-term care residents. Aging & mental health, 24(10), pp.1589-1595.

Holder, J.M. and Jolley, D., 2012. Forced relocation between nursing homes: residents’ health outcomes and potential moderators. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 22(4), p.301.

[60] https://www.wired.co.uk/article/care-homes-coronavirus.

[61] See IPPR 2019 report on financialisation in adult social care: www.ippr.org/research/publications/financialisation-in-social-care

[62] Authors’ own calculations using the Care Quality Commission’s (2021) care directory data.

[63] This effect is mitigated by the existence of the Care Quality Commission, who enforces minimum care standards.

[64] Social care is defined as a low-paying industry by the Low Pay Commission. See Skills for Care 2019 report or more detail on sector pay: Dave, G. et al. (2019) ‘The state of the adult social care sector and workforce in England’. Leeds, UK: Skills for Care, pp. 1–124. Available at: www.skillsforcare.org.uk.

[65] See Land for the many report for a discussion of potential property ownership models: https://landforthemany.uk/

[66] For a more in-depth discussion of these options see Australia’s Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (2021): ‘Final Report – List of Recommendations’. Available at: https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/final-report-list-recommendations.

[67] See Kotecha (2019) ‘Plugging the Leaks’ report (footnote 45) for details of debt levels across the adult social care sector.

[68] For a full discussion of this proposal, see: Burns, D. et al. (2016) ‘WHERE DOES THE MONEY GO? Financialised chains and the crisis in residential care Diane’, Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change, (March), pp. 1–68. Available at: http://www.cresc.ac.uk/medialibrary/research/WDTMG FINAL -01-3-2016.pdf.

Download

The full working paper is available for download in pdf (1.7MB). | Corlet Walker C and T Jackson 2021. Tackling growth dependency—the case of adult social care. CUSP Working Paper No 28. Guildford: Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity. A policy briefing was also produced from this work for the UK All-Party Parliamentary Group on Limits to Growth.

Acknowledgements

The financial support of the Economic and Social Research Council for the Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity (ESRC grant no: ES/M010163/1), and of the Laudes Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. Many thanks also to Angela Druckman for her insightful thoughts and comments on the growth dependency framework.