Decolonisation, dependency and disengagement—the challenge of Ireland’s degrowth transition

Advancing degrowth in Ireland requires an understanding of, and a reckoning with, the economic legacy of its colonised past, CUSP researcher Seán Fearon writes. A post-colonial economy within planetary boundaries must break with relationships of dependency and structures of unsustainability.

Blog by Seán Fearon

A few weeks ago, Ireland’s burgeoning degrowth and postgrowth communities gathered to explore the urgent degrowth challenge and take account of the unique contributions from Irish artistry, civic society, and academia that might help to confront it. Billed as the ‘Rethinking Growth’ conference, it brought together leading minds from the international degrowth community in collaboration with scholars, activists and practitioners on the island in what is believed to be the first conference of its kind in Ireland.

It was long overdue, and perhaps marks a watershed for organising degrowth energies and scholarship in a political landscape deprived of radical ecological-economic interventions. These contributions are sorely needed, however. Though small in aggregate terms relative to the larger economies of its neighbours, the post-colonial nature of Irish capitalism and its growth regime has produced an economy whose metabolic and ecological intensity is distinct and disproportionate when compared against other small, open, and high-income economies. To understand why, and to begin to map out a targeted and effective pathway for a degrowth transition, we must understand the structure of the Irish economy as a product of its colonised past.

A potted economic history of colonialism in Ireland

For postgrowth and degrowth economists, the Irish case is both intriguing and urgent. Ireland’s unsustainable FDI-agricultural economy is at once a sordid product of its colonial subjugation, and a source of deep cultural attachment.

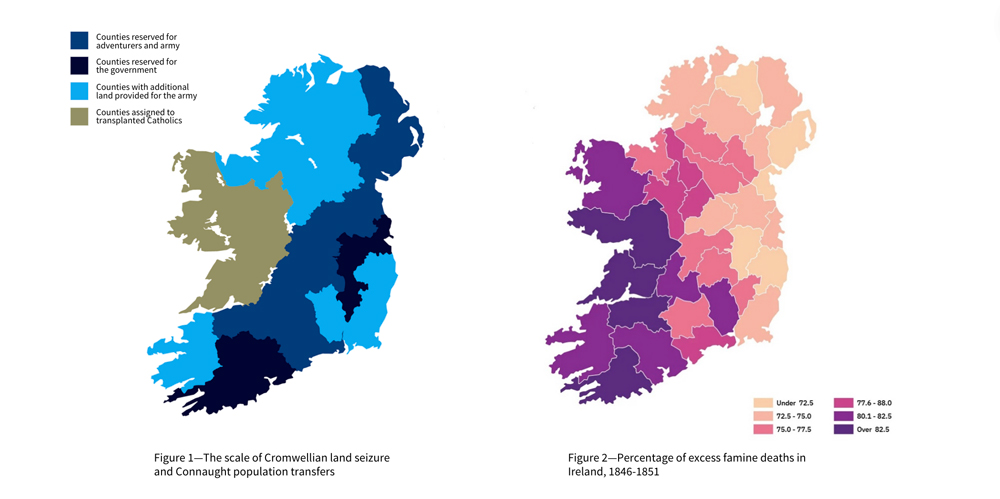

Ireland was among the first colonial experiments on earth, undergoing plantation, pogroms, and population transfers during waves of conquest in the 16th and 17th centuries[1]. Throughout this period, it was also a laboratory for the first conceptions of economic growth and national income. The spoils of Cromwellian land seizures in the 1650s were subject to an innovative quantification by British economist William Petty, whose ‘Down Survey’ meticulously documented the scale and nature of confiscated land to be redistributed to absentee aristocrats and conquering soldiers.

This period created a firm path dependency for Irish economic development, or the lack thereof. Much of the transplanted Irish population were moved to the province of Connaught in the west of the island, where fertile land was scarce and a reliance on the malleable potato crop for subsistence developed. Primitive agriculture would remain the basis of survival for much of the Irish peasantry, as industrial development was systematically undermined by legislative intervention from Westminster to thwart any competition with manufacturing output from the colonial core in England[2]. In short, Ireland would remain a source of agricultural output to suit the requirements of the British colonial project. This process of enforced agricultural stagnation was pithily summarised by Engels (in Slater, 2018, p43)[3]: “Today England needs grain quickly and dependably—Ireland is just perfect for wheat-growing. Tomorrow England needs meat—Ireland is only fit for cattle pastures.”

Exposed by dependency on poor soils and meagre crop yields, particularly in Connaught and Munster, Irish society was decimated by the potato blight and Great Famine of the mid-1840s, a humanitarian catastrophe exacerbated by free market fundamentalists in the British government. The subsequent land clearances, evictions, and pooling of deserted small-hold farms sparked a shift to more intensive and higher value-added forms of animal agriculture on land abandoned by starved or emigrating peasants. Speaking in London in 1867, Marx would famously, and somewhat darkly, summarise this process of depopulation: ‘[o]ver 1,100,000 people have been replaced by 9,600,000 sheep’[4].

Source: Down Survey Project, Trinity College Dublin[5]; RTÉ, 2021[6]

In the absence of any significant and competitive indigenous industrial sectors—and failures to develop them by way of import substitution industrialisation (ISI)—partial independence in the early 20th century would see Irish industrial policy swing heavily to a classic post-colonial strategy. Since the late 1950s[7], Ireland’s growth model has been structured around the attraction of multinational investment, through infamously low corporate taxation, fiscal incentives, and wholesale state policy geared towards the accommodation of FDI flows[8][9]. The extraordinary growth rates of the 1990s, shared with other post-colonial economies in east Asia from whom the ‘Celtic Tiger’ moniker was derived, was a period of unprecedented but belated expansion of wealth in Ireland’s southern state.

Ecological and economic reckoning with post-colonial dependency

This truncated economic history is included here because to face the challenge of degrowth, a departure from this post-colonial legacy of intensive agriculture and multinational-led industrial development is a necessity. Much of the island remains an agricultural economy whose roots run deep in the soils of Irish identity, in the same way British readers in former coal-mining communities might understand. As we have seen, land was historically the basis of social reproduction in Ireland’s peasant past, and therefore often a wellspring of anti-colonial sentiment.

Contemporary Irish agriculture, however, is an industrial affair, where production is directed to huge export markets. As such, it is now a leading cause of biodiversity loss[10], habitat destruction, methane emissions with heightened atmospheric heating effects, and the destruction of Irish waterways such as the ecological disaster at Lough Neagh (the largest freshwater lake in Ireland or Britain, and source of 40% of drinking water in Northern Ireland, whose banks and beds are owned by the current Earl of Shaftsbury by colonial writ). With among the lowest rates of native forest cover and protected land for nature in Europe, much of Ireland’s ‘emerald isle’ is little more than ‘green desert’ in the service of accumulation for industrial agriculture[11].

Irish domestic material consumption (DMC) per capita is consistently among the highest in the EU, due to the material intensity of its export sectors—namely, intensive agriculture—and disproportionately large mining sector (such as huge gypsum mines in south Ulster) (Eurostat, 2023)[12]. The intensity of agricultural production (the sector also producing the highest share of emissions in the Irish state) also means domestic biomass extraction is the highest in the EU (ibid, 2023). Despite modest and insufficient emissions reductions in 2023, Ireland is one of only a few EU countries where emissions are higher than in 1990 and are the third highest per capita in the EU overall.

More significant still is the sheer scale of post-colonial dependency on largely US multinationals for employment, growth, and tax revenues. Despite employing just over a quarter of the total Irish workforce, multinationals resident in Ireland produce almost three quarters of value added (CSO, 2024)[13]. Whilst these firms benefit from a low corporate tax environment, and an unedifying suite of tax loopholes which have earned the Irish economy disrepute as a tax haven, just ten companies pay one in every six euros in tax collected by the Irish state (Cronin, 2023)[14]. In 2022, fully 92% of exports (in monetary value) came from the multinational sector[15], with the largest five firms providing 43% of all exports[16].

This level of fiscal and economic dependence on a handful of booming multinationals is not only irresponsible, but also socially dangerous. Market income inequality in Ireland is among the highest in the OECD (Sweeney, 2023)[17] due in large part to the chasm in productivity between the multinational and indigenous economies. In other words, low-income workers rely heavily on state transfers to meet their basic needs, and these transfers in turn rely heavily on the benevolent presence of companies like Facebook, Apple, and Google. O’Hearn (2001)[18] helpfully summarises the paradox of extraordinary, but poorly distributed, wealth and post-colonial dependency which emerged in Ireland during the late 20th century: ‘Ireland’s long history in the changing Atlantic project was thus subordinate and critical, peripheral and substantial.’

This positioning of the Irish capitalism as a hospitable regime for global tech firms, a site for exports to the rest of the European Union, and as an island retreat from corporate taxation also has serious ecological consequences, on the island and elsewhere in the world. Instructive examples include the data centres required to support the presence of tech companies, which have an extreme, and intensifying, effect on the social metabolism of the island. About one fifth of all electricity consumed in the Republic of Ireland is consumed by data centres—now more than all urban households in the state combined—whose expansion will see this share rise to almost a third by 2030. Somewhat farcically, if all data centres currently proposed were to be constructed, they would consume some 70% of electricity in Ireland’s southern state by 2030 (Irish Times, 2023)[19].

The challenge of disengagement and the opportunities of degrowth

No great elaboration is required as to why this post-colonial model fundamentally incompatible with the essence of the postgrowth project: a good life for all within planetary boundaries. The Irish economy has shattered its ecological limits. Yet inequality is high, and the basic necessities of a dignified life—affordable and low-carbon housing, universal healthcare, public transport, and so on—are denied to communities across Ireland’s northern and southern states. Indeed, to accommodate FDI capital in Ireland, infrastructural development has often prioritised the needs of multinationals to provide the conditions required for growth, over the social requirements of citizens (Bresnihan and Brodie, 2024)[20].

If the metabolic intensity of the Irish economy is to be brought within non-negotiable planetary boundaries, then a new, more secure, sufficient, and socially useful economic model is urgently required. This will require a messy disengagement from unsustainable dependency on flows of foreign capital and their unstable revenues.

This will be messy for a number of reasons. Firstly, weaning from fiscal dependence on multinationals will likely require growth in revenues from less material- and carbon-intensive forms of useful production in the domestic economy, which must be compensated for by degrowth in the multinational sphere. Secondly, though multinational-dominated sectors in Ireland are typically capital-intensive forms of production, their scale has created a structural growth dependency for employment. A degrowth transition requires a shift to labour-intensive production more resistant to ecocidal rates of growth, where labour’s share of income is higher, but which will produce less in the way of surplus to be claimed by an interventionist state. In short, a new model development must pivot towards the indigenous and state sectors as a means of providing essential goods and decommodified, labour-intensive universal services.

In political terms, an embrace of sufficiency, of a minimum living standard as a human right and a maximum level of excess for the rich and super-rich, can force a renewal of, and rediscovery of purpose among, Ireland’s flailing left. The major left formations in Irish politics are unwilling to acknowledge and respect the science of planetary limits because it is difficult and uncomfortable. Indulging in the spurious comforts of green growth allows them to ignore meaningful politics of redistribution, and the onerous task of carving out a political space for radical socioeconomic change. In some corners, even acknowledging net zero as a viable objective is proving a difficult task.

Moreover, Ireland now faces a groundswell in far-right sentiment and agitation, in urban and rural communities. Thus far, the responses from Ireland’s political mainstream have been to reject the messengers of fear and division, but chase after the festering effects of their message. An uncompromising politics of meeting the basic needs for all, by unapologetic means of redistribution and intervention, is the only antidote to this far right poison. Perhaps we can all take hope from the French left in this regard.

The degrowth challenge is a structural one, requiring transformational change of the post-colonial model of Irish capitalism, and a radical politics inside and outside of elected institutions to advocate for this transformation. The seeds of this project in Irish academia may have been sown at ‘Rethinking Growth’, the largest and most significant gathering of postgrowth and degrowth activists and scholars yet assembled in Ireland.

Link

For further details about the ‘Rethinking Growth’ conference (25-26 June 2024), please see: https://rethinking-growth.ie.

Notes

[1] McVeigh, R & Rolston, B 2021, Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution. Beyond the Pale Publications, United Kingdom.

[2] McCann, G., 2011. Ireland’s Economic History: Crisis and Development in the North and South. London: Pluto Press

[3] Slater, E., 2018. Engels on Ireland’s Dialectics of Nature. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 29(4), pp. 31-50.

[4] Marx, K. & Engels, F., 1971. Ireland and the Irish Question. Moscow: Progress Publishers Moscow.

[5] https://downsurvey.tchpc.tcd.ie/history.html

[6] https://www.rte.ie/history/post-famine/2021/0324/1205908-the-effects-of-the-great-famine-explore-the-maps/

[7] Government of Ireland, 1958. Programme for Economic Expansion, Dublin: Programme for Economic Expansion

[8] Kirby, P., 2010. Celtic Tiger in Collapse: Explaining the Weaknesses of the Irish Model. 2 ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan London

[9] In many cases, this submission of state policy to the interests of international capital resident in Ireland have resulted in ambivalence towards ecological degradation (Bresnihan and Brodie, 2024)

[10] https://biodiversityireland.ie/ipbes-irelands-biodiversity-crisis/

[11] https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/2023/09/07/ireland-needs-more-wild-native-forests-not-lifeless-sitka-plantations/

[12] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/env_ac_mfa__custom_12173583/default/table?lang=en

[13] https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-biidr/businessinireland2021detailedresults/multinationalsanirishperspective/

[14] https://www.fiscalcouncil.ie/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Understanding-Irelands-Top-Corporation-Taxpayers-Brian-Cronin-Fiscal-Council-2023.pdf

[15] https://enterprise.gov.ie/en/publications/publication-files/annual-business-survey-of-economic-impact-2022.pdf

[16] https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-ti/irelandstradeingoods2022/concentrationofvalueoftraders2022/

[17] https://www.tasc.ie/assets/files/pdf/the_state_we_are_in_2023.pdf

[18] O’Hearn, D., 2001. The Atlantic economy: Britain, the US and Ireland. Manchester/New York: Manchester University Press.

[19] https://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/data-centres-could-use-70-of-ireland-s-electricity-by-2030-committee-to-hear-1.4685589

[20] Bresnihan and Brodie, 2024, ‘From toxic industries to green extractivism: rural environmental struggles, multinational corporations and Ireland’s postcolonial ecological regime’, Irish Studies Review