Living well today and tomorrow: young people, good life narratives, and sustainability

Anastasia Loukianov, Kate Burningham and Tim Jackson

CUSP Working Paper Series | No 39

Summary

In this working paper, we explore young people’s use of shared social understandings to describe what is important in their present lives, to envision their futures, and to respond to the challenges they identify to the realisation of their good lives. Understanding ‘good lives’ as a socially constructed concept, we focus on young people’s discourses given the role of discourse in bringing realities about and shape what is thought about and how. We use data generated from focus groups carried out in the context of a filmmaking project that took place in 2018-2019 with young people aged 10-14 living in Surrey (South-East England). In this project, four groups of 4-8 young people (n = 22 total) from diverse socio-economic backgrounds shared their views on what living well meant to them. We focus on the different good life narratives that young people used to describe what living well means in their present and future lives, as well as how they talked about navigating the future. We show that young people both used narratives which contested the consumerist understanding of living well and used narratives which reproduced the status quo. Highlighting the relationship between sustainability and deliberative democracy, we conclude by emphasising the necessity to listen to young people even when their understandings contradict scholarly definitions of wellbeing and sustainability.

Introduction.

In this working paper, we explore young people’s use of shared social understandings to describe what is important in their present lives, to envision their futures, and to respond to the challenges they identify to the realisation of their good lives. As Burningham and Venn (2022: 79) explain, ‘sustainability is increasingly understood as the capability to live well or achieve a “good life” within environmental limits.’ While there are definite aspects that are necessary to live well, such as sufficient nutritional intake and shelter, the meaning of a ‘good life’ is also socially constructed (Dean, 2003). Hence social understandings of what living well means are extremely important to any attempt at enabling sustainable living. Young people’s processes of meaning-making are supported by the shared narratives of the good life which are available in their particular sociocultural and historical contexts. These social narratives vary across space and time and constitute constantly evolving resources for making sense of the good life (McMahon, 2006). They give directives regarding how one should strive to live. Indeed, the stories humans tell, the concepts they use, and the metaphors they live by have been shown to shape their behaviour (Lakoff & Johnson, 2003), playing a crucial, but not determining, role in how people lead their lives. Discourses do not merely describe existing realities but help bring them into being and shape what is thought about and how it is thought about (Hajer & Versteeg, 2005).

Recently, a range of studies taking a broad focus on discourses have been carried out in relation to children’s and young people’s understandings of wellbeing. Existing research highlights the role played by discursive repertoires in enabling particular understandings (Savahl et al., 2015), the importance of context in making repertoires available (O’Flynn & Bendix Petersen, 2007), and the struggles that disadvantaged groups may experience in establishing their understandings (Loera-Gonzalez, 2014). Contemporary research has seen an increasing push to seek out children’s and young people’s own definitions of wellbeing (Redmond et al., 2016). This strand of research is still at a relatively early stage and much remains to be explored. With notable exceptions (e.g. the Children and Youth in Cities: Lifestyle Evaluations and Sustainability – CYCLES project), research on young people’s understandings of their good lives pays limited attention to environmental sustainability, especially in studies focusing on the highly environmentally impactful European, North American, and Australasian societies (e.g. Ben-Arieh et al., 2014; Bradshaw, 2016; The Children’s Society, 2021).

Yet, social understandings of living well are tied to questions of environmental impacts and social justice, as each ‘good life’ implicitly entails different levels of material throughput. In the contemporary societies of Europe, North America, and Australasia, the consumerist understanding of the good life dominates (Jackson, 2017), and an increasing number of social and cultural functions are carried out and satisfied through the consumption of commodities (Evans & Jackson, 2008). As this understanding of living well is increasingly evidenced to be linked with high-environmental impacts, unstable economies, and social injustice (Jackson, 2017), the need for new stories of what living well means that can support just, economically stable, and ecologically sustainable societies is heightened (Jackson, 2017). In this context, young people are sometimes unproblematically framed as ‘agents of change’ who naturally contest established understandings, create their own subversive meanings (Miles, 2015), and become bearers of hope for delivering sustainable futures (Walker, 2017).

Drawing from a filmmaking research project with young people aged 10-14, we focus on the different good life narratives that young people used to describe what living well means in their present and future lives, as well as how they talked about navigating the future. We show that young people both used narratives which contested the consumerist understanding of living well and used narratives which reproduced the status quo. We conclude by highlighting the relationship between sustainability and deliberative democracy.

The Study.

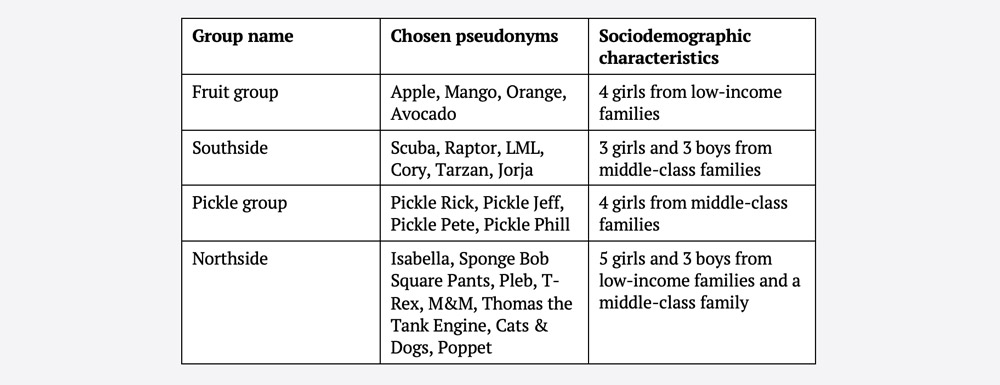

The insights presented in this working paper stem from a filmmaking project carried out in 2018-2019 with young people aged 10-14 living in Surrey (South-East England). Surrey is a predominantly White British, highly educated, and economically prosperous region. Yet, despite its reputation of affluence, according to the 2019 Index of Income Deprivation Affecting Children, many Surrey towns display strong disparities between their localities. Four groups of 4-8 young people (n = 22 total) were recruited from a local secondary school, a youth club, and through snowball sampling starting from the authors’ contacts. The young people who took part in the project came both from economically disadvantaged and relatively well-off backgrounds. Most participants were White British, but a few young people were from Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic groups. A summary of sociodemographic characteristics and pseudonyms chosen by the participating young people is presented below (Table 1).

Table 1: Table of attributed group names, chosen pseudonyms, and sociodemographic characteristics

Young people were invited to participate in three research activities: an initial audio-recorded focus group on their understandings of living well, a filmmaking task on wellbeing, and an audio-recorded reflexive screening session. The initial focus groups asked young people about topics such as their understandings of the meaning of living well, their daily routines, and their hopes and aspirations for the future. Young people were then introduced to filming and provided with simple point-and-shoot cameras. Films were created alone or in small groups of two or three. Young people filmed in their free time and during research sessions. Editing was carried out exclusively during research sessions with the support of Anastasia and research facilitators when they were present. When finished, the films were screened in each group to give young people an opportunity to reflect and elaborate on the finished products. The audio-recordings were transcribed, and both transcripts and films were analysed thematically. Prior to being carried out, the study underwent ethical review and received a favourable ethical opinion from the University of Surrey ethics committee.

Throughout this working paper, we focus on the shared social understandings that are used by young people. Rather than attempting to evaluate the sustainability of our participants’ lifestyles, our aim is to show the complexity and diversity of young people’s use of social understandings of living well.

Good life narratives, sustainable living, and discourses to navigate the future.

The insights presented in this working paper stem from a filmmaking project carried out in 2018-2019 with young people aged 10-14 living in Surrey (South-East England). Surrey is a predominantly White British, highly educated, and economically prosperous region. Despite its reputation of affluence, according to the 2019 Index of Income Deprivation Affecting Children many Surrey towns display strong disparities between their localities. Four groups of 4-8 young people (n = 22 total) were recruited from a local secondary school, a youth club, and through snowball sampling starting from the authors’ contacts. The young people who took part in the project came both from economically disadvantaged and relatively well-off backgrounds. Most participants were White British, but a few young people were from Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic groups. A summary of sociodemographic characteristics and pseudonyms chosen by the participating young people is presented below (table 1).

We begin by introducing the good life narratives that young people used to describe what living well meant to them, before explaining how narrative use varied depending on the topic of conversation. Then, we provide an example of how good lives could be realised in practice before ending on a discussion of young people’s responses to the challenges they identified to the realisation of their good lives.

Three narratives of the good life.

We identified three types of narratives: lavish dreams, the ‘good enough’ life, and the ‘caring’ life which implicitly entail different levels of material throughput. In nearly all groups, at least one person used the narrative of lavish dreams to describe the meaning of living well. This narrative relates to the traditional consumer dream, in which a good life is one that abounds in material comforts, luxury goods, and status acquired through material and financial wealth. For instance, LML explained:

‘[…] my ideal type of life is a big mansion and playing basketball every day. Netflix… to be a basketball player, an actor, or a musician, and to be really famous.’

Similarly, Pickle Pete said that she wanted to become a ‘trillionaire’, Pleb specified that she wanted to make a lot of money and buy a big house in which she would live with all her friends, and all three boys from Southside had a particular interest in luxury cars. Participants also recurrently said that others in their schools wanted to become wealthy. This narrative was seldom used in reference to young people’s current lives and rather referred to dreams for their futures or alternative ideals that they knew were likely unattainable.

Nonetheless, most young people rejected this narrative of the good life and lavish dreams fell under strong criticisms. Referring to the mainstream consumer dream as the ‘perfect life’ or the ‘really good life’, all the participants from the Fruit group strongly spoke out against it. For them, these types of lives would be ‘boring’. Additionally, they explained that in their school, living the consumer dream could warrant negative judgement from peers. Instead, the girls from the Fruit group, as well as a few participants from other groups, talked about just wanting a ‘normal life’. For Avocado, the ideal type of live would be:

‘decent friends, decent family, decent job […] not being like, if someone said “oh do you want to go out for dinner?” and you’d be like “no it’s alright I can’t”. I want to be like, “yeah sure, let’s go.”’

Similarly, Jorja’s normal life involved a secure living environment, a family, and friends. The good enough approach to living well seemed to make appeals to the experiential rather than material aspects of life and emphasised connections with significant others:

‘I think it’s not all about houses but more about the neighbourhood and the area. Cause like what I like about where we live at the moment is that we have so many friends living near us so we can just knock on their door and just go’ (Jorja)

Yet, in practice, what ‘good enough’ meant and the amount of material and financial resources that were needed to sustain a ‘normal’ life varied between participants and between groups. For instance, Orange and Avocado explained that to them, the good enough life involved shopping for clothes at least once a week, as opposed to everyday in the lavish dreams life. Hence the meaning of sufficiency is flexible, and in consumer societies it is likely to gradually require increasing consumption. Indeed, Walker et al. (2016) explain that culturally embedded understandings of need have changed over time, as people perceive an increasing array of goods as basic necessities.

The narrative of caring life emphasised spending time with significant others, and stressed experiential aspects of wellbeing, which resonated with the previous narrative. But while it regrouped multiple elements from the good enoughlife, it also made a point to take into account the influence of one’s lifestyle on others and emphasised the reliance of humans on their environment. This narrative also entailed both taking into consideration the influence of one’s good life on the capacity of one’s contemporaries to pursue a good life, but also on the capacity of future people:

‘I mean if people keep… people who are doing the deforestation and killing the wild and things, they are not really thinking about the future like because in the future… we are ruining the world for future people. It’s not their fault, they haven’t done anything, and their world is gonna be horrible if we don’t do anything.’ (Scuba)

In that sense, this approach could be likened to the discourse of sustainable development, notably as established by the report produced by the Brundtland commission in 1987. It is also in line with Plumwood’s (2008) relational framework which outlines the requirement to care for ‘shadow places’, namely, the places of support that enable one to have the good life that one does. This approach was less popular than that of the good enough life, but it could be encountered in the discourses of a few young people, notably in relation to discussions about nature, animals, or the environment. It is notable that contrary to lavish dreams, the narrative of the good enough and that of the caring life were employed to describe both present realities and hoped for futures.

Different narratives for different agendas.

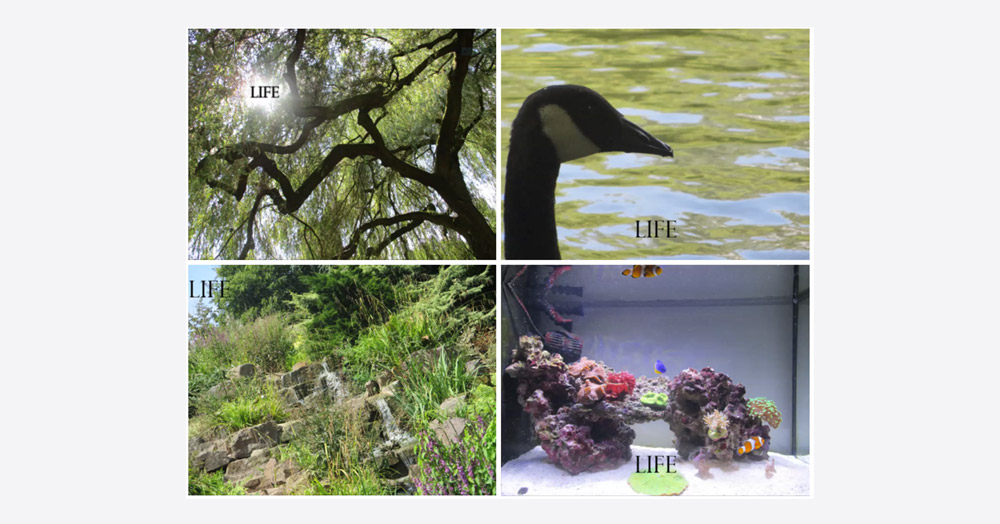

It is striking that young people did not use a single narrative throughout, and rather alternated between narratives depending on the topic they were discussing. For instance, to create his film, Cory used still images which he classified into various categories. One of those categories was ‘Life’, which included images of trees, a goose, a waterfall, and aquarium fish (Figure 1). When asked to explain what he meant by ‘Life’, Cory said: ‘Life like, the living world and things… the people in this room…’, placing different forms of life on equal footing. Hence, in relation to the environment, Cory used the narrative of caring life. Conversely, when discussing cars, Cory employed the narrative of lavish dreams, naturally changing linguistic repertoires as he changed conversation topics.

Figure 1: Stills from Cory’s film about the meaning of the good life.

Cory was not the only one who alternated between narratives. Similarly, Pickle Pete both used the narrative of lavish dreams in relation to her ideal life and the narrative of caring life when explaining the importance of the environment to human life. This readily resonates with earlier work on discourses, such as that of Wetherell and Potter (1988: 171) who explained that ‘speakers give shifting, inconsistent and varied pictures of their social worlds’. The authors argued that most commonly, people simply did what came naturally to them and responded to the demands of the situation, rather than giving straightforward reflections of their mental states or attitudes.

The co-existence of multiple good life narratives may provide an explanation for perception of a ‘value-action’ gap in young people’s relationship to the environment (Stanes et al., 2015). For instance, in the Pickle group, the participants agreed that environmental impact was an issue of concern and were opposed to harsh treatment of animals. But they also found pleasure in the taste of meat and struggled to conciliate these different understandings:

Pickle Jeff: Well I don’t like the thought of animals being kept harshly.

Pickle Rick: Or being killed.

Pickle Jeff: Or being killed!

Pickle Pete: Or small cages.

Pickle Jeff: Yeah, they do suffer from worrying so that plays a big part in it. But I like the taste of meat.

This is consistent with existing research suggesting that awareness of environmental or social consequences does not necessarily translate into the uptake of less environmentally impactful or fairer practices (Autio & Heinonen, 2004). Indeed, in a study of Finnish young people’s consumption practices, Autio and Heinonen (2004) argued that their participants were simultaneously materialistic and environmentally concerned.

Additionally, for Ojala, (2008), young people’s environmental ideals can be difficult to realise in the context of their everyday lives. As adults, young people navigate their everyday lives responding to the demands of a multiplicity of conflicting agendas rather than following a single, consistent life project (Evans & Abrahamse, 2009). Most young people who took part in the project were aware of environmental impact and actively took steps to reduce their personal environmental footprint, such as recycling or switching off taps. In fact, other kinds of actions can be difficult to take for young people due to their structural position (Walker, 2017) and to the normative and infrastructural constraints that consumer societies put on such actions.

Realising good lives in consumer societies: the example of sociality.

While young people use good life narratives inconsistently, social norms and structures can favour the realisation of particular understandings of what living well means over others. In the case of dominant social narratives, expectations of a good life are supported by technologies, institutions, and practices which facilitate the realisation of such good lives. In consumer societies, the ability to take part in regular shopping trips is expected as part of a ‘good enough’ or ‘normal’ life, as participants explained. As items and practices become normalised and perceived as necessities, living without them becomes increasingly difficult. Townsend (1979: 31) observed that destitution is not merely a matter of imperilled subsistence, but one of exclusion from ‘ordinary patterns, customs, and activities.’ As Jackson (2006) explains, in consumer societies a growing number of social and cultural functions are performed through acts of consumption, making it paramount to many young people’s lives.

Indeed, for many of the girls who took part in the project, shopping for clothes was understood as a leisure activity. It was talked about with enthusiasm in every group except Northside, where it was not mentioned at all[1]. In addition to browsing and purchasing clothing, shopping trips also often involved going to fast food outlets or coffee shops. However, going shopping was, as participants pointed out, not necessarily motivated by a desire to buy something but understood as a social activity to be carried out with friends. Nonetheless, it required being able to buy potential goods as participants only went shopping when they had money to spend, and the outing often resulted in a purchase:

‘Sometimes I’m like ok I won’t buy anything and then I’m like, I’ve bought stuff, sorry!’ (Apple)

‘Every time I go into town, I always end up buying something to do with food.’ (Jorja)

Shopping outlets were not the only means for realising sociality. In all groups, regardless of gender or socioeconomic background, young people extensively talked about spending time in parks and on social media. Parks were valued because they were both a place where young people could hang out independently of adult supervision. Young people enjoyed parks for the facilities that they offered (i.e. swings) and for the opportunity that they gave them to spend time together. In fact, participants explained that they rarely ever went to parks on their own. The importance of places of independence to young people has been noted in relation to spaces such as disused urban green areas (Hallam et al., 2019), and can be extended to parks. But depending on the area that one lived in, adequate green space could be difficult to come by. Poppet, who was initially quiet and difficult to engage, sprung up when asked what could be made better in her neighbourhood:

‘Have a garden for flats. They said they would have that done, and they still haven’t. It’s been two years now! Where I live there is that car park and like with many flats, and there is basically nothing there. There is no park, nowhere to go, or anything’.

Pickle Pete, who lived in a small village, also talked about the lack of parks for young people to spend time in. Additionally, young people in Northside reported more concerns with safety in parks than young people in other groups, further complicating access to these spaces for them. Social media on the other hand provided a space of relative autonomy and independence that all participants could access. Parks, shopping outlets, and social media provide spaces where young people can meet each other, develop relationships, and spend time with friends and significant others, which were important to their good lives. In this case, it seems that these three spaces fulfil similar ends – enabling young people to socialise. But some spaces are more easily accessible for young people or more strongly favoured by social norms and structures. Dobson et al. (2019) note a disinvestment over the past decade in public green space, including neighbourhood parks and playgrounds in the UK. As local green space is maintained by local governments, this disinvestment is particularly salient in economically disadvantaged localities who have been especially impacted by cuts to local authority funding (Lewer & Bibby, 2021). Additionally, teenagers are not always welcome in parks, drawing suspicion from parents and neighbours (Owens, 2018). Young people from Northside talked about their experiences of being chased away from parks by the police or by other adults.

Conversely, at least for young women, shopping trips seem to be framed as a rite of passage to independence (Russel & Tyler, 2005; Cody, 2012). As Pickle Pete explained:

‘I like shopping because I get away from my parents ‘cause they don’t usually come with me. And then… it’s not just to get away from them but like it feels like… alone and grown up. I can get my own stuff, you know what I mean?’

Going shopping, disposing of one’s own money, and making consumption choices were understood as signs of maturity. Young people recognised this and knew that being unable to take part put them at a disadvantage in relation to their peers. For instance, Pickle Jeff, who was the only one from her group who had not yet been on a shopping trip with friends gave extensive and thorough justifications as to why such a trip had not yet materialised. Hence some of the projects which are of importance to young people, such as socialising, being accepted, and coming of age are intertwined with consumer pursuits. As Miles argues (2015), if consumption is the primary means of realising a range of social and cultural functions in consumer societies, as adults, young people are more likely to reproduce dominant understandings than to challenge them.

Navigating the future: technological innovations, social change, and nihilism.

Throughout the project, young people manifested an awareness of the social, economic, and environmental conditions which may make it difficult for them to achieve the lives they were hoping for. For instance, young people in Southside were concerned about the potential impact of Brexit, young people in Northside extensively talked about Donald Trump, and all groups discussed their concerns in relation to environmental issues such as climate change, pollution, and local problems (e.g. lack of adequate green space in Northside). In this section, we present three discourses that young people used to respond to these challenges: technological innovation, social change, and nihilism.

While ultimately the amount of data available in relation to young people’s attribution of responsibility for positive action was limited, in many groups social and environmental issues were naturally brought up by young people when talking about their desired futures and plans for realising them. It was in Southside that young people most explicitly took different approaches to environmental issues. For some of the participants, technological innovations were expected to provide adequate solutions to environmental issues. For instance, LML argued that significant improvements were already underway:

‘It’s getting better though. They are designing electric cars and stuff, and they are going to become cheaper and then… we can ride them and stuff.’

The technological innovations discourse placed responsibility on experts, technological innovators and entrepreneurs to deliver positive action. The appeal to technological innovations resonates with the ecological modernisation discourse which acknowledges ‘design faults’ but does not promote doing away with the institutions of modern production and consumption (Carolan, 2004). It is a popular approach which has been favoured within consumer societies and it is unsurprising that environmental progress was sometimes framed in this way.

Conversely, a few young people used a discourse which promoted social change and highlighted their own agency and responsibility to play a part in such change. This kind of discourse was used in relation to a variety of topics. Scuba highlighted the moral responsibility humans had to act on environmental breakdown, while Isabella, a visually impaired young person, talked about social discriminations:

‘I think like for me, I’m not very popular and I don’t have many friends at school because I walk with a walking aid and maybe because I look different… […] Like if they spoke to me, like they might like or not like me, but they just don’t talk to me. Like… would you like it if no one spoke to you cause you look different? Or you have something a bit different?’

For these reasons, she wanted to ‘make the world a better place’ and was prepared to take action to his effect:

‘I feel like you can change society by writing or politics, but like I definitively want to change the world.’

Scuba and Isabella actively framed themselves as agents of change and laid out possible routes for enacting such change, but this was not the case for all young people.

In the discussions that we had with the Northside and the Pickle groups, young people used a discourse less explicitly related to responsibility for positive action, but which permeated our discussions. Young people recurrently described themselves and others of their acquaintance as persons who do not engage in many activities and do not spend time with others. Young people qualified this type of person as being ‘antisocial’. For instance, Pleb explained that on an ordinary day, her activities were to ‘Play Xbox and be antisocial!’. The meaning of ‘antisocial’ here differs from that which typically appears in psychological research. For the young people who took part in this project, being antisocial meant ‘seeing no one’ (Pleb) and ‘just staying at home’ (T-rex). Describing oneself in this way did not necessarily preclude taking part in a range of social activities. Sponge Bob Square Pants for instance used the term to refer to himself, and later talked with enthusiasm about having a part in a theatre play and being a member of a music band.

Originally a pejorative term, here ‘antisocial’ seemed to be used in a relatively favourable way, perhaps as a means of defying social expectations of sociality and asserting one’s right to do as one pleases. In the Pickle group the term was explicitly articulated against the neoliberal productive self. When asked about their hobbies, the Pickle girls said:

Pickle Jeff: I do gymnastics, swimming. Sometimes I play football.

Pickle Pete: I do hockey, I walk a dog for about an hour and get a fiver for it! And then what else do I do…? I do horse riding, and I do gymnastics, and piano and drums.

Pickle Phil: My talent is moving my fingers really fast like that.

Pickle Rick: My skill is being antisocial.

Pickle Phil: Same.

Pickle Rick and Pickle Phil used ways to present themselves that were drastically different from those used by Pickle Jeff and Pickle Pete. While Pickle Jeff and Pickle Pete provided long lists of their hobbies, Pickle Phil and Pickle Rick refused to conform to these expectations. In this way, they may either be rejecting the neoliberal imperative of ‘being busy’ (O’Flynn & Bendix Petersen, 2007: 463) or they may be making an ironic reflection on others’ opinions of their occupations. Either way, being ‘antisocial’ was not limited to simply avoiding social interaction. Instead, it seemed to be extended to encompass a rejection or suspicion of traditional meanings, taking nihilistic undertones.

Young people who referred to themselves as antisocial also tended to feel disempowered in the face of global challenges and sometimes made appeal to superhuman forces to take action:

‘I had a dream once that if I had superpowers I’d be Flash and pick up all the litter.’ (Pickle Rick)

Similarly, Thomas the Tank Engine wished he could solve world issues by raising an animal army and enacting world domination. Both dreamed of being able to make a difference but suggested that the impact that humans could have was limited. Hence, far from automatically framing themselves as agents of change, young people used a variety of approaches to broach the future and attribute responsibility for positive action. Discourses which contested established norms and understandings sometimes validated the expectation that young people should be leading figures in sustainability transitions (Miles, 2015; Walker, 2017). Other times, divergent discourses did not easily align with these expectations.

Conclusion.

In their day-to-day experiences, young people engage with a range of different discourses. Using the good life narratives of lavish dreams, good enough life, and caring life, young people alternated between narratives in different contexts. As adults, they have to negotiate a range of contradictory understandings of what living well means which implicitly entail different levels of material throughput. Additionally, the social norms and structures of consumer societies tend to encourage the realisation of good lives via the purchase of consumer goods (e.g. sociality via shopping) or in ways that do not contradict the consumerist framework (e.g. environmental action via recycling).

Nonetheless, young people often resisted explicitly consumerist understandings of living well. But the rejection of traditional meanings does not always take the shape expected by youth and environmental researchers, complicating the relationship between young people’s concern for the environment and the framing of youth as agents of change. While many young people were environmentally concerned, this did not necessarily lead them to framing themselves as agents of change, or exclusively using the narrative of caring life. Instead, environmental stewardship took a variety of forms in young people’s lives. While some young people, such as Scuba, highlighted their own responsibility to act, others more readily called for technological innovations, and in many cases young people rather explained their inability to effect change and revendicated their right to focus on their own lives.

As we suggested earlier, use of discourse does not straightforwardly reflect mental states or attitudes, but paying attention to them is important because different discourses:

‘[…] effectively offer different versions of ‘‘common sense’’. That is, they are not just different ways of talking, but different ways of making judgements and dealing with new information—deciding what things really mean, what is right and what is wrong, what is acceptable and unacceptable, what flows logically from what’. (Ereaut & Whiting, 2008: 10)

Some of the understandings which could support living well within planetary limits, such as the narrative of caring life, already exist and are regularly used by young people in contexts relating to nature and animals. Additionally, there is evidence of the variability of the material intensity of good enough lives. But there is a need for social structures and physical infrastructures which support their realisation of good lives more sustainably and facilitate young people living out their environmental ideals. In this regard, governments and corporations have an important role to play in enabling the transition to more sustainable ways of living.

But the use of narratives which are ‘seemingly counter to established approaches to sustainability and […] wellbeing’ is no less valid and no less worthy of attention and recognition, as Burningham and Venn (2022: 91) explain. Sustainability cannot be achieved merely through specific technological and infrastructural changes, or through the cementing of a new ‘sustainable’ good life narrative which privileges the perspectives of one group over another (Hammond, 2019). Hence, Hammond explains, sustainability must be understood as an ongoing process which involves genuine inclusive decision-making and allows for the serious consideration and realisation of a multiplicity of understandings of living well. This cannot happen without careful and sustained attention to young people’s perspectives on what makes a good life, regardless of whether or not they align with scholarly perspectives on sustainability (Burningham & Venn, 2022).

Notes

[1] It is unclear whether these themes were simply never brought up, or whether this was linked to economic disadvantage and distance from shopping outlets.

References

Autio, M./Heinonen, V. (2004): To consume or not to consume? Young people’s environmentalism in the affluent Finnish society, in: Young, volume 12, vol.2, pp. 137-153

Ben-Arieh, A. et al (2014): Multifaceted concept of child well-being, in: Ben-Arieh, A. et al.: Handbook of Child Well-Being. Theories, Methods, and Policies in Global Perspective, Drodrecht: Springer

Burningham, K./Venn, S. (2022): “Two quid, chicken and chips, done”: understanding what makes for young people’s sense of living well in the city through the lens of fast food consumption, in: Local Environment. The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, volume 27, vol.1, pp. 80-96

Bradshaw, J. (2016): The Wellbeing of Children in the UK. Bristol: Policy Press

Carolan, M.S. (2004): Ecological modernisation theory: what about consumption?, in: Society & Natural Resources. An International Journal, volume 17, vol.3, pp. 247-260

Cody, K. (2012): “No longer, but not yet’’: Tweens and the mediating of threshold selves through liminal consumption, in: Journal of Consumer Culture, volume 12, vol.1: pp. 41-65

Dean, H. (2003): Discursive Repertoires and the Negotiation of Well-Being: Reflections on the WeD Frameworks. WeD Working Paper 4. ESRC Research Group on Wellbeing in Developing Countries, London: London School of Economics.

Dobson, J. et al. (2019): Space to thrive. A rapid evidence review of the benefits of parks and green spaces for people and communities. London: The National Lottery Heritage Fund and The National Lottery Community Fund

Evans, D./Abrahamse, W. (2009): Beyond rhetoric: the possibilities of and for ‘‘sustainable lifestyles’’, in: Environmental Politics, volume 18, vol.4, pp. 486-502

Evans, D./Jackson, T. (2008): Sustainable consumption: perspectives from social and cultural theory. RESOLVE working paper 05-08. Online access [12/06/18]: http://resolve.sustainablelifestyles.ac.uk/sites/default/files/RESOLVE_WP_05-08.pdf/

Ereaut, G./Whiting, R. (2008): What do we mean by «Wellbeing»? And why might it matter? London: Department for Schools and Families. Online access [12/06/19]: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/8572/1/dcsf-rw073%20v2.pdf/

Gottweis, H. (2003): Theoretical strategies of poststructuralist policy analysis: towards an analytics of government, in: Hajer, M./Wagenaar, H., Deliberative policy analysis: Understanding governance in the network society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Hajer, M./Versteeg, W. (2005): A decade of discourse analysis of environmental politics: Achievements, challenges, perspectives, in: Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, volume 7, vol. 3, pp. 175-184

Hammond, M. (2019): A cultural account of Ecological Democracy, in: Environmental Values, volume 28, vol. 1, pp. 55-74

Jackson, T. (2017): Prosperity without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow, London: Routledge

Jackson, T. (2006): Consuming Paradise? Towards a social and cultural psychology of sustainable consumption, in: Jackson, T., Earthscan Reader in Sustainable Consumption. London: Earthscan.

Lakoff, G./Johnson, M. (2003): Metaphors We Live By, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lewer, D./Bibby, J. (2021): Cuts to local government funding and stalling life expectancy, in: The Lancet Public Health, volume 6, vol. 9, E623-E624

Loera-Gonzalez, J. (2015): Authorised voices in the construction of wellbeing discourses: a reflective ethnographic experience in Northern Mexico, in: White, S./Blackmore, C., Cultures of Wellbeing. Method, Place, Policy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

McMahon, D.M. (2006): The Pursuit of Happiness: A History from the Greeks to the Present. London: Penguin Books.

Miles, S. (2015): Young people, consumer citizenship and protest: the problem with romanticising the relationship to social change, in: Young, volume 23, vol. 2, pp. 101-115

O’Flynn, G./Bendix Petersen, E. (2007): The ‘’good life’’ and the ‘’rich portfolio’’: young women, schooling and neoliberal subjectification, in: British Journal of Sociology of Education, volume 28, vol. 4, pp. 459-472.

Ojala, M., (2008): Recycling and ambivalence: Quantitative and qualitative analyses of household recycling among young adults, in: Environment and Behavior, volume 40, vol. 6, pp. 777-797.

Owens, P.E. (2018): “We just want to play”: Adolescents speak about their access to public parks, in: Children, Youth and Environment, volume 28, vol. 2, pp. 146-158

Plumwood, V. (2008): Shadow places and the politics of dwelling, in: Australian Humanities Review, volume 44, pp. 139-150

Redmond, G., et al. (2016): Are the kids alright? Young Australians in their middle years. Final report of the Australian Child Wellbeing Project, Flinders University, University of New South Wales, and Australian Council for Educational Research.

Russel, R./Tyler, M. (2005): Branding and bricolage. Gender, consumption, and transition, in: Childhood, volume 12, vol.2, pp. 221-237

Savahl, S. et al. (2015): Discourses on well-being, in: Child Indicators Research, volume 8, vol. 4, pp. 747-766

Stanes, E./Klocker, N./Gibson, C. (2015): Young adult households and domestic sustainabilities, in: Geoforum, volume 65, pp. 46-58.

The Children’s Society (2021): The Good Childhood Report 2021. London: The Children’s Society.

Townsend, P. (1979): Poverty in the United Kingdom, London: Penguin Books.

Walker, C. (2017): Tomorrow’s leaders and today’s agents of change? Children, Sustainability Education and Environmental Governance, in: Children & Society, volume 31, vol. 1, pp. 72-83

Walker, G./Simcock, N./Day, R. (2016): Necessary energy uses and a minimum standard of living in the United Kingdom: energy justice or escalating expectations?, in: Energy Research & Social Science, volume 18, pp. 129-138

Wetherell, M./Potter, J. (1988): Discourse analysis and the identification of interpretative repertoires, in: Antaki, C., Analysing Everyday Explanation. A Casebook of Methods. London: Sage Publications

The full paper is available for download in pdf (5MB). | Loukianov A, Burningham K and T Jackson 2024. Living well today and tomorrow: young people, good life narratives, and sustainability. CUSP Working Paper No. 39. Guildford: Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity.

Acknowledgements

This working paper has been published in German as ‘Heute und Morgen Gut Leben: Junge Menschen, Erzählung von gutem Leben un von Nachhaltigkeit’ (2024) in Braches-Chyrek, R.; Röhner, C.; Moran-Ellis, J.; and Sünker, H. (eds.) Handbuch Kindheit, Ökologie und Nachhaktigkeit, Verlag Barbara Budrich: Opladen & Toronto. It is presented here in the original English and with minor modifications as a CUSP Working Paper to make it accessible to English-speaking readers. We are grateful to the Economic and Social Research Council (Grant No: ES/T014881/1 & ES/M010163/1) and to Laudes Foundation for financial support of this work.