BLOG

Amidst growing interest in deliberative citizens’ assemblies on climate change, the link between democracy and sustainability has become a hot topic. To protect both at a time of high political tension, we must refrain from treating democracy as a mere instrument employed from the top down, and instead advance genuine democratic renewal.

The horror of the last weeks and months are a compressed version of the last 30 years in bushfire and climate politics, CUSP researcher Marc Hudson writes, it needs radical changing. The public must stay informed and demand better from our elected representatives.

Our way of life must change if we want to avoid climate breakdown—but how much can we do as individuals? Ahead of the upcoming ICTA-UAB Conference on Low-Carbon Lifestyle Changes, Joël Foramitti, Lorraine Whitmarsh and Angela Druckman are outlining a roadmap.

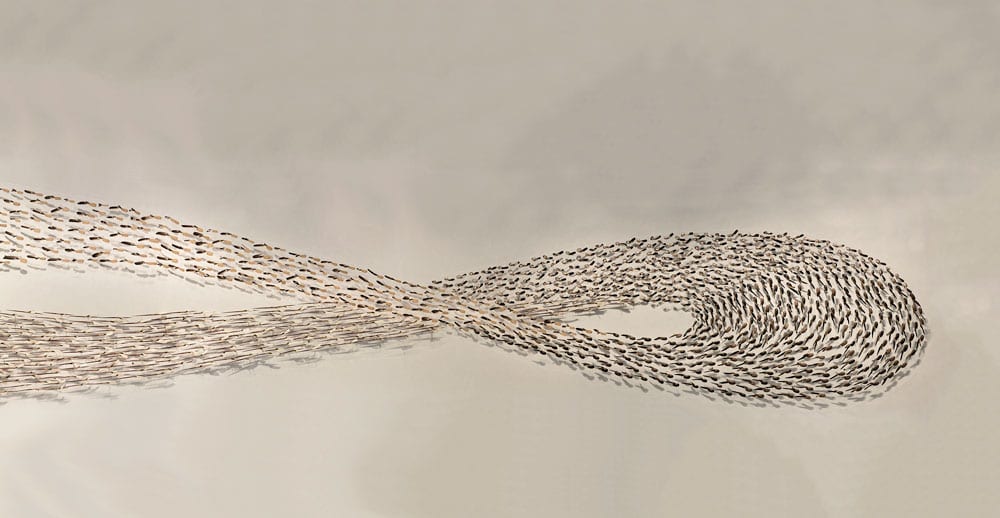

Our food, finance, and logistics systems are worryingly vulnerable to climate shocks, Aled Jones and Will Steffen write. These are not distant existential issues raised by uncertain and abstract models of future climatic risk. They are urgent questions that humanity has been ducking for decades, but now demand urgent answers.

Meaningful work does not have to be at the price of decent work conditions, research by our partners at Middlesex University finds. In this blog, Deputy Director Fergus Lyon is introducing a new project that will be further investigating the various economic tensions within community businesses; and is calling for case study partners.

It is clear that the larger the economy becomes, the more difficult it is to decouple that growth from its material impacts… This isn’t to suggest that decoupling itself is either unnecessary or impossible. On the contrary, decoupling well-being from material throughput is vital if societies are to deliver a more sustainable prosperity—for people and for the planet. (This article is posted on the Science website).

For Joseph Schumpeter, ‘creative destruction’ was an inherent feature of Capitalist development; what if we apply its logic to transformative political change instead? We have plenty of solutions at hand, Daniel Hausknost argues; it’s time for decisions.

To explore pathways to accelerate change, a group of sustainable businesses were brought together recently, exploring how Micro and Small enterprises can, and do already, disrupt the fashion sector. CUSP researcher Patrick Elf attended the project workshop, and here shares some of his reflections.

What will it take for us to save ourselves?—CUSP has supported the development of a theatre adaptation of The World We Made; and with support from local citizens groups and the ESRC is bringing it to venues across the UK. Jen Horn has attended one of the performances. These are some of her reflections.

To address the climate and ecological crises, we need a vision of the future. But some of the most popular ones out there will only propel the planet more quickly towards destruction, Joanna Boehnert and Simon Mair write.

Robert Shiller’s new book probes how social behaviour trumps statistics in determining the fate of economies—Tim Jackson weighs it up. (This article is posted on the Nature website).

Introducing mandatory requirements for businesses and investors to disclose climate risks and what they are doing about them is an essential part of achieving net zero emissions argues CUSP co-investigator Nick Molho.

Across the world, societies are obsessed with increasing economic growth. Like an addiction we can’t quit, we know that ‘GDP-fetishism’ is a myopic, damaging way to view human flourishing. Yet despite years of effort to go ‘Beyond GDP’, it is as dominant as ever. Why? And what can be done about it?

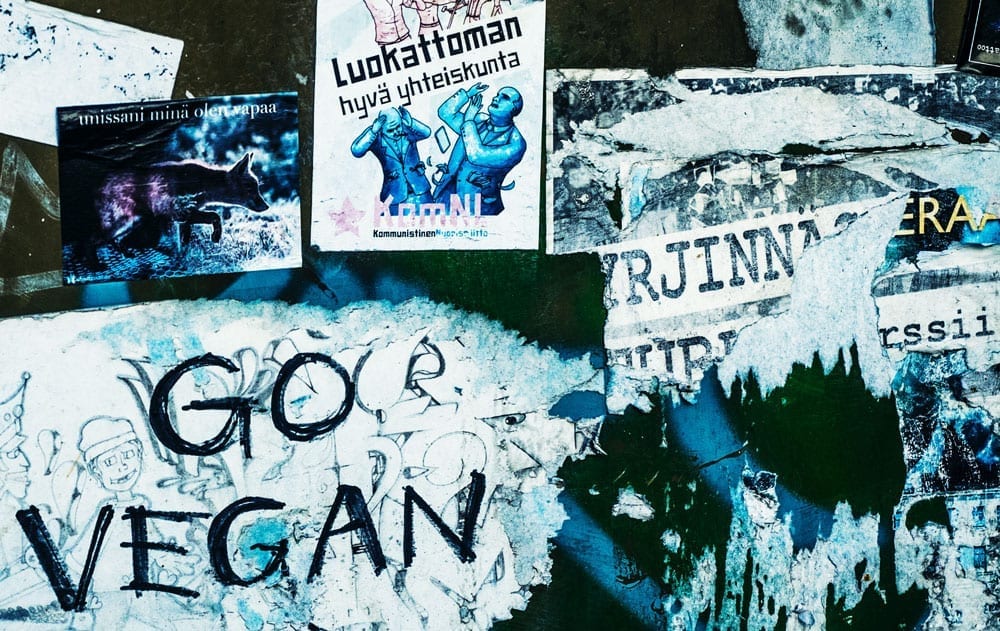

Environmental engagement is on television screens, in the streets and at your local book group; environmental communicators are everywhere and everyone.—A recent edition of the Environmental Scientist focuses on the new radicalism in environmental engagement. This blog was written for the Editorial.

Can we save the planet and still retain capitalism? Is transition to socialism the only way to end our addiction to unsustainable growth? Breakthroughs in economic theory may be suggesting a new answer to these questions, suggests CUSP researcher Richard Douglas: not capitalism or socialism—but both.

Much of the effort in the financial world in dealing with uncertainty is exerted in repackaging or ‘taming’ it as its more manageable relation, as risk. Yet, the power and politics that flow through technical models can have very adverse feedbacks in communities.

Gambling on a future of continued economic growth is a bad bet with long odds and extremely high stakes, CUSP researchers Ian Christie, Ben Gallant and Simon Mair write in this blog, outlining the basics of the ‘post-growth’ perspective.

Transforming our societies to stop climate change offers us the chance to make our lives better, Simon Mair writes. Let’s roll back specialisation and work on problems we think are important, that contribute to our communities rather than generating sales.

Right before the calendar moves into autumn, we hosted our third CUSP summer school, bringing together young researchers for three days to share ideas across the academic disciplines and experiences. In this short blog, Jo Kitchen shares a few reflections.

At current rates of reduction, the UK fair carbon budget will be spent in just four years’ time.”Every year that progress is delayed, the challenge only gets bigger”, he argues, we don’t only need a credible strategy on zero carbon targets, but also emission pathways, with a defined level of negative emission technologies.

If climate is becoming the latest battleground in the ‘culture wars’, should we just refuse to fight? Instead of facing off against massed armies in ranged battle driven by deep pockets, Lucy Stone argues, perhaps we should throw down our arms and look to see not just the white of each other’s eyes, but the person behind them.—A plea fo deliberative democracy.

As the consumerist understanding of what living well means is increasingly disputed for its unsustainability, the need emerges to look for alternative takes on the good life. In this blog, CUSP researcher Anastasia Loukianov presents an overview of her recent article with Kate Burningham and Tim Jackson, considering some of the understandings of the good life that can be found on Instagram.

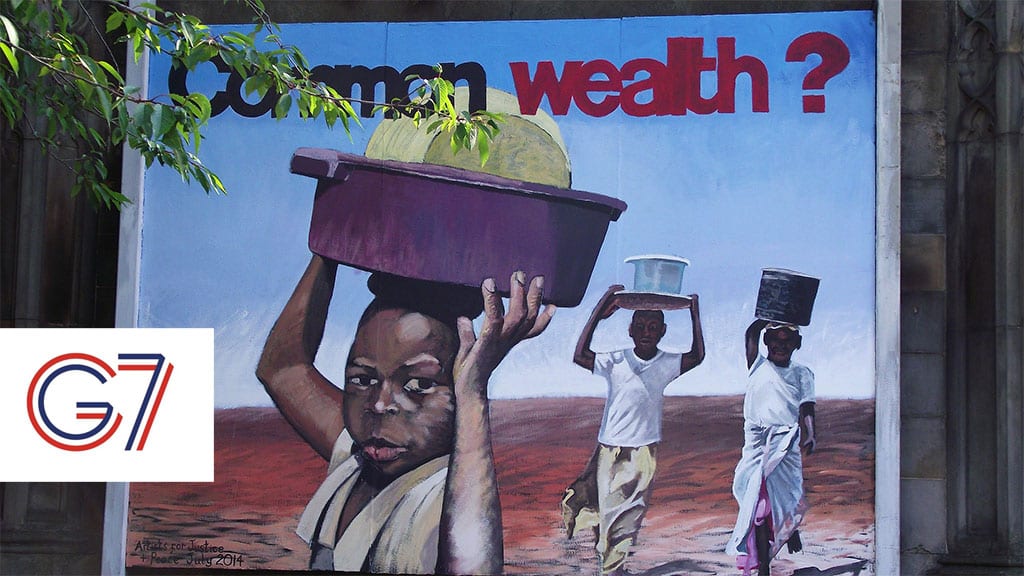

The gathering of world leaders in France this week offers an opportunity to address the existential issues of our time, Amanda Janoo writes in her guest blog—a more just and sustainable economy is not only possible, but a few strategic decisions away. (This blog first appeared on the Open Democracy website.)

Despite vast amounts of money being invested in Liverpool, the UK’s 2015 indices of multiple deprivation found the city to be the fourth most deprived local authority district in the country. Culture-led regeneration has been a central tenet of Liverpool’s economic ‘revival’ since the 1980s. Yet, the implementation of ‘creative cities’ policy has been contested in numerous ways—it’s not a one-size-fits-all strategy, Anthony Killlick’s case study shows. A summary.

The shortcomings of GDP have been widely recognised for several decades now, with a huge number and diversity of “alternative indicators of progress” being developed. In order to buy-in to a new indicator of progress, we don’t just need a new indicator. We need a new way of thinking about societal wellbeing that is grounded in sustainability and just distribution.

Climate change is increasingly being discussed as an existential threat to human civilisation. How should this affect the work of political scientists who are investigating environmental politics? CUSP researcher Richard McNeill Douglas offers this suggestion: by following Charles Taylor’s arguments for engaged social science.

“We owe future generations a better economy, not a bigger one”, Ben Gallant writes, recovering the concept of ‘usufruct’ for inter-generational politics. By focusing on growing the economy we forgot about all the other things that are handed down through the generations; not just the environment but cultures, communities and institutions as well. For many years now, we have consciously broken the terms of our ‘usufruct’—it’s high time we revisited the terms of the contract again.

Unexpected for Joanna Kitchen, her field work investigating socio-environmental accounting procedures in hybrid organisations led her to the ancient wisdom of First Nations communities, with thousands of years of unrecognised sustainable practices and innovation, and the relationship they hold with the land—it is undeniable, she finds, that having their voices heard can bring about new solutions to long-held challenges. But the concept of ‘inclusive growth’ may not be it.

‘Green growth’ is conventionally trusted to fix climate change—a highly risky strategy, Christine Corlet Walker argues, when the technology needed to decarbonise the economy is nowhere in sight. So why, if we can be so optimistic about humanity’s ability to develop fantastical new technologies to bend and overcome the limits of nature, can’t we lend that same optimism to developing new economic structures? (This blog first appeared on The Conversation.)

We are currently trapped between dysfunctional forms of populism and an increasingly defunct policy orthodoxy of market liberalism, Charles Seaford argues. But this is not inevitable. We need to reconstruct the moral foundation for politics, and build the alliances needed to give it political and practical expression.

In July 2019, the think-tank Policy Exchange put out a report that frames the Extinction Rebellion in terms of extremism with potential to terrorism, calling on government for forceful approaches to curb the XR movement. A worrying assessment that is far from being justified, Simon Mair and Julia Steinberger write in their defence of XR’s economic and political programme: Given the outlook of climate breakdown, what constitutes extremism, and who gets to decide this?

Climate emergency demands a wholescale shift away from fossil fuels. Tim Jackson and Andrew Jackson reflect here on the emerging concept of ‘transition risk’, a key element in the Bank of England’s response to climate change, and outline the challenges inherent in understanding and modelling it.

With every day that passes the climate crisis grows more urgent and the responsibility of scientists to intervene in policy grows. It’s a pressure, Ben Gallant describes his experience at the recent ESEE conference, that is changing identities and is creating tensions in the Ecological Economics research community.

‘System change, not climate change’ is the mantra for a new politically-charged ecological activism. In the wake of two key economic conferences, CUSP director Tim Jackson reflects on what this means for the financial and political stability of Europe.

The 15th Conference of the Parties in Copenhagen in 2009 was meant to launch an international framework that realigned our development trajectories towards a low carbon future. A decade later, with rising emissions, we still find a significant set of barriers to unlocking this low-carbon pathway to sustainable prosperity.

There are no silver bullets to the climate breakdown. Various scenarios offer a range of solutions to the same issue—all providing stories for a course of action sorely needed today. These opportunities can be put together to create alternatives to the prevailing business-as-usual approach. World Environment Day might have been a good conversation starter in the 1970s, the Agulhas Climate Hub write in this guest blog, but it needs a radical shakeup to get us where we need to be in time.