A fair days wage for a fair days work?—Why are wages unfair, and what can we do about it?

The clothes worn by most people in rich countries are made by people in poorer countries, who are getting very low wages. Most of us intuitively know that the wages received by the people who make our clothes are unfair. What’s harder is explaining why, and saying what we might do about it. Summarising his recent journal article with Tim Jackson and Angela Druckman, Simon Mair uses the living wage as a basis for claims about fairness, and discusses regional collective bargaining as a solution to unfair wages.

It certainly isn’t unusual for workers in poorer parts of the world to be paid very little. Recent studies have demonstrated the incredible extent to which rich economies rely on low wage labour in poorer countries. Likewise, we can definitely say that there are inequalities in global supply chains. But neither of these things necessarily tells us anything about fairness.

Indeed, in some frameworks very low wages can be considered fair. For example, ‘marginal productivity justice’ [PDF]] says that fair wages are those that are equal to the value you add through your work. You are being paid fairly when (in economic jargon) your marginal wage is equal to your marginal product. Low wages are fair because they reflect the low value that you’re bringing to production. Under this framework, we might argue that Western European workers earn more because they are worth more. In fact, paying workers in poorer countries the same as Western European workers would be unfair because the former haven’t earned it.

However, marginal productivity justice is rejected by most labour activists and also by many economists. This is partly because it relies on the assumption of a perfectly competitive labour market. In reality, labour markets behave so differently from the descriptions found in mainstream economics textbooks that prominent heterodox economists argue they “do not really exist”. More importantly, marginal productivity justice is often rejected because it lacks a basic humanity. Workers deserve to be treated as human beings, not commodities to be traded at the lowest possible cost. Marginal productivity justice ignores the inhumanity of wages so low that workers struggle to meet their basic needs.

The best known framework built around the idea that workers are people is the living wage. The living wage starts from a moral imperative: workers have a human right to a wage that provides a decent quality of life. In practice, the living wage is taken to mean that your wage should provide you and your family with financial security and sufficient resources to be able to partake in society. A wage that doesn’t provide this is unfair.

Our recent paper in the Journal of Life Cycle Assessment used the living wage concept to assess the fairness of wages in Western European clothing supply chain. To do this we estimated living wages for Brazilian, Russian, Indian and Chinese workers, working in the Western European clothing supply chain. Then we estimated how different their actual wages were from the living wage.

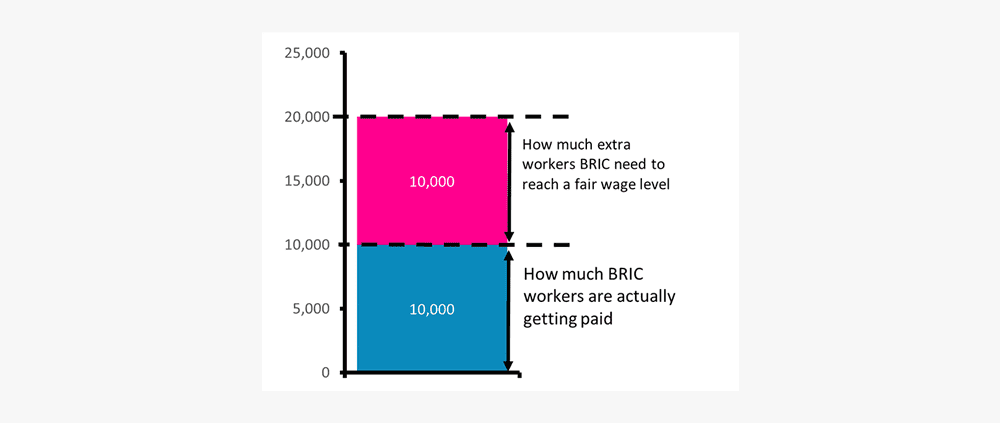

What this showed was that wages are extremely unfair. The total cost of BRIC labour in the Western European clothing supply chain is about half what we would expect to see if workers were being paid fairly:

Put another way, the average a worker in the BRIC countries working in the Western European clothing supply chain makes about half what they need to live a decent life.

Before we move to what we can do about this, it’s worth pointing out a wonkish but important methodological problem with looking at living wages in global supply chains: tax rates and social security contributions. These impact on how much pay workers actually take home, represent additional costs to employers and vary between countries. Yet, they aren’t accounted for in international studies of wage fairness. This is a major oversight because social security rates and taxes effect what you might want to do to try make wages fairer.

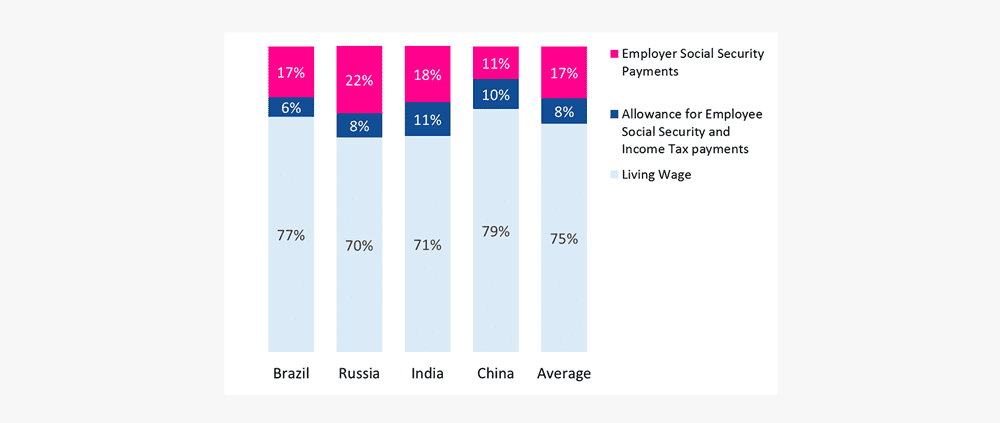

A wage that looks fair before tax might not be fair when you take out income tax and employee social security contributions. We found that including an allowance for taxes and social security contributions substantially changes the size of living wage estimates. We estimated that living wages in BRIC would need to be around 10% higher to ensure they were still fair when you take employee social security and taxes out of them.

When you look at the total cost of living wages from an employer’s perspective, the picture changes again. Employers are not so much interested in the wage as they are in the total cost of labour – labour compensation. Living labour compensation is what we call the total cost of labour assuming workers are taking home a living wage. Employer social security rates vary between countries. For a worker in China, only 11% of the total cost of that worker to an employer is employer social security contributions. On the other hand, in Russia 22 % of the labour cost to an employer is employer social security payments:

In short, because social security rates vary between countries even if Russia and China had the same after tax living wage, the total cost of labour to the employer would be different.

This variation in the total cost of labour (even assuming the actual wage is constant) can be good or bad. It means you can have a living wage and still have competition based on labour costs. If you think this is essential to economic development and market functioning, this is good. If you want to prevent a race to the bottom (even a ‘fair’ bottom), it is bad.

This brings us to what we could do about the situation. Generally a race to the bottom is a bad thing, and is part of the reason we end up with unfair wages in the first place.

One option to stop a race to the bottom is regional collective bargaining. This is currently being pursued by the Asia Floor Wage Alliance – a collection of NGOs and trade unions. Their aim is to establish a wage floor common to all the Asian countries that allows workers to live well and stops firms racing to the bottom. Our results show that this kind of regional collective bargaining strategy must be based on the total cost of labour from the perspective of a firm – living labour compensation.

If regional collective bargaining is based on the living wage, not living labour compensation one of two things will happen. Either the take home wage of each worker risks being unfair – because their tax payments mean they will take home less than the living wage. Or, if the floor wage is after tax, then firms might compete on the basis of labour taxes. Instead to moving to wherever the cheapest wages are, they might move to the country with the lowest social security contributions. This would encourage countries to reduce social protections. In short it would just shift the focus of the race to the bottom, and not challenge the underlying logic in the way that regional collective bargaining intends.

Back to the issues we started with, then. Wages in the Western European clothing supply chain are unfair. Why? Because many workers don’t earn nearly enough live a decent life. What can we do about it? One option is regional collective bargaining. This strategy can prevent companies from racing to the bottom on wages. But it has to be done on the basis of living labour compensation rather than living wages so that workers social protections remain in place.

Links

- The full paper can be accessed on the Springer website (open access).

- Chasing good work – Simon Mair’s and Agni Dikaiou’s reflections on The Taylor Review