The invisible heart: postgrowth economy as care

Care is an anathema to capitalism. Its virtues are capitalism’s vices. Its employment-rich foundation for wellbeing is capitalism’s ‘productivity crisis’. Yet, without care we are nothing, our progress is nothing. Without care there is no economy. A talk delivered by Tim Jackson at the #BeyondGrowth conference at the European Parliament, Brussels 15 May 2023.

By Tim Jackson

Thank you for inviting me here, in particular to this session. For me, the care economy is more than just a side panel in the ‘beyond growth’ debate. It is the blueprint for a post growth economy. Let me try to explain why—with a very simple question.

What can prosperity possibly mean on a finite planet?

This question has been the guide for our work at the Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity for more than a decade.

The conventional answer of course is that prosperity is about wealth and in particular about accumulating wealth, about having more.

And when you don’t have enough to survive, when the harvest has failed again, the sanitation is non-existent, the house is falling down, the well has run dry or become polluted, then having more—having anything—makes a lot of sense.

But what next? When do the ‘fairytales of eternal economic growth’ as Greta Thunberg has called them stop being a reliable formula for wellbeing and become a recipe for disaster? What is prosperity, when the climate changes, nature reels and human lives become cluttered and meaningless?

When you ask people, as we did when I was economics commissioner at the Sustainable Development Commission, you find, fascinatingly, that ‘health’ is what comes out at or near the top of most people’s lists. Our own health. The health of our families. The health of our communities. The health of the environment.

What would happen if we thought of prosperity systematically as health—rather than as wealth?—where health is conceived, as the World Health Organisation has defined it, as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing—and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’.

What difference would this make?

Well perhaps first, in place of ‘always more’ we might be tempted to think more deeply about the concept of ‘enough’. To return to what Aristotle described as the ‘virtuous’ balance between deficiency and excess—where the word virtuous is meant here in the sense of virtuosity, or skill or perfection as much as it is about moral virtue.

Capitalism’s fundamental conceit—one of its many conceits—is that, in striving relentlessly for ‘more’, it has no way of knowing where ‘enough’ might lie. Or how to stop when it gets there.

Take something really simple—something vital to human life—like breath. We don’t survive without sufficient air. But we don’t do well either by hyperventilating. It’s entirely possible to breath too much, or too fast, or too shallow. The connection between breath and life is complex and profound. It’s about balance rather than more. There is no in-breath without the out-breath.

A slow in-breath followed by a long out-breath, with the air on the out-breath slightly compressed by the throat is known to stimulate the vagus nerve and induce what is called a parasympathetic state in animal bodies—a calm, relaxed, state of wellbeing.

By contrast, the heady rush towards more and more, the relentless terror of status competition, the never ending acquisitiveness of consumer society stimulates the fight or flight response. A continual state of heightened anxiety.

Or let’s take nutrition. When you’re forced to the food bank, just to survive, as many care workers still are today. Then having more is a no-brainer. But today across the world, according to the WHO, more people die from diseases of over-consumption (obesity, hypertension, diabetes) than die of malnutrition. It’s an extraordinary indictment of the profit maximisation within fast food chains and the philosophy of more that legitimates them.

So what? you ask. What’s that all got to do with the care economy?

Well first, it’s clear that care is not just cure. It’s not about selling more and more pharmaceuticals. It’s not just the patient nursing to health of the sick. The bringing up of our children. The solace we can bring to the elderly, the infirm, the dying. It is all those things of course. But it is more. It’s about the way we live our lives. How we organise our societies. How we run our economies.

Care is something that can meaningfully be taken as a quality of the economy itself. At least. It can—when it is. In our economies it isn’t.

The US sociologist Joan Tronto suggested something similar when she defined care as an activity ‘that includes everything we do to maintain, continue or repair our “world” so that we can live in it as well as possible’.

Maintain, continue, repair, nurture, nourish. Care in its essence is characterised by the need to pay attention to people, to things, to the planet itself.

Most obviously, the attention of one human being to another lies at what Nancy Folbre called the ‘invisible heart’ of the economy. While Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ is busy insisting that we are all self-interested producers and consumers, Folbre points out that without care we are nothing. Our societies are nothing. Our progress is nothing. Without care there is no economy. Not even at the most basic level.

Care continually improves the quality of our lives. But more than that, it involves human beings in the service of each other and of the material world. And so it has the potential to provide society with a never-ending source of employment.

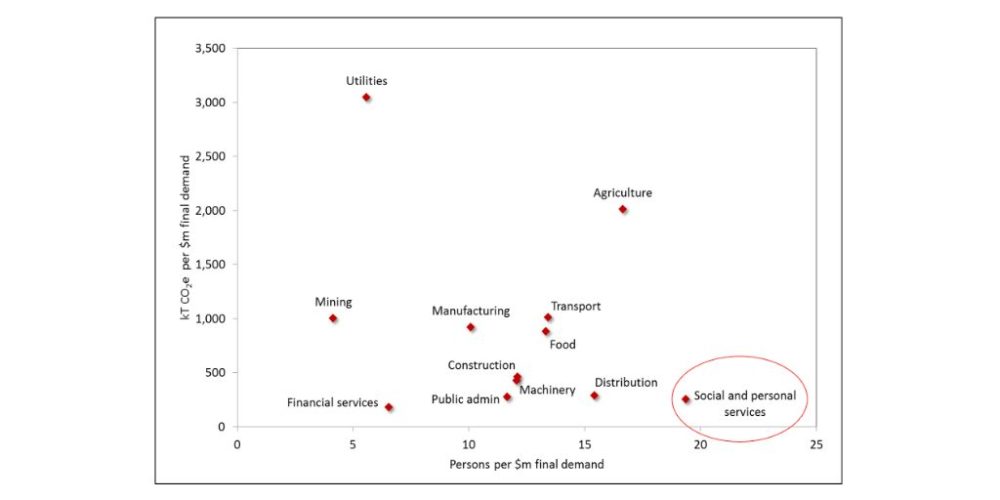

Even in the formal economy, as this Figure shows, the social and personal services—a sector where many care activities live—has the highest employment intensity in the economy.

There’s something else remarkable about this Figure. The horizontal axis shows employment intensity. The vertical axis shows carbon intensity. The care sector has a considerably lower carbon footprint than the materialistic, consumer economy that provides the foundation for modern economic growth.

We’re looking at an ‘economic sweet spot’ a place which offers a blueprint for a wellbeing economy. An economy that works for people and planet. An economy whose vision of progress is health—not wealth.

There’s just one problem with it. And it begins with ‘c’: capitalism.

Care is an anathema to capitalism. Its virtues are capitalism’s vices. Its employment rich foundation for wellbeing, is capitalism’s ‘productivity crisis’. To the mainstream economist, employment intensity translates as low or stagnant productivity growth. The thing that’s ‘holding us back’ from the growth we are so obsessed with.

And things get worse.

In the so-called social contract of neoliberal economics, wages follow productivity growth. So capitalism condemns care workers to pitiful wages, insecure jobs, impossible working conditions and—pandemic aside—the lowest ranks in the status game played out in modern society. Forgetting that without care we are nothing.

Of course, you don’t need me to tell you that most of the people working in the care sector (paid and unpaid) are women. You don’t need me to tell you that measuring productivity in monetary terms, as Commissioner von der Leyen reminded us this morning, measures ‘everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile’. Valuing only what can be produced and consumed at cost to the planet misses the foundation for life itself.

You don’t need me to tell you that the game of productivity is rigged. Rigged in favour of men. Possibly. Rigged in favour of what the late Herman Daly called uneconomic growth. Probably. Rigged in favour of those who profit from distress and ecological devastation. Definitely.

Which is why this session matters. Not peripherally to the Beyond Growth conference, but as the living beating heart of its concerns.

The care of human life—and not its destruction—is the first and only task of government, wrote Thomas Jefferson at the beginning of the nineteenth Century.

And so our job in rescuing the care economy is not just to applaud the nurses from our doorsteps, or support their strikes for decent pay. It’s not just to rail against patriarchal system—though that of course is one of greatest joys of attending a session on the care economy.

Our job is to reconceive economy as care. To equalise the horrendous health inequalities that condemn so many to unhappy unhealthy lives. To build some concept of universal basic services. To protect the rights, wages and living conditions of care workers. To reform the distorted productivity that robs care of meaning. To constrain the rent-seeking behaviour of private firms intent on extracting value from people’s infirmity. To reframe primary health care as a lifelong strategy of positive health.

Our job is nothing less than to unravel the systematic distortions of value that lie at the core of a broken capitalism. And to begin to construct an economy of care, craft and creativity fit for purpose on a finite planet. And. Oh yes. To paraphrase the infinitely more articulate Taylor Swift: to bring down the patriarchy.